From Jaguars to Waterfalls: One Warbler’s Northbound Odyssey

Learn about the incredible 4000 mile journey blackburnian warblers embark on each spring using The Nature Conservancy's network of preserves for resting and refueling.

Explore some of the bird species that bring Appalachian skies to life each autumn and spring.

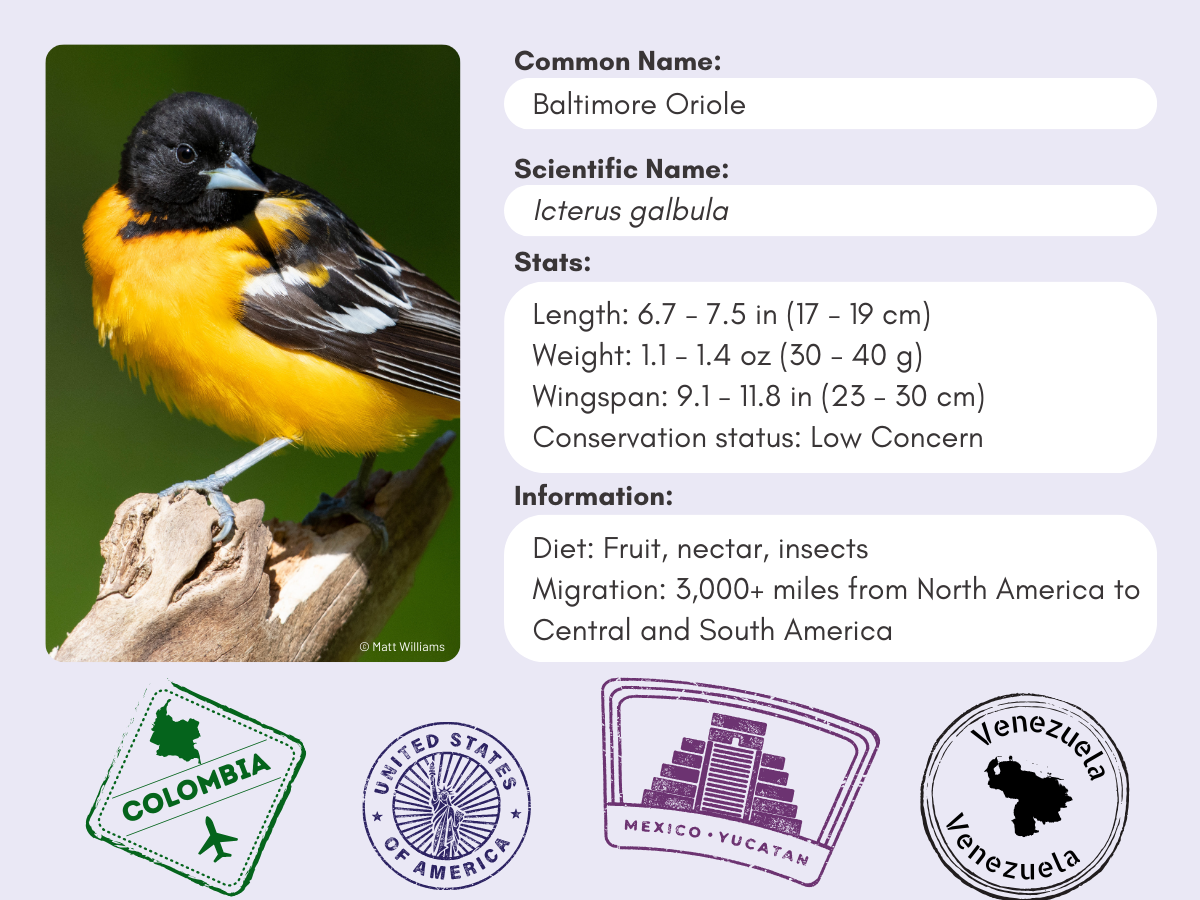

It’s early spring on the Yucatan Peninsula, and the days are starting to get longer as the northern hemisphere begins to warm. For the millions of Baltimore orioles that have spent the winter in the Maya Forest—the largest remaining tropical rainforest in the Americas—the longer days are triggering physiological and hormonal changes, signaling that it’s almost time to migrate north to the bountiful Appalachian Forest, which stretches almost 2,000 miles from Alabama to the Canadian Maritimes and serves as breeding grounds for nearly 100 migratory bird species.

For many orioles headed to Appalachia, the journey begins with a nonstop 600‑mile, 12‑hour flight across the Gulf. To prepare for the journey, they gorge on insects, fruits and nectar to build the fat reserves needed for the trip, then wait for favorable winds and a warm front to launch northward.

After crossing the Gulf, orioles bound for Appalachia follow forest corridors and river systems, feeding on hatching insects and spring blooms. Upon arrival, females construct their signature basket-like hanging nests—intricately woven from materials such as milkweed fibers, cottonwood fluff and long grasses. Sturdy and expertly crafted, these nests are sometimes reused for multiple years.

Baltimore orioles—along with hundreds of other species of migratory birds—perform marvelous and incredible feats on their long journeys. Migratory birds have entertained and fascinated humans for millennia, and conservationists have studied bird populations as important indicators of ecosystem health across large geographies.

