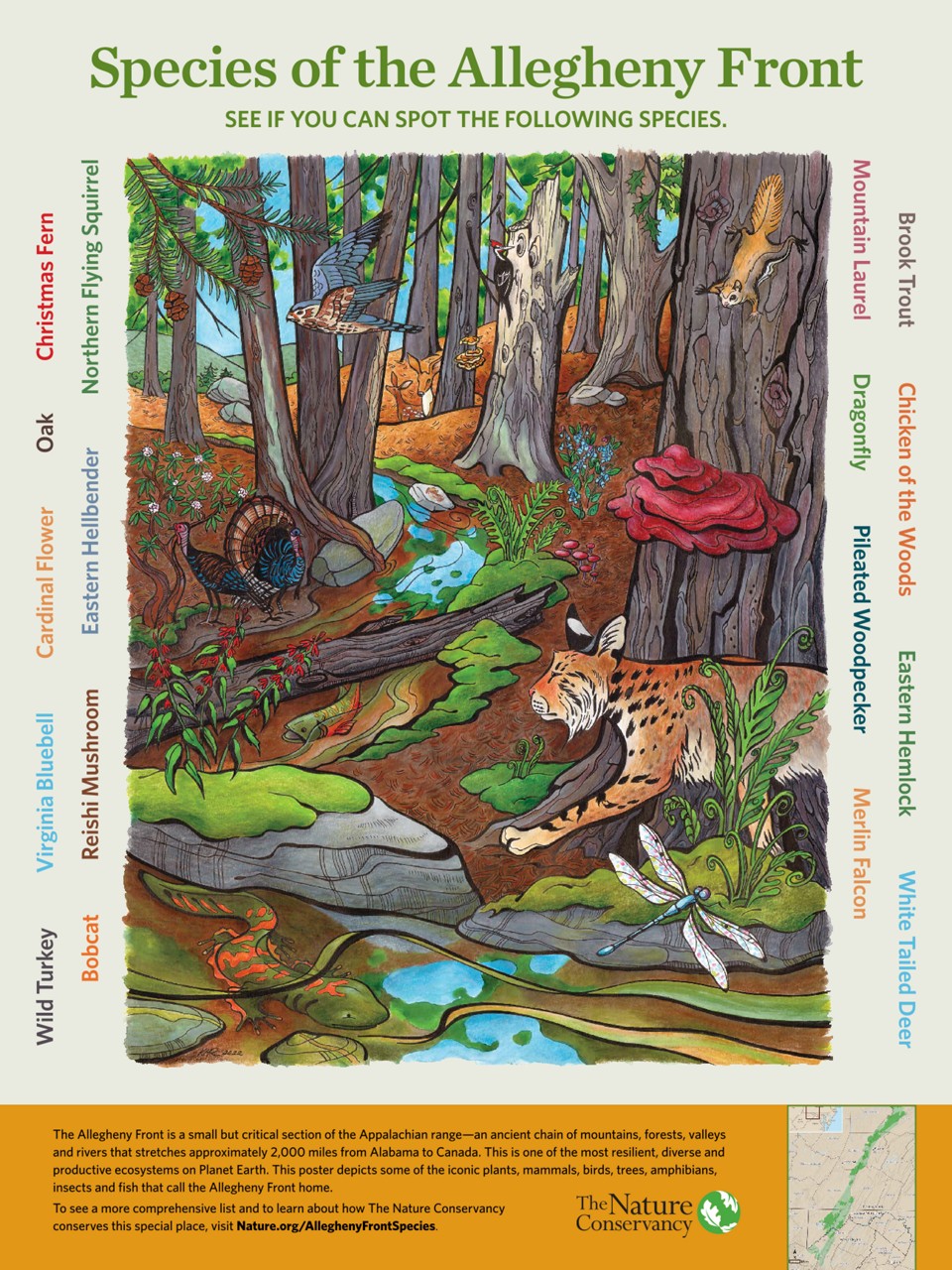

Species of the Allegheny Front

Learn more about this astonishing landscape, the species that call it home and the work that TNC is doing to conserve this special place.

More than 400 million years ago, natural forces conspired to make the Appalachians one of the most resilient, diverse and productive ecosystems on Earth. The Nature Conservancy has prioritized conservation across this ancient chain of forested mountains, valleys, wetlands and rivers as a global imperative due to the high biological diversity of species, the carbon stored in the forests and the rich history and culture of this landscape, beginning with the original Indigenous stewards.

