The Sagebrush Sea Is Vanishing

Learn what The Nature Conservancy and stakeholders are doing to preserve one of the largest natural systems in North America.

What is the Sagebrush Sea?

Sometimes a landscape can trick you. What looks barren can teem with life. What feels endless can face limits. What seems plain can be magical. The Sagebrush Sea is not on any tourist must-see lists. You won’t find it decorating calendars or postcards. But this landscape has a vital job to do and an epic story to tell.

Sagebrush Sea By the Numbers

-

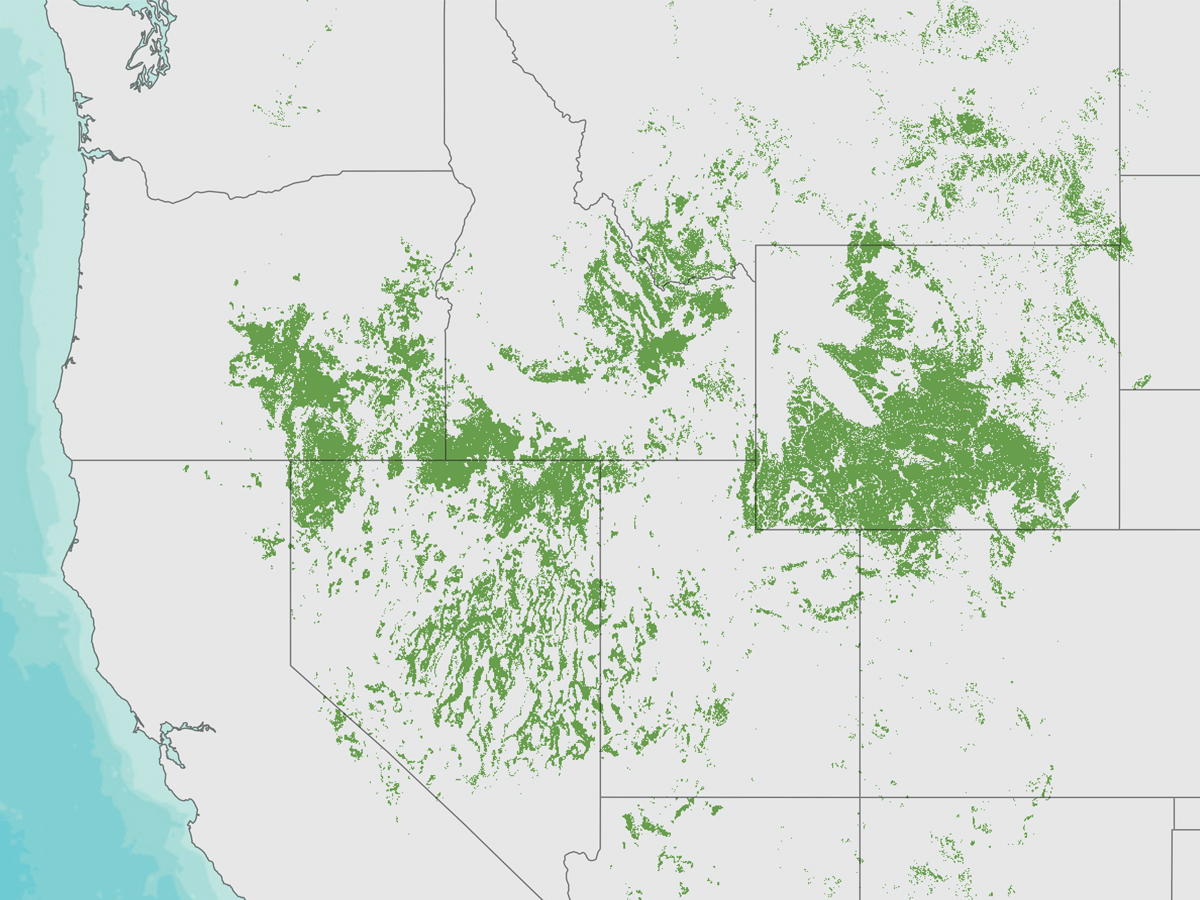

150

million acres, the size of the Sagebrush Sea across 13 western U.S. states.

