Considering the current state and importance of Latin America, our strategy focuses on the transformation of agricultural landscapes.

Regenerative agricultural systems seek to improve the natural conditions while ensuring water and food supply for the population, generating benefits such as greater climate resilience of ecosystems, an increase and greater conservation of biodiversity and natural resources and higher productivity.

Discover how our strategy works

Why do we work here?

In Latin America, we want to create a sustainable future for our planet through regenerative production systems, where nature and science come together. This important region features:

-

16%

of the Earth’s Surface

-

25%

of the world’s forests

-

25%

of global exports (agricultural and fish products)

-

30%

of the planet’s freshwater

-

40%

of the world’s biodiversity

Together with partners and donors, we seek to face current agricultural challenges, protecting ecosystems, regenerating their resources and building resilience.

Latin America is one of the most important regions globally in terms of food security. Learn how we transform production systems in this region:

Why R2A?

Today’s agricultural and ranching production systems, seeking to expand and have outstanding yields, consume 70% of freshwater and cause 70% of habitat conversion in Latin America.

Current farming and ranching practices consume 70% of freshwater resources and cause 70% of habitat conversion in the region. Nearly half of Latin America’s total land surface has some level of degradation, and deforestation is now three times the global rate, making agriculture the leading contributor to gas emissions in Latin America. Conventional agricultural practices, seeking to expand and increase their yield, have damaged the natural capital on which the agricultural success of the region depends, jeopardizing its exceptional potential to continue to contribute to global food production.

Sustainable and scalable solutions

- Scaled design - shift from local successes to broader regional systems.

- Avoid unintended consequences - stay focused on long-term profits, not just quick solutions.

- Appropriate feedback loops - Avoid turning yesterday’s solutions into tomorrow’s problems.

- Avoid turning yesterday’s solutions into tomorrow’s problems - focus on drivers to accelerate solutions.

THROUGH NATURE:

- Ecological systems and processes are maintained and restored throughout the region.

- Biodiversity is restored and protected in agricultural landscapes. Avoid unintended consequences – keep the focus on long-term profits, not just quick solutions. Correct feedback cycles – avoid turning yesterday’s solutions into tomorrow’s problems.

For agriculture:

- Yields increase with fewer inputs, generating healthier soils, using less water and benefiting ecosystem services. Producers endure climate change shocks and market fluctuations.

Agricultural businesses transition from being product suppliers to being service providers with shared benefits in environmental and social terms.

People:

People:

- Rural communities improve livelihoods through cleaner water, stable income, resilient production systems and better access to markets.

Strategy

Our strategy is committed to improving production systems and ecosystem services in the Latin American region.

Through this, we aim to generate resilience and socio-economic development, better ecosystem conditions, greater carbon sequestration in the soil and greater stability and resilience for agricultural productivity and value chains, through a systemic and comprehensive effort based on natural climate solutions.

With our strategy, we work to implement regenerative ranching and agriculture practices to restore production areas in Latin America.

Our projects demonstrate the importance of scaling impacts that drive transformation in markets, productivity, environmental, social and economic conditions.

Considering the principles of our strategy and synergistic interventions, we seek to implement regenerative practices to create positive impacts on nature, the agricultural sector and people.

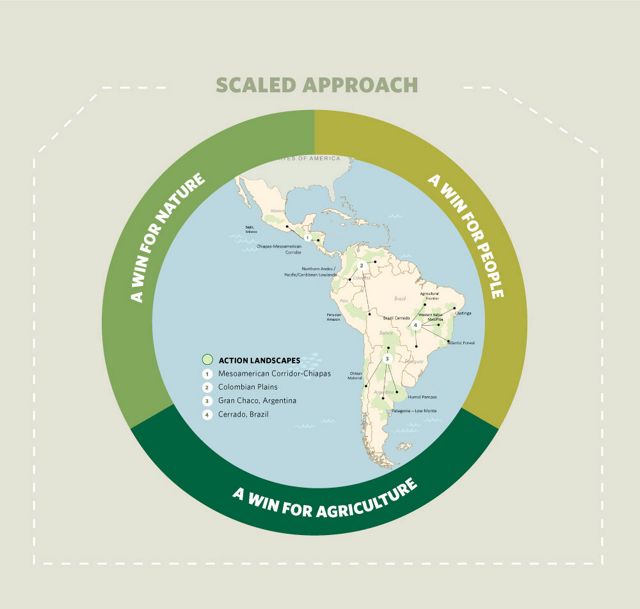

We aim to scale these impacts and ensure they last in the long-term. That’s why we focus interventions on action landscapes: implementing, evaluating and generating successful cases alongside key partners, to replicate these projects and contribute to the transformation of the agricultural sector and ecosystems in Latin America.

