Natural Climate Solutions

Natural climate solutions offer immediate and cost-effective ways to tackle the climate crisis—while also supporting healthy, thriving communities and ecosystems.

Colombia is home to 43% of the world’s paramos, a critical ecoystem that supports people, provides clean water and can help fight climate change.

“Unlocking Paramo: Protection and Restoration in the Highlands” summarizes research carried out by the TNC Colombia team to estimate the potential for paramo ecosystems to help mitigate climate change.

Paramos are a rare and unique ecosystem that they only exist in five countries: Ecuador, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Peru, and Colombia. In Colombia they are found between 9,500 and 13,000 feet above sea level, and their biodiversity is amazing.

It is estimated they are home to roughly:

Biodiversity in the paramos is similar to an island effect. Even though they may be relatively close to each other, their biodiversity is very different because the sea acts as a barrier. Over time, the populations become increasingly unique and differentiated from each other. In the case of the paramos, it is not the sea separating populations, but rather lowlands.

The conditions of the paramo favor endemism; a species is endemic if it is limited to a specific geographic area and is not found naturally in any other part of the world. According to the Humboldt Institute, of the 3,500 species of vascular plants (plants with stems and flowers) that live in the Andean paramos, 60% are endemic.

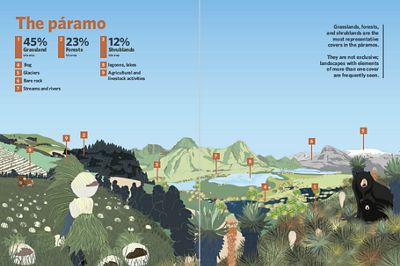

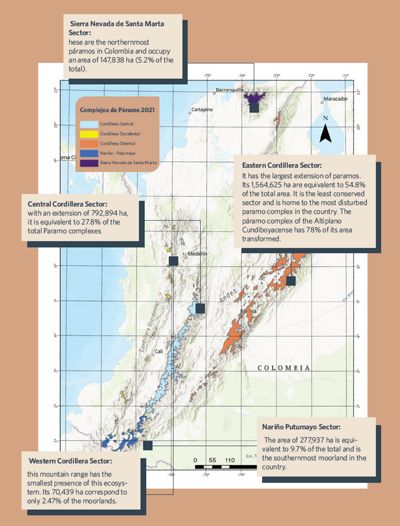

Colombia’s paramos, as defined by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development in 2021, cover 11,000 square miles.

Nearly half of the planet’s paramos are found here. Colombia’s paramos are located in five sectors, 17 districts, and 36 complexes. This area is equivalent to 2.5% of the country’s mainland, which makes Colombia by far the country with the largest expanse of paramos.

Human activity, especially agriculture and livestock farming, has had a significant impact on Colombia's paramos. The gradual replacement of natural covers with covers such as pasture or agricultural crops has long-term effects on the diversity and state of conservation of the paramo. With advances in agricultural technology, a number of crops have spread to increasingly higher altitudes.

Originally they were grown as rotation crops, which allowed the land to recover for years between harvests. With the advent of agrochemicals and improved crop varieties, the interval between harvests is much shorter and the land has less time to recover. Also, livestock farming has spread, gradually converting the paramo into pastureland.

Protecting the paramos and understanding their potential to help mitigate climate change, requires a deep understanding of the communities that depend on them. Over the years, there has been debate about the best way to manage the paramos to ensure the wellbeing of the ecosystem and its inhabitants.

Peace, quiet, and tranquility characterize the setting that has given hundreds of Colombians, such as Alicia Castellanos, a peasant farmer from the rural area of Manizales, well-being and quality of life. “It means everything to me,” she says. The paramos provide the people there with water and food; they make their living here through farming.

“It is important to remember that in Colombia the paramos are not uninhabited areas and that any conservation strategy must start from and be developed in partnership with the communities that inhabit them,” she says.

Watch the documentary in Spanish.

Local communities are essential to successfully restoring and conserving the paramos. For Camila Rodríguez, TNC Colombia’s Nature-based Solutions for Mitigation lead, the study not only sought to understand how these ecosystems can help us mitigate the climate crisis, but also how this information can be used to create innovative financial mechanisms to support paramo conservation and restoration, involving the people of these areas.

“In order to be successful, environmental projects must take into account the social realities of natural landscapes,” she says. Local communities, who are more familiar with these areas than almost anyone else, are key allies in protecting these ecosystems.