Like a firecracker in the sky, the Baltimore oriole dazzles with its orange, black and white plumage. These treetop dwellers begin their southbound migration as early as July, using the Appalachian Mountains as a natural highway for north-south navigation, stopovers and energy-saving updrafts. Along the way, they refuel on insects, fruit and water in lush valleys. Their journey spans more than 3,000 miles to Central and South America, reaching as far south as Central Colombia and Venezuela. This journey includes a nonstop 600-mile flight across the Gulf that normally lasts 11–12 hours. When they finally reach tropical forests, they’re exhausted and in urgent need of food and shelter, making the protection of these tropical habitats just as critical as conserving their Appalachian home.

Matthew D. Medler; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

The Baltimore oriole’s song is a short, rich, flutelike series of whistled notes, most often sung by males to establish and defend territory. Both sexes also use sharp calls—a staccato chatter during aggressive encounters and a repetitive “chuck” as an alarm that nearby orioles readily respond to. During breeding season, males may add a distinctive flutter-drum created by beating their wings loudly in flight.

Subscribe for the latest conservation news, updates, and ways to get involved.

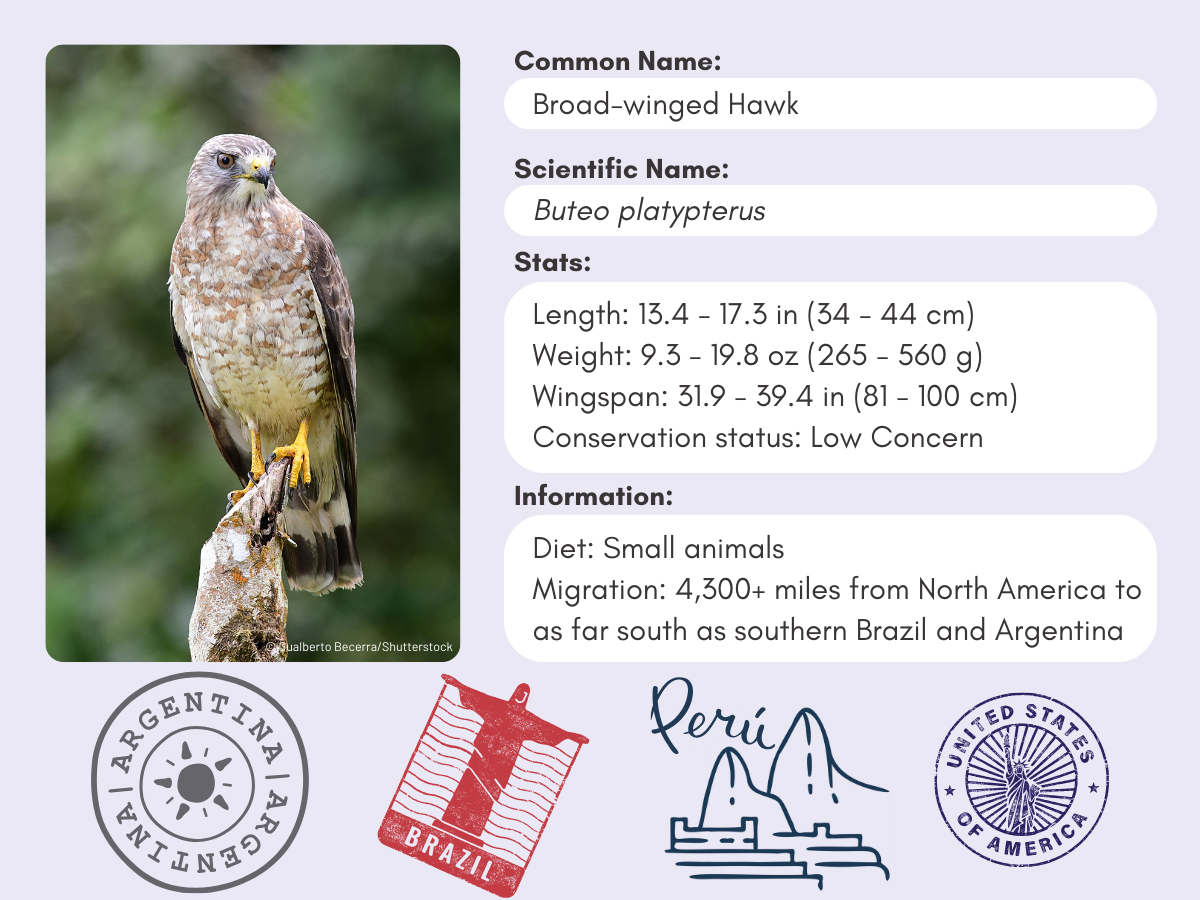

This small bird of prey can be tricky to spot in the spring and summer months, but keep your eyes open in the fall as huge, swirling flocks of broad-winged hawks make their annual migration from eastern North America to South America. These flocks are also known as “kettles,” referring to the illusion of someone using a spoon to stir a large pot of hawks in the sky. The broad-winged hawk uses the Appalachians as a crucial migratory corridor, taking advantage of mountain updrafts and rising hot air along ridge lines to conserve energy as they make their more than 4,300-mile journey as far south as central and southern Brazil and northern Argentina. Your best chance of catching a glimpse of broad-winged hawks is during the fall migration at places like Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania.

Robert C. Stein; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Broad-winged hawks have a high-pitched whistle that can last anywhere from 2-4 seconds. The first note is normally shorter than the second note. The male's call is an octave higher than the female's, and they give this call on the nest and in flight.