-

350

Number of rare, threatened and endangered species that depend on this landscape.

-

14

million acres of intact sagebrush ecosystems lost since 1998.

-

6

TNC chapters working with partners to reverse declines in the sagebrush ecosystem.

Take Action

Donate today, and you can help us prevent this iconic landscape from disappearing and support the people, animals and local economies that depend on it.

Sagebrush once stretched across almost 500,000 square miles from the Dakotas to California. You know its features: Boundless skies. Big views. Blue-green sage and purple lupine stretched to the horizon. You also know its legacy. Think about the different cultures that have flourished here. And the cultures that have clashed. These rolling grasslands and plains have sustained tribes, tempted pioneers and birthed cowboys. They have witnessed terror, grit and hope.

Intertwined with the dense human saga, nature has its own narrative. The heart of the Sagebrush Sea is a complex vegetation network—a rich, diverse mix including sagebrush, bunchgrasses and wildflowers. Together these native plants sustain hundreds of animal species from burrowing owls and pygmy rabbits to mule deer, pronghorn and mountain lions. Many, like the iconic greater sage-grouse, can survive nowhere else.

Quote: Matt Cahill

We need scientific solutions and large-scale collaboration to reverse the trend in sagebrush. This is an all-hands-on-deck crisis.

Yet today, the Sagebrush Sea is a shadow of its former self. Every year we lose another one million acres to invasive species, catastrophic wildfire, development, improper grazing and climate change. Eight million people call this landscape home and depend on a healthy ecosystem to thrive. For these rural communities already under stress, a disappearing Sagebrush Sea drives ranchers out of business and leaves farmers without water for crops. The smoke from wildfires makes life in cities intolerable.

For our native wildlife, the loss of nesting grounds and migration corridors pushes them towards extinction.

For all of us, the fate of the Sagebrush Sea should matter. This is our chance to value our heritage and safeguard our future. It’s a chance to revive our core.

Improving Sagebrush Sea Habitat

TNC is working with partners and communities, improving sagebrush habitat in 11 states across the West. Seven chapters are engaged in the Sagebrush Sea Program—Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Montana, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming. Connecting partners, leveraging projects and sharing solutions across borders will accelerate the work.

Utah

TNC and The Bureau of Land Management used Landscape Conservation Forecasting ™, an ecological planning tool, to model cost-effective restoration on 900,000 acres including treating invasive plants and seeding perennial grasses, forbs and shrubs.

Idaho

Rinker Rock Creek Ranch is a living laboratory where TNC and partners are learning how to best manage rangeland for the benefit of people and nature, like showing how livestock grazing can be compatible with sage-grouse conservation.

Montana

TNC draws together partners to improve sagebrush habitat by removing encroaching trees, restoring wet meadows and removing fences. The partnership is a force for conservation, communication and collaboration in Montana’s High Divide Headwaters.

Nevada

TNC helps the largest gold mining company in the world mitigate its impacts using a planning tool called Landscape Conservation Forecasting™, designing thousands of acres of restoration to protect sagebrush habitat from wildfire. liz.munn@tnc.org

Oregon

TNC is scaling up seed restoration through the private sector by refining technologies that benefit native plants but are lighter, less expensive and more compatible with other tools than versions created before. jessie.griffen@tnc.org

Wyoming

TNC is experimenting with wildflowers to improve performance in restoration seedings, an essential step to restore plant communities. Learn more about how Wyoming is reclaiming the sage, or contact maggie.eshleman@tnc.org.

How are we protecting the Sagebrush Sea?

The Sagebrush Sea is disappearing at a devastating pace and scale. But we have a plan. Spanning six states, TNC’s Sagebrush Sea Program is an unprecedented effort to coordinate conservation work across this entire ecosystem. In seven states—Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming—there is a huge effort combining protection and policy work with ground-breaking restoration advances, public and industry partnerships and local community projects.

Our work to save the Sagebrush Sea spans three major fronts: restoration, management and protection.