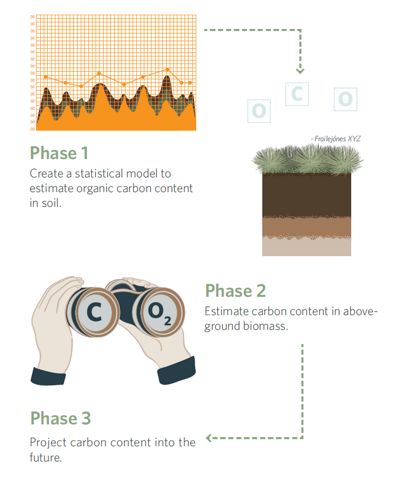

In 2021, TNC Colombia’s Nature-Based Solutions for Mitigation team set out to understand how much carbon páramos can store per hectare, how this carbon is released when land use is altered, and how quickly it could be captured if degraded areas are restored.

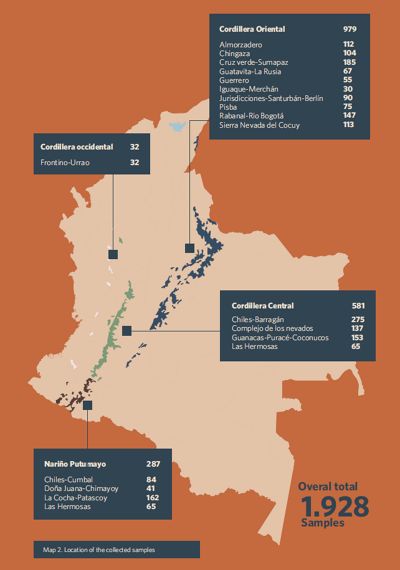

To obtain answers, the TNC mitigation team conducted several field trips and collected vegetation and soil samples at different points. They knew that carbon accumulation varies according to factors such as temperature, altitude, slope, exposure to wind and type of vegetation among other factors.

We collected data on every soil type we encountered to understand the carbon accumulation, gauge how much could potentially be captured by conservation and restoration in a given area, and estimate how much would be released if the soil were converted.

This graphic contains descriptions of three phases. Phase 1: Create a statistical modal to estimate organic carbon content in soil. Phase 2: Estimate carbon content in above-ground biomass. Phase 3: Project carbon content into the future.

Colombia’s paramos represent a variety of climatic, topographic, vegetation, and land use conditions. Because of this, data had to be collected and processed from many different locations throughout these paramos.

Taking the results from the previous research phase, the team of scientists used what’s called a Random Forest regression model to organize the carbon data and account for the other factors (slope, temperature, precipitation, topography, land cover).

Models like this use mathematical formulas to show the relationship between different variables and are frequently used to understand and describe natural phenomena. They are very useful for predicting values based on related variables, without the need to measure them directly.

This enables us to assign the number of tons of carbon per hectare (tC/ha) contained in the biomass for each cover, not only in the sampled sites but for every paramo in the country.

Thus, a map was created that shows the carbon content in the aerial biomass of the paramos for 2022. See Handbook page 58.

To predict how land use might change in the country’s paramos, it’s crucial to understand how different physical, social, economic, and political factors can influence these changes in terms of space, structure, and function.

Current regulations and the natural dynamics of Colombia make these effects worse. The loss of ecosystems and its impact on both nature and human communities is a major concern, highlighting the need to model these changes. Using maps of soil organic content and aboveground biomass from earlier phases, we predicted how carbon levels in the paramos might change in the future under different scenarios.

Trend software projected that from 2019 to 2050, 142,000 hectares of paramo could be turned into farmland. This change would directly increase carbon emissions, posing a significant challenge for managing heat.

For the TNC Colombia team, restoring degraded areas of the paramos can help capture large amounts of carbon:

Restoring 211,000 hectares would sequester 19 million tons of carbon in 28 years. Restoring 416,000 hectares would sequester 39 million tons of carbon in the same period of time. Restoring 15,000 hectares would increase groundwater availability by 2 percent. Reduce surface runoff by 1.5 percent, preventing erosion, flooding, drought, and other hazards.

Natural climate solutions (NCS) help lower greenhouse gas emissions and make us more resilient to climate change. They also offer extra benefits like protecting biodiversity and regulating the water cycle, which leads to better water availability and aquifer recharge. Because of these benefits, NCS have been studied in relation to protecting and restoring the paramos.

This project is part of a Global Network of Prototypes where The Nature Conservancy is leveraging its expertise to activate the potential of Natural Climate Solutions, testing and evaluating high-impact pathways that can be scaled and replicated around the world.

We hope this information can support the Colombian government in its upcoming process of updating its NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions).

Science shows that—combined with cutting fossil-fuel use and accelerating renewable energy—natural climate solutions can help us avoid the worst impacts of climate change.