The Sagebrush Sea Is Vanishing

Learn what The Nature Conservancy is doing to preserve one of the largest natural systems in North America.

What is the Sagebrush Sea and Why Does it Matter?

Sometimes a landscape can trick you. What looks barren can teem with life. What feels endless can face real limits. What seems plain can be magical. The Sagebrush Sea is a vast and essential part of the American West, playing a vital role in the region’s ecology, economy and cultural identity.

Sagebrush Sea By the Numbers

-

150

million acres, the size of the Sagebrush Sea across 13 western U.S. states.

-

350

Number of rare, threatened and endangered species that depend on this landscape.

-

14

million acres of intact sagebrush ecosystems lost since 1998.

-

7

TNC chapters working with partners to reverse declines in the sagebrush ecosystem.

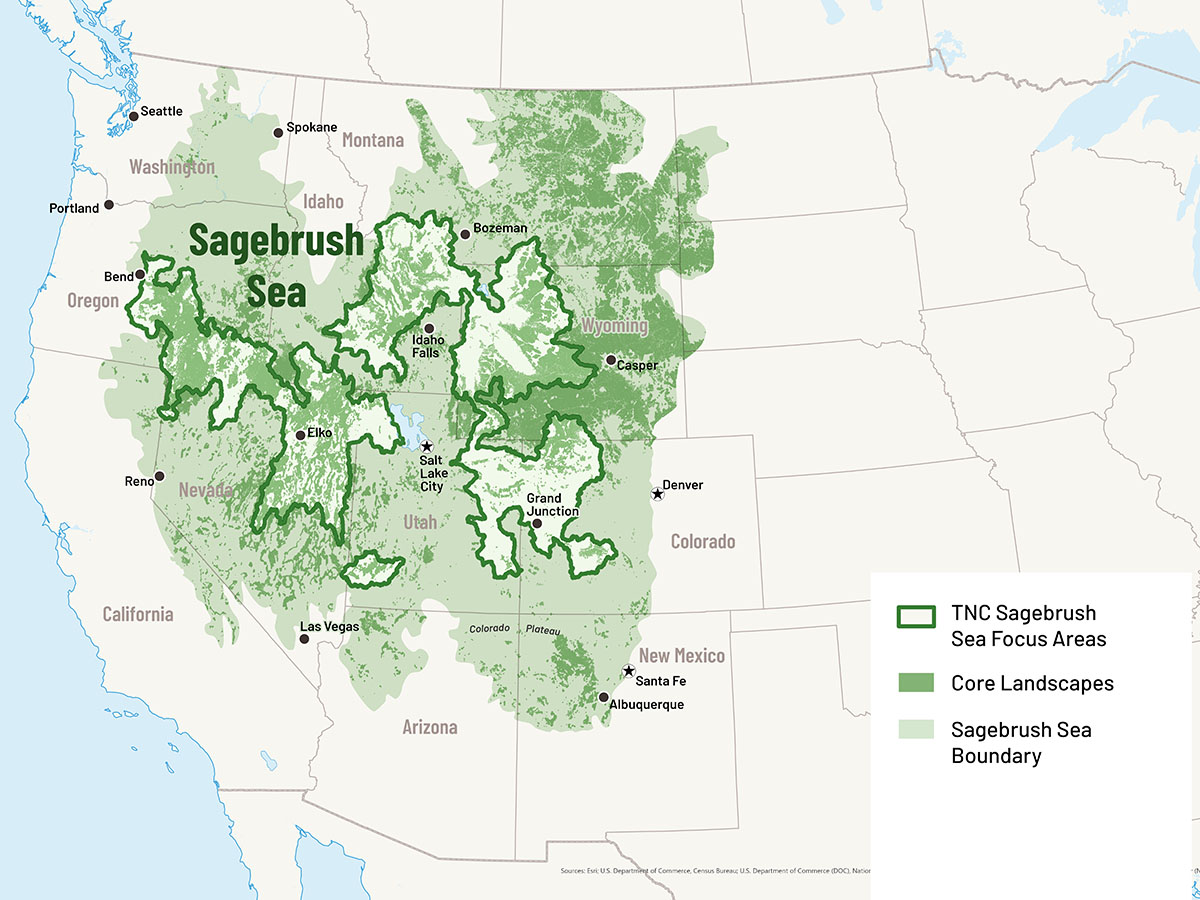

The Sagebrush Sea is disappearing at a devastating pace and scale—but we have a plan. Spanning Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming, The Nature Conservancy’s Sagebrush Sea Program is an unprecedented effort to coordinate conservation across this vast and threatened landscape.

