Virginia Pinelands Flowers in bloom at Virginia's Piney Grove Preserve. The open pine savanna habitat is a hotbed for biodiversity. © Robert B. Clontz

Before I arrived in Virginia this summer, the concept of a pine savanna was completely foreign to me. I grew up in the conifer forests of the Cascades region, and my only point of reference for pine ecosystems had been the red and white pine forests surrounding Lake Michigan that I would see when visiting my grandparents.

That pine could grow in the South simply wasn’t a thought that had crossed my mind. But it does. That fact should be obvious. The extensive longleaf pine ecosystem once covered the Atlantic and Gulf coastal plains, stretching from Virginia down to the Florida Panhandle and extending west to Texas.

These pinelands should be the characteristic ecosystem one thinks of when they imagine the Southeast. Yet, today, longleaf pine occupies less than 5% of its original 92-million-acre range.

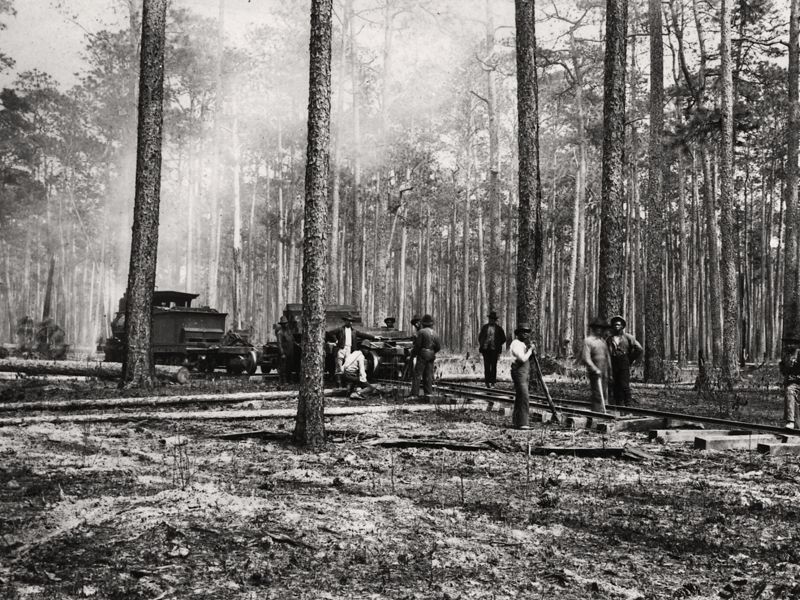

Virginia has one of the most extreme stories of loss when it comes to pine forests. When English settlers arrived in 1607, more than 1 million acres of longleaf-dominant forest stretched south from the James River. Adapted to fire and resistant to drought, wind and pests, the longleaf pine has served for centuries as valuable habitat. But settlers found value in the pines by cutting them down, constructing ships from their trunks and deriving tar and turpentine from their sap.

By the turn of the 21st century, only 200 mature trees remained.

I turned these facts over and over in my mind on the drive from Charlottesville to Wakefield. Located about an hour southeast of Richmond, Wakefield has been home to The Nature Conservancy’s Piney Grove Preserve for 25 years. Today, Piney Grove protects 4,000 acres of the historic longleaf pine belt. However, the preserve itself contains little longleaf pine—this site, too, fell victim to longleaf deforestation. Now, the forest is dominated by loblolly and shortleaf pine. But through the efforts of TNC and its partners, longleaf is returning to the forest, slowly but surely.

Quote

I couldn’t shake the feeling of my own humanness. It might sound strange, but being surrounded by a landscape so specific in its design and functionality was humbling.

Along with Eli, my roommate and fellow intern, I had picked a Tuesday to trade office work for this chance to enjoy the product of our work with TNC: protected lands. Neither of us being Virginia natives, we found the scenery novel and captivating. We passed through Petersburg, a town where saplings shot up from sidewalk cracks and threatened to colonize resident’s homes. Further east, we began to see signs advertising “VIRGINIA’S OLDEST PEANUTS.” Later, we would give in and pull over to buy some.