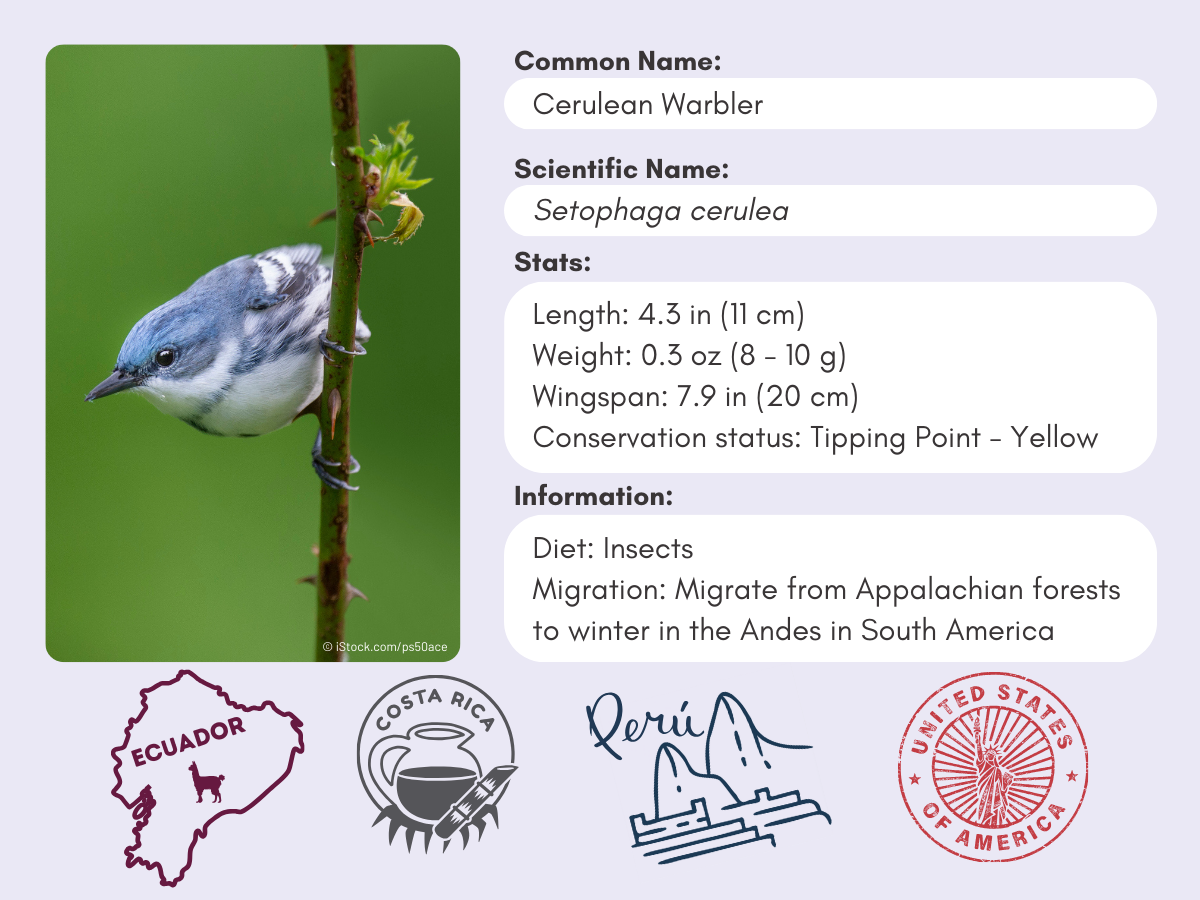

The small but beautifully colored cerulean warbler has been a catalyst for conservation action both in the Appalachians and South America. It’s estimated that the warbler’s population has decreased as much as 70% since the 1960s, mostly due to habitat loss and degradation, highlighting the need for healthy forests and habitat conservation to safeguard biodiversity. Cerulean warblers hunt for insects and breed in tall forests in the U.S. before flying south to winter on the slopes of the Andes.

Garrett MacDonald; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

The cerulean warbler’s song is a fast, buzzy, rising series of notes that often ends with an emphatic trill, delivered from high in the forest canopy. Males sing persistently during the breeding season to claim territory and attract a mate, while both sexes use sharp chip calls to stay in contact or signal alarm. Their bright, wiry song can be surprisingly powerful for such a small bird, helping it carry through dense treetops.