In addition, our strategy is supported by the Ecosystem-based Adaptation criterion, helping communities and individuals adapt and cope with climate change, motivating the sustainable use of ecosystem resources that are restored and preserved, and supporting equitable governance through multi-level policy support.

Goals of our strategy

Today, our strategy has achieved 45% of its 5-year impact targets across 7 action landscapes:

-

5,100 hectares

of agricultural areas with improved productivity

-

2.1 million hectares

of agricultural areas with improved management

-

0.55 GT eCO2 / 10 years

GHG mitigation (reduced emissions or increased sequestration)

Projection of our strategy

R2A operation and expansion: A regional proposal is designed to expand our strategy across 6 action landscapes and over 3 million hectares, considering current global experiences, prototypes and conditions.

Full scale of R2A: Raising awareness of the connection between agriculture and nature through R2A interventions and platforms with producers, companies, governments, associations and others.

About us

The R2A strategy was consolidated in 2016 to work collaboratively with partners and key stakeholders in the development of synergistic interventions that achieve market transformations, considering the agriculture sector´s rules, business models and environmental regulations, through the continuous improvement of regenerative ranching and agriculture, reducing the impact on nature and strengthening the well-being of humans and communities.

Our Partners

WHAT IS THE OPPORTUNITY FOR TRANSFORMATION WITH R2A?

Latin America is a key region for food conservation and security worldwide, but conventional production systems affect the natural resources it depends on. We hope Latin America improves the health of its resources and ensures current food demands, generating benefits for people, nature, and the agricultural sector.

Scalability is key to achieving our goal of transforming productive farming systems in Latin America, with nature-based solutions and regenerative practices that are resilient to climate change.

In Colombia, the GCS project, of which TNC is a partner, broadly applies principles of regenerative ranching and agroecology, transforming more than 42 thousand hectares of land into diverse forest-pasture systems.

In Argentina’s Gran Chaco region, TNC, along with partners and local allies protects nearly 500 thousand hectares of land through a collaboration platform, minimizing the loss of habitats and deforested areas to agriculture and ranching in the region.

Our Team

-

Mauricio Castro Schmitz

Director of the Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture (R2A) Strategy for Latin America View bio

-

Pilar Lozano

Deputy and Science Lead for the Ecosystem Based Adaptation (EbA) program within the Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture (R2A) strategy for Latin America View bio

-

Alicia Calle

Advisor for the Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture (R2A) strategy for Latin America View bio

-

-

Paula Casadei

Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist of the Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture (R2A) strategy for Latin America View bio

-

Valentina Joya

Junior Conservation Associate of the Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture (R2A) strategy for Latin America View bio

-

Julieta Clemente Mignone

Technical Analyst of the Ecosystem Based Adaptation (EbA) program within the Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture (R2A) strategy for Latin America View bio

-

Angélica Polanco

Operations Specialist for the Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture (R2A) Program for Latin America View bio

-

-

-

-

Alejandro Hernández

Program Manager Chiapas Program Mexico and North Central America (MNCA) View bio

-

-

-

-

-

-

Here are some examples of how R2A seeks to transform today’s production systems in Latin America

With long-term and large-scale impacts

Growing global agricultural demand in the context of climate change will increase the challenges this sector presents in Latin America.

For this reason, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), under the R2A strategy, promotes science-based practices, methods, and policies that increase agricultural productivity and protect environmental resources and services, generating more productive agricultural systems with increased resilience to climate change.

Why action landscapes?

Action landscapes in Latin America were determined from a spatial analysis conducted between 2017 and 2018 by a consortium of scientific institutions, which indicated the areas with the greatest potential for the strategy´s implementation and a greater impact on nature, the agricultural sector and individuals.

The action landscapes were selected under the following criteria: areas where the greatest yield and production efficiency can be achieved at present and in a climate change landscape in 2030; identifying land degraded by crop management and grazing; establishing landscapes where restoration can improve agricultural production.

Story Map

TNC believes in agriculture as part of the solution. R2A proposes to improve production systems by protecting and regenerating ecosystem resources.