Once stretching nearly 500,000 square miles from the Dakotas to California, the Sagebrush Sea offered boundless skies, blue-green sage, and sweeping plains dotted with lupine and bunchgrass. These lands have sustained Indigenous Peoples for millennia, tempted pioneers and birthed cowboys. It’s a landscape marked by both hope and hardship, resilience and conflict.

Quote: Matt Cahill

We need scientific solutions and large-scale collaboration to reverse the trend in sagebrush. This is an all-hands-on-deck crisis.

Stay up-to-date with conservation near you!

Sign up to receive monthly conservation updates and learn how you can get involved.

Nature, too, tells a powerful story here. The Sagebrush Sea hosts a complex web of native plants—sagebrush, bunchgrasses, wildflowers—that support more than 350 species of conservation concern. From pygmy rabbits and burrowing owls to mule deer and pronghorn, wildlife depends on this ecosystem. Some, like the greater sage-grouse, live nowhere else.

But this iconic landscape is vanishing. Each year, one million more acres are lost to invasive species, catastrophic wildfire, climate change, development and improper grazing. Eight million people call this region home—many in rural communities already under strain. As the Sagebrush Sea shrinks, ranchers go out of business, farmers lose water and wildfire smoke chokes cities hundreds of miles away.

This is a moment to act. Conserving the Sagebrush Sea means protecting a legacy—and a future. It’s a chance to revive our ecological core, support working lands and sustain the wild character of the West.

Improving Sagebrush Sea Habitat

TNC is working with partners and communities, improving sagebrush habitat in 11 states across the West. Seven chapters are engaged in the Sagebrush Sea Program—Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Montana, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming. Connecting partners, leveraging projects and sharing solutions across borders will accelerate the work.

Utah

TNC and The Bureau of Land Management used Landscape Conservation Forecasting ™, an ecological planning tool, to model cost-effective restoration on 900,000 acres including treating invasive plants and seeding perennial grasses, forbs and shrubs.

Idaho

Rinker Rock Creek Ranch is a living laboratory where TNC and partners are learning how to best manage rangeland for the benefit of people and nature, like showing how livestock grazing can be compatible with sage-grouse conservation.

Montana

TNC draws together partners to improve sagebrush habitat by removing encroaching trees, restoring wet meadows and removing fences. The partnership is a force for conservation, communication and collaboration in Montana’s High Divide Headwaters.

Nevada

TNC helps the largest gold mining company in the world mitigate its impacts using a planning tool called Landscape Conservation Forecasting™, designing thousands of acres of restoration to protect sagebrush habitat from wildfire.

Oregon

TNC is working in partnership with the Oregon Desert Land Trust at Trout Creek Ranch to demonstrate emerging conservation techniques for stream and spring restoration and sustainable grazing to safeguard the sagebrush and rangeland landscapes we all depend on.

Wyoming

TNC is experimenting with wildflowers to improve performance in restoration seedings, an essential step to restore plant communities. Learn more about how Wyoming is reclaiming the sage.

Colorado

In the Yampa and White River basins, TNC and the Bureau of Land Management are using low-tech, process-based restoration like beaver dam analogs to slow water, restore rivers, and revitalize sagebrush habitat that supports wildlife, communities and working lands.

The Four Pillars of TNC’s Sagebrush Sea Program

Our conservation work is built around Upland Restoration, Riparian Restoration, Grazing Management and Large Landscape Protection.

Upland Restoration

Uplands in the Sagebrush Sea are naturally harsh—hot, dry, windy and unpredictable. Native plants evolved to survive here, but invasive annual grasses like cheatgrass are reshaping these systems in destructive ways. These fast-growing invaders outcompete native species, dry out early and fuel larger, hotter wildfires—creating a cycle that clears the way for even more invasives.

Breaking this weeds-and-wildfire cycle is one of the West’s most urgent conservation challenges. Restoring healthy uplands is difficult but essential—for wildlife, for climate resilience and for the safety of people and communities.

Across the range, TNC and our partners are advancing many upland projects, using science-based planning, targeted treatments and long-term monitoring. One example comes from Nevada, where a decade-long collaboration is showing what is possible at scale.

For 10 years, Liz Munn, TNC in Nevada’s Resilient Public Lands Strategy director, has helped lead an ambitious partnership with Nevada Gold Mines to restore sagebrush uplands damaged by wildfire and invasive grasses. In one area severely degraded after a 2007 fire, coordinated planning and sustained investment have brought the landscape back to life. Today, sagebrush and native grasses are returning, and the land once again supports wildlife and grazing cattle.

One striking sign of success: biologists counted 45 male sage-grouse on leks this spring—the highest number since the project began—at a site once on the brink of collapse. High-resolution remote sensing and ecological modeling helped guide treatments to the places where they mattered most.

“To walk out in the field this spring and see it come back to life—it was very gratifying,” Munn said.