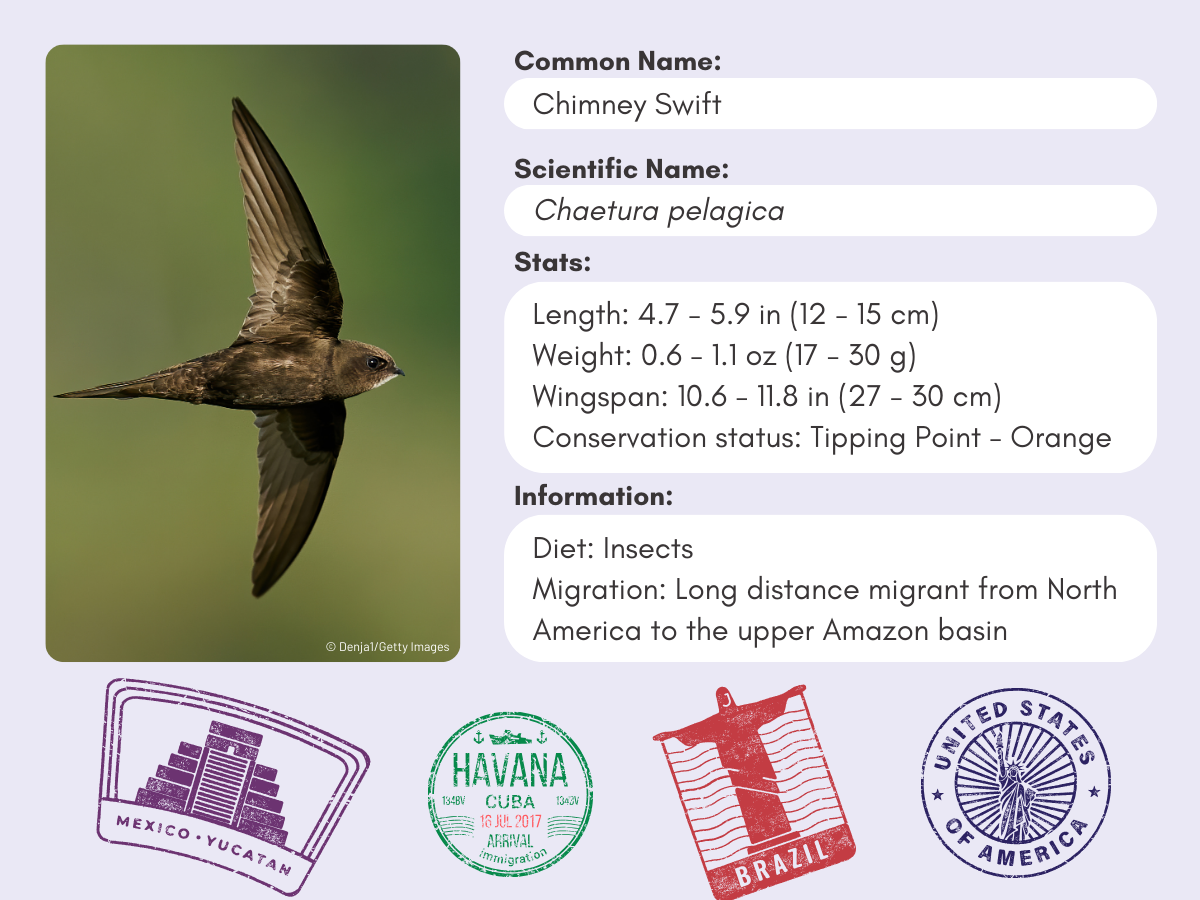

The chimney swift was more common in old-growth Appalachian forests prior to extensive human development and would nest in dead tree cavities, hollows or caves. Nowadays, these aerial acrobats are more easily spotted coming in and out of chimneys, bridges or old buildings. There, they spend their evenings in small nests attached to hard surfaces by their sticky saliva. Once fall comes, however, the chimney swift embarks on a long-distance migration to find similar accommodations in the upper Amazon basin of South America.

Wil Hershberger; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Chimney swifts give rapid, high‑pitched chattering calls—sharp, dry chips and twitters—that they exchange almost constantly in flight. Their calls help maintain contact among flock members as they forage overhead or swirl into chimneys to roost. The nonstop, buzzy chatter is a defining sound of summer skies wherever these aerial insect hunters gather.

While golden eagles are an iconic sight in the West, there are a few hundred pairs estimated in the East. Eastern golden eagles are rare and highly localized, breeding mainly in northern Quebec and Labrador in the spring. The population is small, migratory and conservation-sensitive, relying heavily on Appalachian ridges for migration and winter habitat. Appalachian ridges act like a thermal highway, giving the eagles the updrafts they need for energy-efficient travel. One of the best places to witness this migration is the Allegheny Front, a critical ecosystem that serves as a key stopover and observation point for these raptors. By November, many eagles settle in the central and southern Appalachians, including West Virginia and Virginia, to spend the winter months.

Gerrit Vyn; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Golden eagles are generally quiet birds, but they give high, thin whistles—often described as weak, piping calls—especially during territorial displays or interactions between mates. Nestlings and juveniles are more vocal, producing repeated, high‑pitched begging calls that carry across long distances. Adults sometimes utter short barks or chirps near the nest or when threatened, but most of their communication is subtle and infrequent.