After about two hours, highways then dirt roads—with a couple of wrong turns—we were there. It was a hot July day, and, as we had traveled from the Piedmont to the Coastal Plain, it was only getting hotter. As we started down the Darden Trail, I thought, uncritically, that this forest didn’t look much like the pinelands I’d seen in pictures. A dense collection of mixed-species trees and shrubs didn’t strike me as anything special. Then we passed the fire line.

Prometheus Gives Fire to the Southeast

If there’s one thing about living in Virginia that took me off guard, it was the constant cycle of storms. At first, when dark clouds began to roll over the sky, I would get worried and hole up indoors. Although the Pacific Northwest faces an almost constant drizzle, I’d take that any day over the tempestuous weather of the Southeast. But now I’ve begun to appreciate, even enjoy, Virginia’s stormy nights.

Where lightning strikes, fires burn. For species endemic to the Southeast, the presence of fire presented an evolutionary challenge: adapt or die. So they adapted.

The presence of fire causes longleaf to grow in a unique way. For the first two years of its life, a longleaf pine wouldn’t even be recognizable as a tree to most people. Rather, its long tufts of needles make it appear to be a grass. During this grass stage, longleaf survives fires by protecting its terminal buds within a covering of needles. When it’s ready to grow, it does so suddenly: The tree shoots up quickly—at a rate of one to two feet per year—to achieve a stature largely impenetrable by fire.

Quote: Bobby Clontz

The worst thing you can do to longleaf is plant it and not burn it.

The longleaf uses fire to its advantage. Routine burns eliminate fungus and bacteria, which might otherwise threaten the health of the trees, and they take out competing plants, especially hardwoods that can’t endure the high temperatures.

The fire line we crossed couldn’t have been more obvious. On one side lay a dense, mixed-species forest. On the other, a spacious grove of pines. At their bases, scorched bark revealed where fires had attempted to climb. Though clearly marked by fire, these trees were not damaged.

Fuel for fires covers the ground in these pine forests. As we walked the trail, at our feet lay dry pine needles, cones and thick clumps of grasses and shrubs. It seemed that just a spark could start a low-intensity fire that could burn quickly through the area.

Eli called out for my attention. A dense stand of young pine was visible a hundred or so feet off the trail. Half singed, the young pines were engaged in a life-or-death competition. In a year or two, only the strongest will remain, and this patch of pine will be as evenly spaced as the rest of the forest.

As I let the sunlight coming through the canopy soak into my skin, I wondered how early settlers of the Southeast could have ever cleared these forests. That’s always the question with conservation—modern people wondering how those who lived before us could’ve been so foolish as to let ecologically and culturally important species face extinction.

The story of pine forests in Virginia will sound familiar to those versed in conservation history. Much like the American bison or passenger pigeon, the longleaf story is one of putting profit over nature, of lack of education, of mistakes and coincidence. It’s both wildly complex, and, in hindsight, shockingly simple. But most Americans, even most Southerners, remain unaware of this history.

Turning our Backs on Fire

Since many scientists estimate that these longleaf pine forests have only been around for the last 5,000 years, Indigenous presence in America predates the ecosystem by at least 10,000 years. Thus, there is no longleaf forest without human influence.

While the Native cultures endemic to the Southeast didn’t live in the pine savannas, these ecosystems were integral to their livelihoods. They burned resin-filled longleaf for heat, for cooking and for torches used during hunting and fishing expeditions. They used the strong heartwood to pave paths and build houses.

To maintain the pine forests, Indigenous people would ignite fires, usually in the fall or winter. These fires encouraged the growth of the pinelands, allowing them to flourish and sustain the people and place.

Quote

The pine will keep rising from the ashes. And, hopefully, the tide will turn. After all, humans were always a part of the longleaf ecosystem. With the right actions, we can intertwine our destinies once more.

Virginia, being the first landing place for English colonists, lost these Indigenous stewards relatively early. Disease and genocide largely forced the Indigenous (those who survived) from their land. Still, some settlers conducted infrequent burns to clear land for travel or for raising hogs.

After finding that the resinous pine could be converted into tar, pitch and turpentine, European settlers soon began cutting down pine all along the East Coast. Beginning in New England, loggers went southbound from forest to forest, clear cutting, processing and exporting these products. By the time they made their way to the Southern colonies in the mid 1700s, the naval stores industry was in its heyday, and Britain was ready to pay a pretty penny for prime seafaring materials.