Invasive Species and Sagebrush Restoration

Let’s face it: it’s not easy being a sagebrush seedling. Even in an average year, a young sagebrush plant faces the extremes of life in the American West: swings in temperature, high winds and dry conditions. Specially adapted to these elements, sagebrush sea plants are tough in many ways. But things are no longer average. Far from it.

“Restoration of the sagebrush steppe is a complex puzzle with many pieces. The unique partnership between TNC and the Agricultural Research Service is producing a new generation of science-based restoration technologies that will be put to a large enough scale necessary to affect positive change in the sagebrush sea.” Dr. Chad Boyd, Research Leader, USDA Agricultural Research Service.

Today native plant seedlings face a fight for survival from day one. One of the biggest threats is cheatgrass, a voracious invasive annual grass that has already infested 50 million acres of sagebrush steppe habitat and is spreading fast. And still other invasive annual grasses, like medusahead and ventenata, are even more tenacious. These invasives germinate earlier than native grasses, outcompeting natives for soil moisture and nutrients.

And they burn. With the first heat of summer, cheatgrass becomes a tinderbox that is easily ignited, devouring sagebrush in larger and more frequent wildfires. It’s a vicious cycle—and one that’s deadly for sagebrush and the wildlife it supports. Cheatgrass-fueled fires are also dangerous and stressful for communities who face a frightening “new normal” across the West.

Sagebrush champions face a major challenge: healing a landscape under constant attack. Once lost, the native plants that make up the sagebrush sea are difficult to restore in conditions that can be hostile to tiny seeds trying to take hold.

Partnering for Restoration

So how do we combat cheatgrass and give sagebrush and other native seedlings a fighting chance? We innovate, collaborate and think big. By working with USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) there is hope to pioneer ground-breaking restoration technologies designed to increase survival odds for seedlings. The team’s three key technologies include:

- Herbicide protection, which coats native seeds to protect them as a selective herbicide eliminates nearby cheatgrass and other invasives.

- Nutrient enhancement, which adds extra nutrients to sagebrush seeds to give them a boost to grow longer roots faster, and better withstand the increasing drought and competition.

- Germination delay, in which native seeds are coated with a film that delays how quickly they germinate. This practice allows scientists to ensure there are variable germination schedules for seeds, covering the bases so that at least some seeds survive the uncertain conditions of climate change.

For the last several years, TNC and ARS scientists have been testing and monitoring the use of seed technologies in Utah, Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada and Oregon. And the results are promising.

But it’s one thing to score restoration successes in small test plots. In the race to save the Sagebrush Sea, we know we need to go big. To develop scalable restoration products, there is a new ally: Germains® Seed Technology based in Gilroy, California. This commercial seed enhancement company offers us materials engineering expertise and industrial supply-chain processes. In short, they ramp-up our innovative seed-based restoration techniques to a whole new level.

TNC, ARS and Germains have agreed to create and test effective, scalable and commercially viable seed technologies specifically aimed at a large-scale seeding demonstration. We hope this is just the beginning of an effort that will put critical restoration tools in the right hands: public agencies. 70% of the Sagebrush Sea is found on public lands, so government agencies will play a key role in any successful bid at restoration.

“The idea here is that widespread use of these restoration technologies could help the Bureau of Land Management and other agencies reverse declines in sagebrush landscapes that have suffered a lot of impacts,” says Matt Cahill, Director of TNC’s Sagebrush Sea Program. "We expect the first results of our work with Germains to be ready in 2025.”

Greater Sage-Grouse: Two male sage-grouse face off against each other. © Ken Miracle

Long-billed Curlew: These coastal shorebirds summer in the sagebrush. © Kenton Rowe

Mule Deer: Three mule deer turn their heads to hear better. © Wolfe Repass/TNC Photo Contest 2019

Burrowing Owl: Long-legged birds that live in underground burrows. © ZhuoWen Chen

Pronghorn: A group of pronghorns stand together on alert. © Matthew Scott / TNC Photo Contest

Long-billed Curlew : Chicks use sagebrush as shelter from predators. © Kenton Rowe

Ferruginous Hawk: These hawks are the largest in North America. © Bebe Crouse / TNC

Pygmy Rabbit: Sagebrush is a huge portion of the pygmy rabbit diet. © Morgan Heim