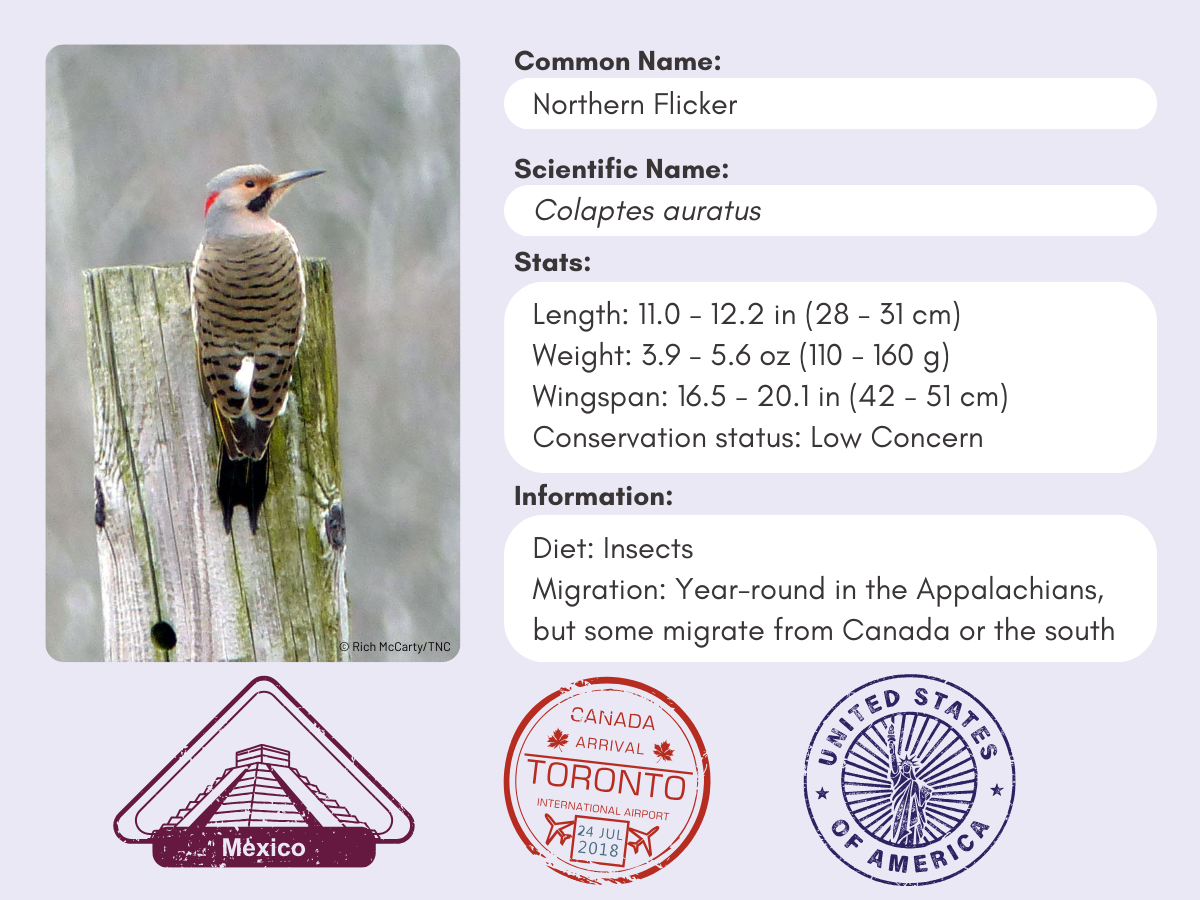

Despite being a member of the woodpecker family, the northern flicker actually prefers to find food on the ground, where they use their long-barbed tongue to lick up ants and other insects. Many of these birds are year-round residents in the Appalachians, but some may only visit us in the winter or summer after migrating from Canada or the Southern U.S., depending on whether they’re trying to beat the heat or escape the cold.

Ian Davies; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

The northern flicker’s primary song is a loud, rolling rattle with a piercing tone that rises and falls over several seconds, most often heard in spring and early summer. It also gives a sharp single‑note kyeer call and a softer, rhythmic wick‑a, wick‑a during close interactions. Like other woodpeckers, it produces rapid, evenly spaced drumming on wood or metal surfaces, which functions much like a song in territorial communication.