Gradually, as Indigenous knowledge was lost, a fear of fire began to take over American culture. Fire suppression policies began popping up around the country and were cemented as the norm after the Great Fire of 1910. This massive wildfire had terrorized the Northwest.

For longleaf pine forests, the era of fire suppression meant the end of their regeneration. Both leaf litter and the canopy cover from hardwoods prevent longleaf seeds from germinating. Even if longleaf is planted, it won’t grow without exposure to direct sunlight.

“The worst thing you can do to longleaf is plant it and not burn it,” says Bobby Clontz, TNC’s stewardship manager for Southeastern Virginia. After visiting the preserve, I had called Bobby to discuss the current and historical management of Piney Grove.

TNC and myriad partners have brought controlled burns back to the region. Even Smokey Bear has changed his tune. Now, Piney Grove receives good fire every two to four years, facilitating the planting of longleaf and the overall success of the ecosystem.

Longleaf the Phoenix

There’s a profound beauty in a species like longleaf pine. Not only does it thrive, as most pines do, in sandy, nutrient-poor soil, but it also withstands the weather patterns of the American Southeast.

Being used to the diverse forests of the Pacific Northwest, I’ll admit that seeing the dominance of a single species shocked me. But truthfully, there’s much more to the pinelands ecosystem than meets the eye.

Because the longleaf ecosystem is entirely different from the hardwood, spruce-fir or oak-hickory forests found elsewhere in the American Southeast, it is also home to a unique collection of specialist species. Over 120 species of concern live within the pinelands, making it a priority for conservationists. It has an incredible wealth of plant biodiversity; more than 40 plant species have been documented in a single square meter.

Within these quiet open forests, bird calls come through clearly, facing only the competition from the wind blowing through the treetops. While I was kicking myself during our hike for having forgotten my binoculars, Eli began recording and identifying the cacophony of conversations above us. Eastern wood-peewee. Northern cardinal. Tufted titmouse. With bated breath, I waited for “red-cockaded woodpecker” to appear on the screen, but, in hindsight, I was too hopeful.

Of all the species endemic to longleaf pine forests, the red-cockaded woodpecker receives the most attention. A keystone species, the woodpecker creates tree cavities that are used by a whopping 27 other species. At their historic lows, there were only two breeding pairs left in Virginia. Now, thanks to conservation efforts, over 100 birds are thriving in the state.

It’s a miracle they remain in the state at all. According to Clontz, a chance wildfire in 1943—a time when fire suppression was in full swing and longleaf had been reduced to 1/6 of its original range—was most likely the single event that allowed the pine forest ecosystem to survive until TNC reintroduced fire in 1999.

We walked on, finally arriving at a wooden observation deck at the end of the path. Peering out over the edge, I couldn’t shake the feeling of my own humanness. It might sound strange, but being surrounded by a landscape so specific in its design and functionality was humbling. From this vantage point, Piney Grove seemed endless—I could imagine spending days walking further and further into the open forest, encountering and conversing with the residents: fox squirrel, bobwhite quail and elusive red-cockaded woodpecker A whole community of animals is bound to these lands, having adapted to fill the niches created by these unique forces.

In her memoir about growing up in longleaf country, Ecology of a Cracker Childhood, Janisse Ray writes that “the land itself has been the victim of social dilemmas—racial injustice, lack of education, and dire poverty.”

Standing on the observation deck, I took note of myself as a visitor. Soon I will leave Virginia and unentangle myself, at least for the time being, from its landscapes and stories. But all of this will stay. The pine will keep rising from the ashes. And, hopefully, the tide will turn. After all, humans were always a part of the longleaf ecosystem. With the right actions, we can intertwine our destinies once more.

About the Author

Susan McHarris was the summer 2023 communications intern for TNC’s Virginia Lands and Lives Project, exploring stories of under-represented communities through the lenses of conservation and environmental justice. She is also the author of “Accepting a Queer Nature: How queer ecology can make us better conservationists.” From Portland, Oregon, Susan is a philosophy and environmental studies student at Swarthmore College.

Get More Nature News

Get the best nature stories and news from Virginia delivered monthly. Get a preview of Virginia’s Nature News email.