Sage Thrasher: These birds mimic other birds that share its habitat. © Bill Schmoker

Tiger Beetle: Tiger beetles are known for their predatory speed. © Mike McDowell

Sagebrush Sea Management

Damage to the Sagebrush Sea is not new. From the early days of European settlement in the West, these lands faced uses and impacts that would ultimately alter them for generations. Historic overgrazing and the introduction of invasive species like cheatgrass, and later fragmentation by fencing, roads as well as residential and energy development, have all played a role in the loss of sagebrush and its critical understory of perennial bunchgrasses and wildflowers. Extreme drought and heat driven by climate change now exacerbate these problems.

“By focusing on the needs of the ecosystems and, in particular, the needs of important deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses, we believe there are ways to change public lands grazing permits that benefit livestock operators and the landscapes on which they work.” said Liz Munn, TNC's Resilient Public Land Strategy Director.

Today, the dynamic between people and the Sagebrush Sea remains complex. Large, working ranches and extensive livestock grazing allotments on public lands play a major role in the health of this ecosystem. The Bureau of Land Management alone is responsible for 78 million acres of sagebrush habitat. Grazing currently occurs on most of our public lands.

For ranch operators, the shrinking Sagebrush Sea impacts their daily lives. Invasive species put them at greater risk for wildfire and reduces healthy livestock forage. Yet ranchers face a serious challenge: how to adapt grazing practices to bolster an ailing landscape in a way that accounts for climate change and makes economic sense. And federal agencies, often with few resources and limited capacity, are trying to manage thousands of grazing leases, many of which are inflexible and not designed to cope with the scale of the crisis.

Collaborating with Landowners and Public Land Agencies

TNC owns or partners with ranches covering millions of acres across the West. Landowners and public land agencies are some of our best partners in the race to reverse the decline of sagebrush. Using working ranches as living laboratories across the West, the goal is to develop new models for well-managed grazing.

What is well managed grazing? We believe it’s a program built on these principles:

- Goals of resiliency—ensuring vegetation and wildlife thrive in the face of use and climate change

- Novel grazing approach—using innovative science to test new and progressive strategies

- Timely monitoring—ensuring that our practices are measurable and adaptive, so we can continually improve

- Feasible on public lands—working with agency partners to understand how to put these grazing approaches into public land grazing permits

- Economically-focused—making sure the ranchers’ bottom-line is a top priority so that economic incentive drives the adoption of these practices.

- Built on mutual trust—creating grazing programs collaboratively, with transparency, good communication and shared benefits

This approach is already underway with partners at the Winecup Gamble Ranch in the northeast corner of Nevada. Spanning 1 million acres, this privately owned ranch, with extensive sagebrush habitat and numerous public grazing allotments, is the perfect testing ground for well-managed grazing. The collaborative effort among NGOs, government partners and neighboring ranches - work to re-assess traditional ranch management and develop grazing practices that will reduce cheatgrass and promote the health of perennial bunchgrasses, as well as reduce the risk of dangerous fires. Every strategy the team develops must also meet the ranch’s economic needs and safeguard the well-being of the local community.

The work at the Winecup Gamble Ranch is exciting and new. It’s also just a first step. We envisions taking what we learn here—the core principles of a new grazing model—and adapting them to meet the specific needs of other large ranches with grazing permits throughout the Sagebrush Sea.

Sagebrush Sea Protection

Take a moment to imagine the American West as it would have looked 200 years ago. An uninterrupted sea of sagebrush would have covered 14 states and 3 Canadian provinces. The Native Americans and settlers would have witnessed many sights no longer possible today. One such spectacle? Huge flocks of an iconic, and now dwindling, species: the greater sage-grouse. At the time, there were as many as 16 million sage-grouse throughout the United States. Today, less than 200,000 remain.

Famous for their spring mating dance—a striking and noisy display of brilliant throat sacs, flashing feathers and impressive struts—the sage-grouse is a ground-dwelling bird wholly dependent on sagebrush for year-round food and shelter. And the sage-grouse is just one of hundreds of species who need sagebrush to survive.