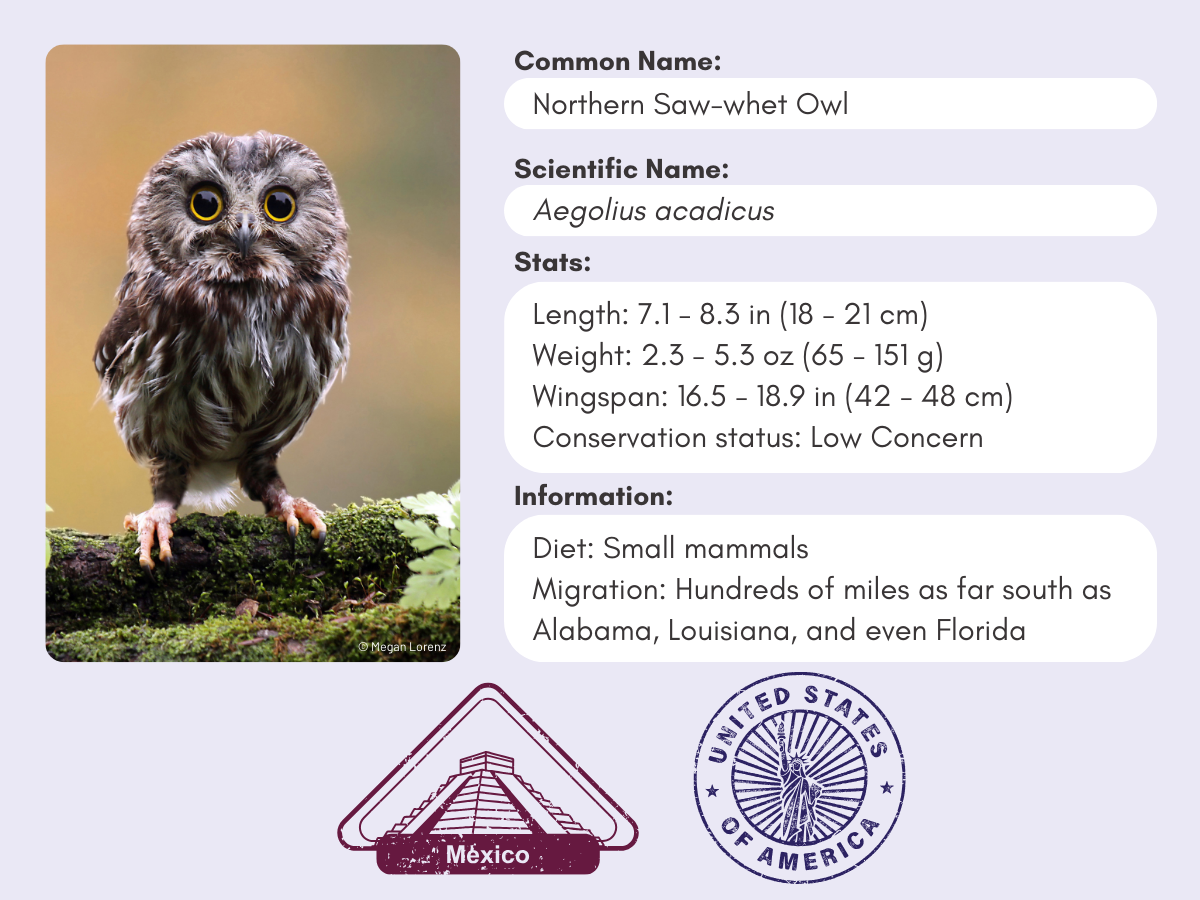

Have you ever seen an owl that looks stunningly similar to your cat? Well, it might not knock over your unattended glass of water, but the northern saw-whet owl certainly has the same devious look on its face. Though these owls tend to stay in their home range, each fall, many slip south under the cover of darkness, following forested corridors like the Appalachian Mountains. Some travel hundreds of miles, reaching as far south as Alabama, Louisiana and even Florida for the winter. Their migration is unpredictable, and big “irruption” years send waves of owls farther than usual. Irruption means an irregular, large-scale movement outside their normal range, often triggered by food shortages. The Appalachians remain a vital pathway, offering shelter and stopover sites for these travelers.

Thomas G. Sander; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

The northern saw-whet owl’s signature sound is a high, rhythmic too‑too‑too call, repeated at roughly two notes per second and commonly heard at night during the breeding season. It also gives a variety of other vocalizations—including loud squeaks, barks and whines—used in alarm or close‑range communication. Despite its small size, its territorial call can carry surprisingly far, sometimes up to half a mile.

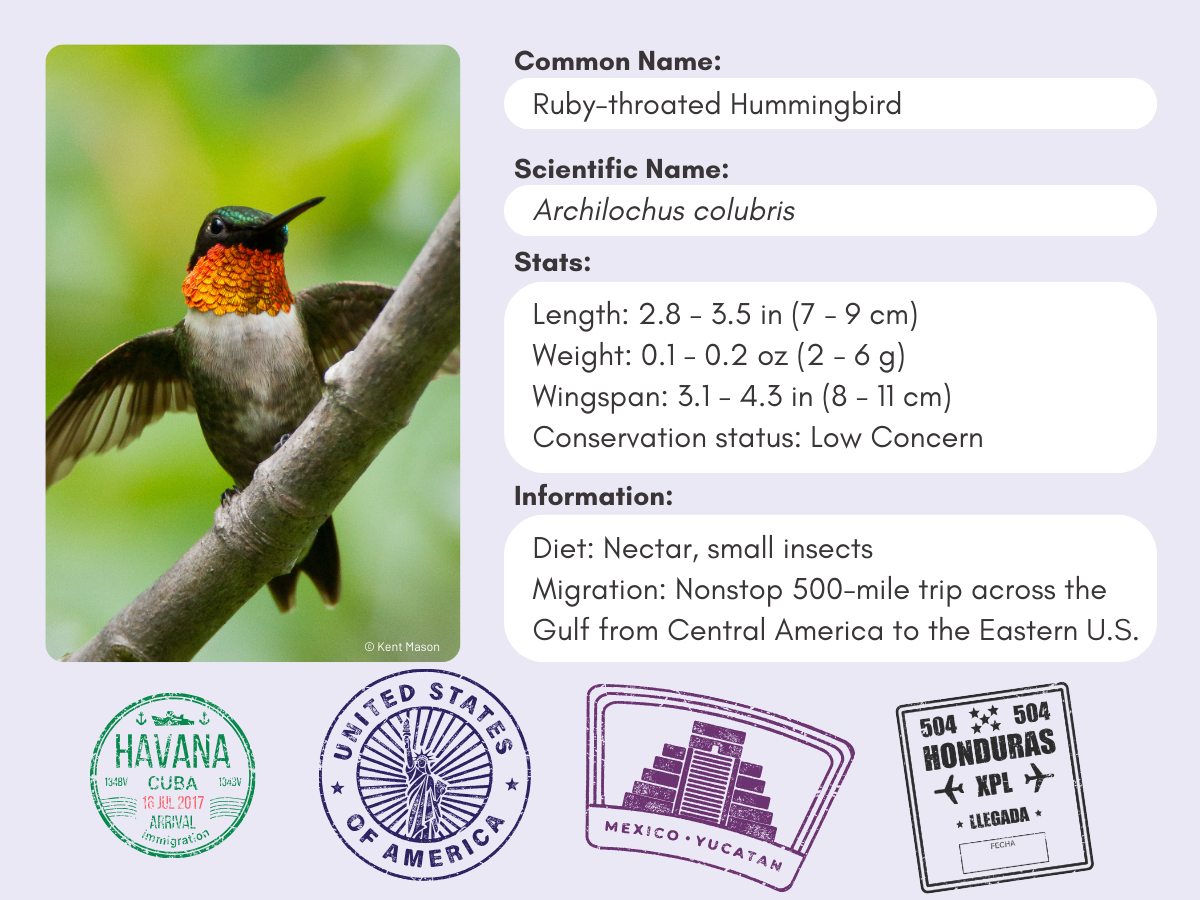

The migration of the ruby-throated hummingbird in proportion to its tiny size is a marvel of the natural world. Many of these birds make a nonstop, 500-mile trip across the Gulf from their winter grounds in Central America to the Eastern United States where they will breed and raise young. Once here, the nectar-loving birds look for bright flowers in meadows and forest edges to give them their sugar fix, but they also need to hunt small insects to provide protein and fat to help them make their yearly trip back down south.