This project offers something rare and powerful: evidence that large-scale upland restoration in the Sagebrush Sea can work. And it represents just one strategy within a broader, landscape-wide effort. From intensive restoration in Nevada to early-detection weed management in Wyoming and post-fire rehabilitation in Oregon, the seven-state Sagebrush Sea Program is applying science, partnerships and shared learning to replicate success across the entire range.

Riparian Restoration

Riparian areas—the ribbons of green shaped by streams, springs and wetlands—cover only a fraction of the Sagebrush Sea, yet support about 80% of its wildlife. Elk and deer raise young here, sage-grouse and other birds nest and feed, and amphibians like the northern leopard frog depend on these damp habitats. For people, healthy riparian zones recharge groundwater, buffer against drought and wildfire, and sustain farmers, ranchers and their herds.

Across the West, streams that once nourished the land now dry out faster and stay dry longer, threatening livelihoods and wildlife as hotter, drier conditions take hold. Restoring these waterways is among the region’s greatest conservation opportunities.

The Nature Conservancy is advancing restoration through low-tech, process-based restoration (LTPBR). Using simple materials—posts, rocks, willows and sagebrush—crews mimic the work of beavers to slow and spread water, reconnect floodplains and rebuild wetlands in arid landscapes. What makes this approach unique is its simplicity, accessibility and proven cost-effectiveness across large scales: modest interventions can yield profound results.

In Colorado’s Yampa and White River basins, Joe Leonhard and his team have used these techniques to transform parched channels into wet meadows, creating habitat for wildlife while improving forage and water security for ranchers.

The benefits ripple outward. Local crews—often young people from nearby communities—gain conservation skills and career pathways. Landowners and tribal partners see their land and herds thrive. Across the region, each restored stream adds resilience to entire watersheds, from salmon country in the Pacific Northwest to the sandstone canyons of southern Utah.

“It’s easy to overlook the smallest streams,” Leonhard notes. “Yet by restoring them across the West, we are building resilience and transforming landscapes.”

Riparian restoration in the Sagebrush Sea shows that even in an era of drought and rising temperatures, rivers can be renewed—and with them, the wildlife and communities that depend on them.

Grazing Management

Damage to the Sagebrush Sea is not new. From the early days of European settlement in the West, these lands faced uses and impacts that would ultimately alter them for generations. Historic overgrazing and the introduction of invasive species like cheatgrass, and later fragmentation by fencing, roads as well as residential and energy development, have all played a role in the loss of sagebrush and its critical understory of perennial bunchgrasses and wildflowers. Extreme drought and heat driven by climate change now exacerbate these problems.

By focusing on the needs of the ecosystems and, in particular, the needs of important deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses, we believe there are ways to change public lands grazing permits that benefit livestock operators and the landscapes on which they work.

Today, the dynamic between people and the Sagebrush Sea remains complex. Large, working ranches and extensive livestock grazing allotments on public lands play a major role in the health of this ecosystem. The Bureau of Land Management alone is responsible for 78 million acres of sagebrush habitat. Grazing currently occurs on most of our public lands.

For ranch operators, the shrinking Sagebrush Sea impacts their daily lives. Invasive species puts them at greater risk for wildfire and reduces healthy livestock forage. Yet ranchers face a serious challenge: how to adapt grazing practices to bolster an ailing landscape in a way that accounts for climate change and makes economic sense. And federal agencies, often with few resources and limited capacity, are trying to manage thousands of grazing leases, many of which are inflexible and not designed to cope with the scale of the crisis.

TNC owns or partners with ranches covering millions of acres across the West. Landowners and public land agencies are some of our best partners in the race to reverse the decline of sagebrush. Using working ranches as living laboratories, the goal is to develop new models for well-managed grazing.

Among the tools being tested is virtual fencing, an emerging technology that allows land managers to control where livestock graze. This approach can improve rangeland health by reducing pressure on sensitive areas, increasing flexibility for ranchers, and cutting down on the environmental footprint of fencing infrastructure.

Large Landscape Protection

The greater sage-grouse puts a feathery face on the fate of the Sagebrush Sea—and it’s a species that is benefiting from a hallmark conservation strategy: land protection. Working with scientists and landowners throughout the West, we’re identifying the highest priority and most vulnerable habitats and migration corridors for species like the sage-grouse—and then we’re joining forces to safeguard them, acre by acre.

How are we doing this? By using conservation easements, which are one of the most powerful, effective tools available for the permanent protection of private lands in the United States. An easement is a voluntary agreement by a landowner that prevents development and protects natural values of the land.

For example, TNC worked with the Tanner, Christiansen and Pugsley families to secure easements on properties encompassing nearly 10,000 acres in northwest Utah. Funded in part by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the transactions protect some of the state’s best remaining sage-grouse habitat on private land.