There is no doubt that humans are changing the Earth—quickly. Experts warn that we have already drastically reduced the diversity of our planet’s plants and animals, and a million species are now at risk of extinction. The loss is not just about nature. We’re talking about the loss of jobs and revenue, food sources, healthy land, clean water and air—fundamental needs that matter to all of us. In North America, the continuing, rapid loss of the Sagebrush Sea is a tragedy unfolding right before our eyes.

Conservation Strategies and Easements

The greater sage-grouse puts a feathery face on the fate of the Sagebrush Sea—and it’s a species that is benefitting from a hallmark conservation strategy: land protection. Working with scientists and landowners throughout the West, we’re identifying the highest priority and most vulnerable habitats and migration corridors for species like the sage-grouse—and then we’re joining forces to safeguard them, acre by acre.

How are we doing this? By using conservation easements, which are one of the most powerful, effective tools available for the permanent protection of private lands in the United States. An easement is a voluntary agreement by a landowner that prevents development and protects natural values of the land.

For example, TNC worked with the Tanner, Christiansen and Pugsley families to secure easements on properties encompassing nearly 10,000 acres in northwest Utah. Funded in part by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the transactions protect some of the state’s best remaining sage-grouse habitat on private land.

Quote: Jay Tanner

We believe what's good for the bird is good for the herd.

Jay Tanner, whose family owns several of the properties now under easement, is a long-time rancher who understands the warning signs of the grouses’ decline. “A sagebrush landscape may not look like much to the average person, but its good health holds the key to a strong environment and our local agriculture-based economy,” says Tanner. “We believe what’s good for the bird is good for the herd.”

This idea, that livestock operators and wildlife can live in harmony with good stewardship practices, rings true throughout the West. In Montana, using funds from the Sage-Grouse Initiative, TNC collaborated with two ranches in the High Divide to provide socio-economic and ecological benefits on over 45,000 acres of sagebrush grasslands. And in other communities throughout the Sagebrush Sea, there is ongoing work with public and private partners to provide resources to help landowners improve their management practices and restore degraded habitat.

Sometimes, development impacts to wildlife habitat can’t be avoided, so it's important we work with partners to develop programs to help offset—or mitigate—the impacts by protecting or restoring land in different locations or offering financial compensation for the new disturbance that can be used on restoration, protection or land acquisition elsewhere. For example, TNC helped design Oregon’s sage-grouse mitigation program to steer energy development away from sensitive breeding areas.

In the American West, consensus on land, water and wildlife issues is rare. The sheer number of stakeholders, with diverse motivations and complex connections to the land, makes for a melting pot of opinions and agendas. Yet, the plight of the Sagebrush Sea and its importance to rural communities and to wildlife like the greater sage-grouse is a proving a powerful catalyst for unity. Using TNC’s deep, West-wide relationships, and 70-year track record of land protection, we are scoring big, on-the-ground wins for people and nature.

Sagebrush Scientists

TNC scientists work diligently to restore, manage and protect the Sagebrush Sea. Meet the experts who are devoting their careers to this iconic and expansive landscape.

Sagebrush Sea Director

Matt Cahill

Matt leads The Nature Conservancy’s Sagebrush Sea Program, a collection of six states working together to improve conservation outcomes in sagebrush ecosystems. Together these states—Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah and Wyoming—are focused on innovative solutions that can improve restoration success and reverse the trend of degradation and wildfire in rangelands across the American West. Matt began with The Nature Conservancy in 2015, first as an ecologist implementing restoration in Oregon’s sagebrush steppe, then as a collaboration specialist bringing partners together to find solutions to rangeland management issues. Matt lives in Bend, Oregon.

Areas of expertise: sagebrush ecology, program management, Bureau of Land Management, partnerships and collaborations

Sagebrush Conservation Team

- Sean Claffey, Southwest Montana Sagebrush Conservation Coordinator

- Maggie Eshleman, Wyoming Restoration Scientist

- Jessie Griffen, Restoration Project manager

- Liz Munn, Resilient Public Lands Strategy Director

- Corinna Riginos, PhD, Wyoming Science Director

For all media inquries, please contact Tracey Stone at tstone@tnc.org.