Geoffrey A. Keller; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Ruby-throated hummingbirds most often give rapid, squeaky chips or twittering squeaks—short, mouse‑like notes heard during chases, territorial disputes or interactions at feeders. They also produce a simple, even chee‑dit call and constant wing‑humming, the latter created by wings beating up to 50 times per second. Though they do not sing true songs, their calls include a range of chirps, squeaks and fused note types that together create surprisingly complex vocal sequences.

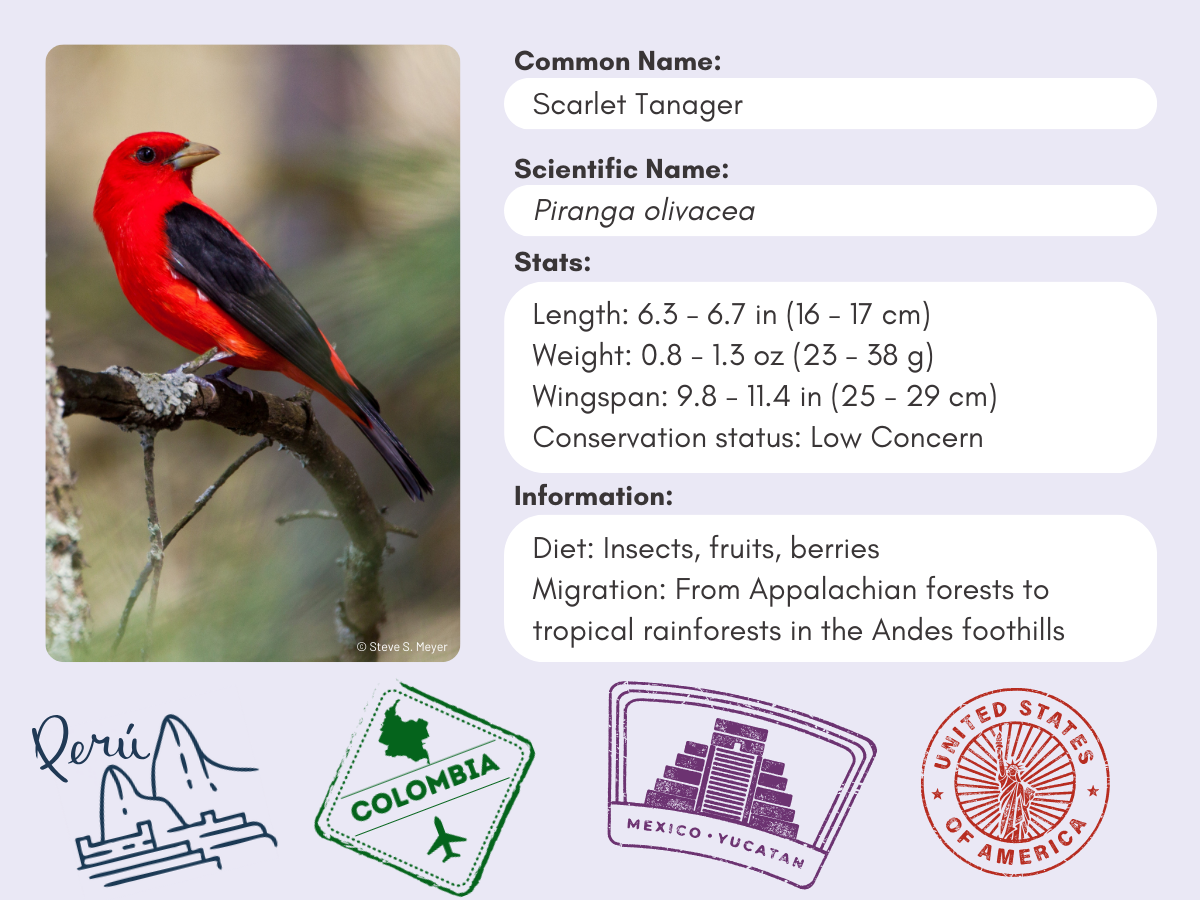

The brilliant red feathers of the male scarlet tanager are an exciting thing to spot in an Appalachian forest during the spring or summer. These bright colors help them attract mates during the breeding season, but they molt into more subdued tones when it’s time to migrate south to tropical rainforests in the foothills of the Andes where they spend the winter months. While they’re here in the U.S., tanagers can often be heard and occasionally seen in Eastern forests containing oaks and other deciduous trees.

Matthew D. Medler; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

The male scarlet tanager sings a burry, choppy series of phrases often compared to a “robin with a sore throat,” typically delivered from high perches to defend territory. Both sexes give a distinctive chick‑burr call, along with softer rising calls, twittering calls in flight or while feeding, and a harsher descending screech when confronting intruders. These bright but elusive birds are far easier to hear than see, as their sharp, buzzy calls carry clearly through dense forest canopy.