Jay Tanner, whose family owns several of the properties now under easement, is a long-time rancher who understands the warning signs of the grouses’ decline. “A sagebrush landscape may not look like much to the average person, but its good health holds the key to a strong environment and our local agriculture-based economy,” says Tanner. “We believe what’s good for the bird is good for the herd.”

This idea, that livestock operators and wildlife can live in harmony with good stewardship practices, rings true throughout the West. In Montana, using funds from the Sage-Grouse Initiative, TNC collaborated with two ranches in the High Divide to provide socio-economic and ecological benefits on over 45,000 acres of sagebrush grasslands. And in other communities throughout the Sagebrush Sea, there is ongoing work with public and private partners to provide resources to help landowners improve their management practices and restore degraded habitat.

Sometimes, development impacts to wildlife habitat can’t be avoided, so it's important we work with partners to develop programs to help offset—or mitigate—the impacts by protecting or restoring land in different locations or offering financial compensation for the new disturbance that can be used on restoration, protection or land acquisition elsewhere. For example, TNC helped design Oregon’s sage-grouse mitigation program to steer energy development away from sensitive breeding areas.

In the American West, consensus on land, water and wildlife issues is rare. The sheer number of stakeholders, with diverse motivations and complex connections to the land, makes for a melting pot of opinions and agendas. Yet, the plight of the Sagebrush Sea and its importance to rural communities and to wildlife like the greater sage-grouse is a proving a powerful catalyst for unity. Using TNC’s deep, West-wide relationships, and 70-year track record of land protection, we are scoring big, on-the-ground wins for people and nature.

Greater Sage-Grouse: Two male sage-grouse face off against each other. © Ken Miracle

Long-billed Curlew: These coastal shorebirds summer in the sagebrush. © Kenton Rowe

Mule Deer: Three mule deer turn their heads to hear better. © Wolfe Repass/TNC Photo Contest 2019

Burrowing Owl: Long-legged birds that live in underground burrows. © ZhuoWen Chen

Pronghorn: A group of pronghorns stand together on alert. © Matthew Scott / TNC Photo Contest

Long-billed Curlew : Chicks use sagebrush as shelter from predators. © Kenton Rowe

Ferruginous Hawk: These hawks are the largest in North America. © Bebe Crouse / TNC

Pygmy Rabbit: Sagebrush is a huge portion of the pygmy rabbit diet. © Morgan Heim

Sage Thrasher: These birds mimic other birds that share its habitat. © Bill Schmoker

Tiger Beetle: Tiger beetles are known for their predatory speed. © Mike McDowell

Sagebrush Sea Director

Matt Cahill

Matt leads The Nature Conservancy’s Sagebrush Sea Program, a collection of seven states working together to improve conservation outcomes in sagebrush ecosystems. Together these states—Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Colorado, Utah and Wyoming—are focused on innovative solutions that can improve restoration success and reverse the trend of degradation and wildfire in rangelands across the American West. Matt began with The Nature Conservancy in 2015, first as an ecologist implementing restoration in Oregon’s sagebrush steppe, then as a collaboration specialist bringing partners together to find solutions to rangeland management issues. Matt lives in Bend, Oregon.

Areas of expertise: sagebrush ecology, program management, Bureau of Land Management, partnerships and collaborations

Our Team

The Sagebrush Sea Program, led by Matt Cahill, brings together scientists, practitioners and strategists working across seven Western states to conserve and restore this vast ecosystem.

Sagebrush Sea Program Leadership Team

- Lee Davis, Western Rangelands Public Lands Policy Specialist

- Austin Rempel, Riparian Restoration Program Manager

- Megan Creutzburg, Upland Restoration Program Manager

- Adrienne Hoskins, Grazing Management Program Manager

- Jim Breitinger, Sagebrush Sea Marketing and Communications Director

Sagebrush Sea Program State Leads

- Colorado: Nancy Fishbein, Colorado Director of Resilient Lands

- Idaho: Kerey Barnowe-Meyer, Idaho Director of Conservation

- Montana: Jim Berkey, High Divide Headwaters Director

- Nevada: Liz Munn, Resilient Public Lands Strategy Director

- Oregon: Anya Tyson, Oregon Sagebrush Sea Program Director

- Utah: Danna Baxley, Utah Water and Agriculture Strategy Director

- Wyoming: Anika Mahoney, Wyoming Sagebrush Program Director

Program Support

In addition to the leadership team and state leads, the Sagebrush Sea Program is supported by key staff advancing restoration, science and collaboration across the seven states.

For all media inquries, please contact Claire Cornell at claire.cornell@tnc.org.