Field Work

Colombia

In the Colombian plains, we implemented forest-pasture systems and sustainable practices at landscape level

Argentina

For the soybean production system, we promote the adoption of best practices to regenerate soil health

Brazil

In the states of Maranhão, Mato Grosso and Goiás we promote the integration of large-scale forest-pasture systems

Mesoamerican Corridor

In Chiapas, we developed agroforestry practices and forest-pasture systems, improving productivity at the farm level

Colombia´s Sustainable Ranching

Sustainable ranching motivates conservation

Quote: Blanca Raquel

There is not a single human being who does not need us farmers

Blanca Raquel

Chair of Asogranja, in San Martin, MetaQuote: Mercedes Murillo

I have received payments for live fences, forest and scattered trees, I am a very happy sustainable rancher

Mercedes Murillo

Beneficiary of the Sustainable Colombian Livestock project

Quote: Roxana Adames

The weather has changed a lot, so trees have to be planted in order to retain more moisture in the soil and provide more shade

Roxana Adames

Livestock farmer, San Martín, MetaTerms of Reference

-

Consultancy

Para la planeación, recolección y seguimiento de la fase de factibilidad para proyecto de carbono con sistemas silvopastoriles en el departamento del Cesar

DOWNLOAD -

Consultancy

Development of diagnostic studies for the implementation of EbA practices in regenerative agricultural systems in Peru

DOWNLOAD -

Consultancy

Analysis of variation in mammals and birds in farming systems in the Chaco region

DOWNLOAD -

Consultancy

Consultancy for the initiation phase of the Collaborative Alliance for Regenerative Agriculture in the Argentine Gran Chaco

DOWNLOAD -

Consultancy

Characterization of regenerative models in the Gran Chaco Food Landscape using ecosystem services analysis.

DOWNLOAD

R2A projects its efforts with a basis on science, identifying in a timely manner the needs for improvement in each Latin American region.

This allows us to make better decisions and ensure our purpose to generate scalable and lasting impacts over time. You can read more about the projects we carry out in Latin America and our achievements.

R2A materials

-

-

Regenerative Practices

Sugarcane farming

From a comparison between conventional and regenerative productive practices, we can achieve significant environmental impacts, especially increasing carbon sequestration in the Cauca Valley, Colombia.

DOWNLOAD -

The R2A strategy

Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture

Learn how we work on R2A, our theory of change and how we apply our strategic framework to achieve comprehensive and synergistic work. Learn about our projects and the results achieved within LAR with our scalable approach.

DOWNLOAD -

Description of our R2A strategy

Learn how regenerative ranching and agriculture in Latin America can protect nature and ensure the planet’s food security, generating sustainable solutions for nature, agriculture and people.

DOWNLOAD -

Our Action Landscapes in Latin America

Storymap

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) believes that agriculture can be part of the solution, and our goal in R2A is to promote practices, methods and policies that increase agricultural productivity while improving ecosystem resources

DOWNLOAD -

The R2A strategy, our principles

Interactive Infographic

In R2A, together with synergistic interventions and comprehensive work to improve agricultural productivity and ecosystem resources in Latin America, principles such as shared responsibility and continuous improvement help us stay on track to achieve impacts at a larger scale.

DOWNLOAD

Other resources

R2A and water funds in the Cauca Valley:

Learn about the positive impacts of the potential integration of these strategies by The Nature Conservancy • FDA and R2A in the Valley (infographic)

Agroindustrial sugarcane production in the Cauca Valley

Learn about the crop production methods in this region and their potential impacts under regenerative production practices • Sustainable sugarcane prouction in the Cauca Valley, Colombia (two-pager)

R2A in the field: Chiapas (Mexico)

R2A in the field: Brasil

Learn how the R2A strategy is implemented in the field for sustainable livestock production • (infographic)

R2A in the field: Argentina

Learn how the R2A strategy is implemented in the field for large-scale soy production • (infographic)

R2A in the field: Colombia

Learn how the R2A strategy is implemented in the field for the sustainable ranching sector • (infographic)

The Action Landscapes of the R2A Strategy

Read the full study for the selection of Action Landscapes in Latin America towards the implementation of our strategy. • Action Landscapes for Advancing The Nature Conservancy’s Healthy Agricultural Systems Strategy in Latin America

Landscapes Action Brief

Healthy Agricultural Systems Latin America Action Landscapes. • (English)

Regenerative Agriculture Brief

Regenerative Ranching and Agriculture Practices • (Spanish)

Healthy Soils

Chiapas • (Infographic)

MBGI and EbA

Argentina • (Infographic)

Soil Incineration

Chiapas • (Infographic)

Soil Recovery - Corn Farming

Chiapas • (Infographic)