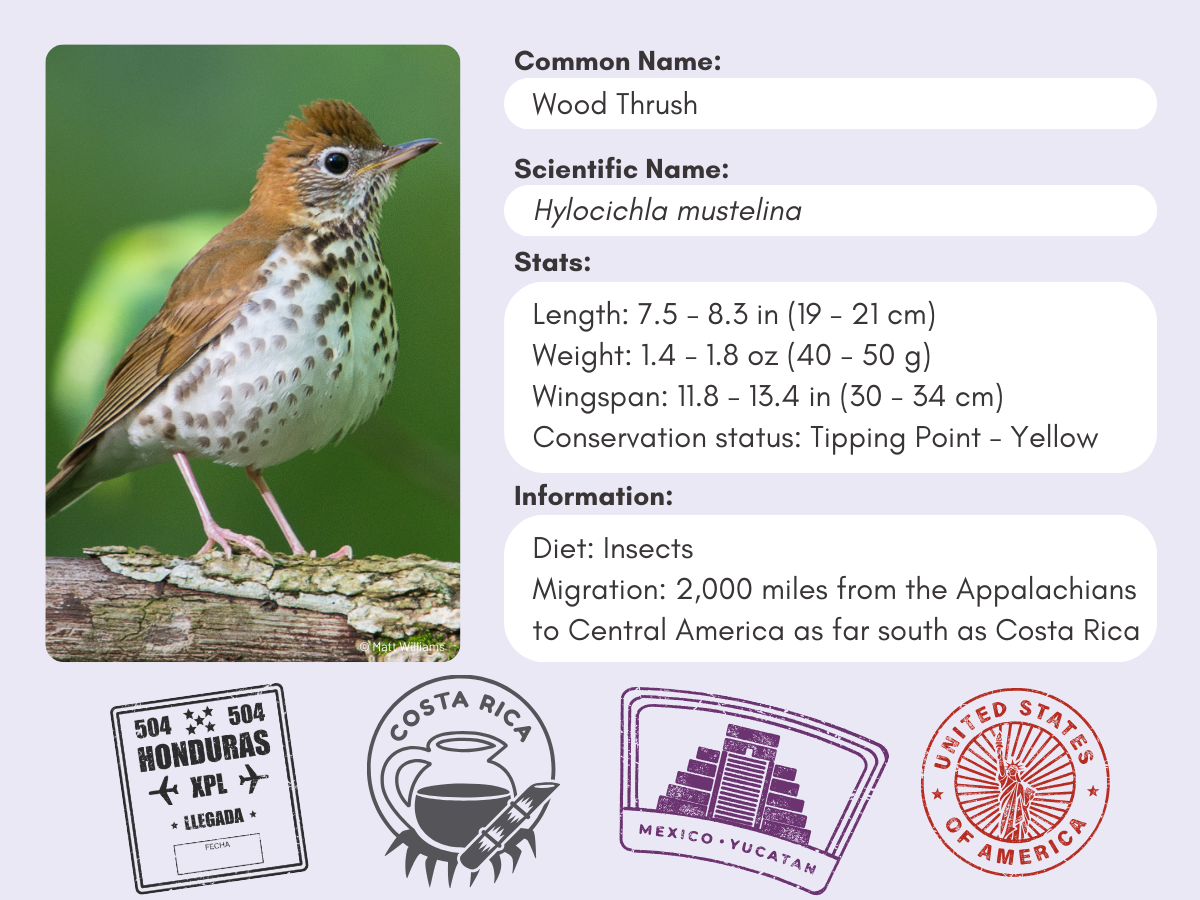

The unmistakable flute-like song of the wood thrush can be heard in deciduous forests all over the eastern U.S. in the summer. Each fall, the wood thrush leaves Appalachian forests and begins a 2,000-mile journey to Central America, venturing as far south as Costa Rica. The Appalachians play a vital role in this migration, offering mature forests where thrushes can rest and refuel on insects and berries. These same forests are critical breeding habitat in spring, making the Appalachians a lifeline for a species that has declined by more than 50% in recent decades. Listed on the IUCN Red List as Near Threatened, the wood thrush faces threats from habitat loss both in North America and its tropical wintering grounds.

Wil Hershberger; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

The wood thrush’s song is a rich, flute‑like ee‑oh‑lay, actually the middle phrase of a three‑part song that blends clear, whistled notes with an ethereal, harmonic quality created by its double voice box. Males sing numerous variants, producing more than 50 distinct songs by mixing different introductions, middle phrases and trilled endings. Its calls range from soft bup‑bup‑bup notes signaling mild distress to a sharp, rapid pit‑pit‑pit alarm during territorial or nest defense.

Migratory birds remind us that nature doesn’t abide by our manufactured human boundaries. The health of their populations relies upon a diversity of habitats across multiple continents. Here in North America, Appalachian forests are some of the biodiverse and resilient ecosystems that support a vast array of birds and other species. Nature and people rely on healthy and connected forests that provide an opportunity for species to move, migrate and adapt when necessary. But past, present and future land use threatens the health of our forests. At present, just 26% of these essential forests are under some form of protection. We must act now to protect these forests and the species that call it home before we lose what we cannot replace. The Nature Conservancy has established Appalachia as one of our highest global conservation priorities, and thanks to our dedicated supporters, we are putting together an Appalachian corridor of healthy and connected forests that benefit both people and nature.

Read more about our work in the Appalachians.