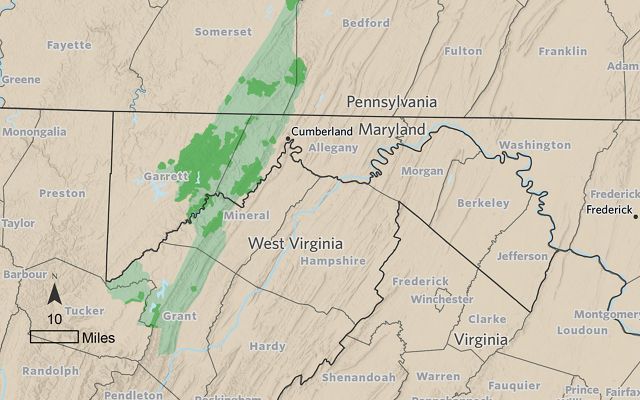

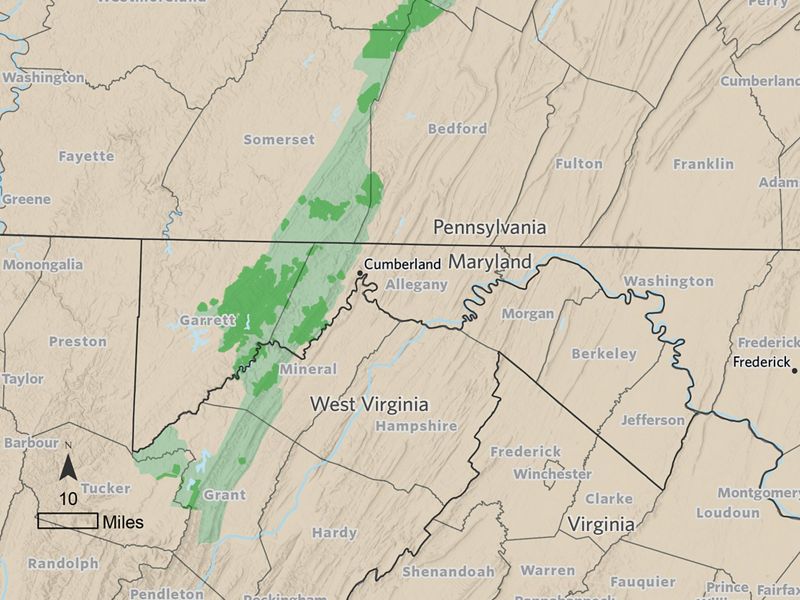

Within the 2,000-mile Appalachian range are several sub-geographies. Here in the backyard of the mid-Atlantic we have the Allegheny Front, stretching from the panhandle of eastern West Virginia, north through western Maryland and into central Pennsylvania.

Download

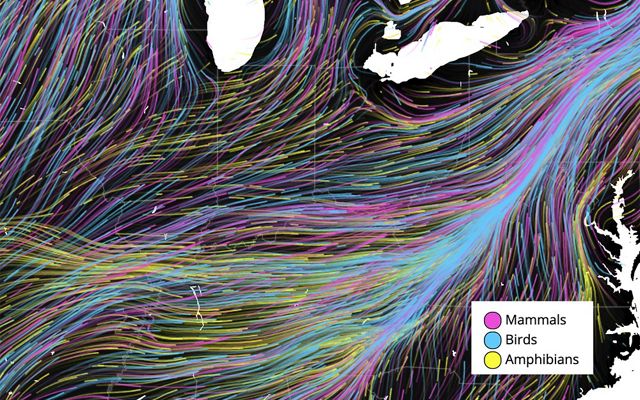

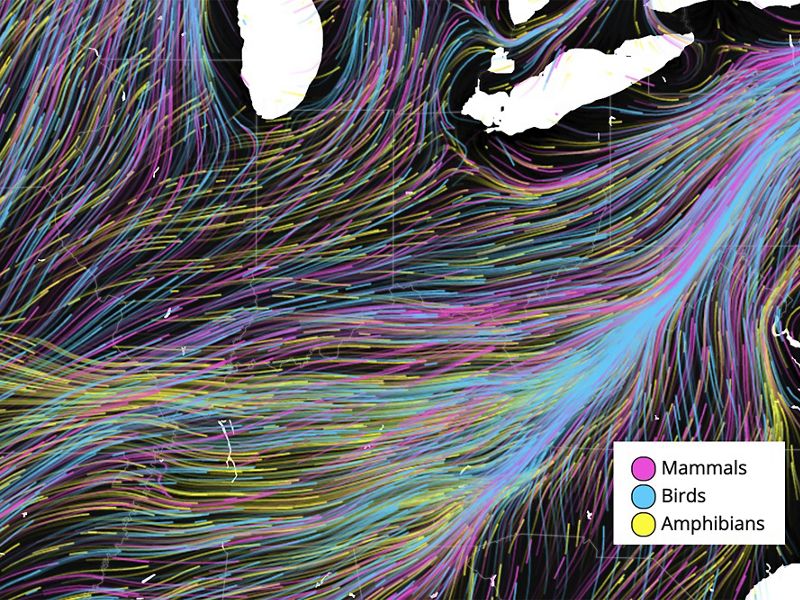

Our science has pinpointed the Allegheny Front as a priority landscape to preserve the rich biodiversity of the larger Appalachian range as climate change drives species to move and adapt. Serving as a habitat bridge between vast conservation lands in the southern and northern Appalachians, the Allegheny Front plays a critical role in keeping this continental ecosystem connected.

The forests of the Appalachians are home to a vast array of species. Nature and people rely on healthy and connected forests that provide an opportunity for species to move, migrate and adapt when necessary. But past land use threatens the health of our forests. At present, just 26% of these essential forests are under some form of protection. We must act now to protect the Allegheny Front and the species that call it home before we lose what we cannot replace.

Explore the page below to learn more about this astonishing landscape, the species that call it home and the work that TNC is doing to conserve this special place.

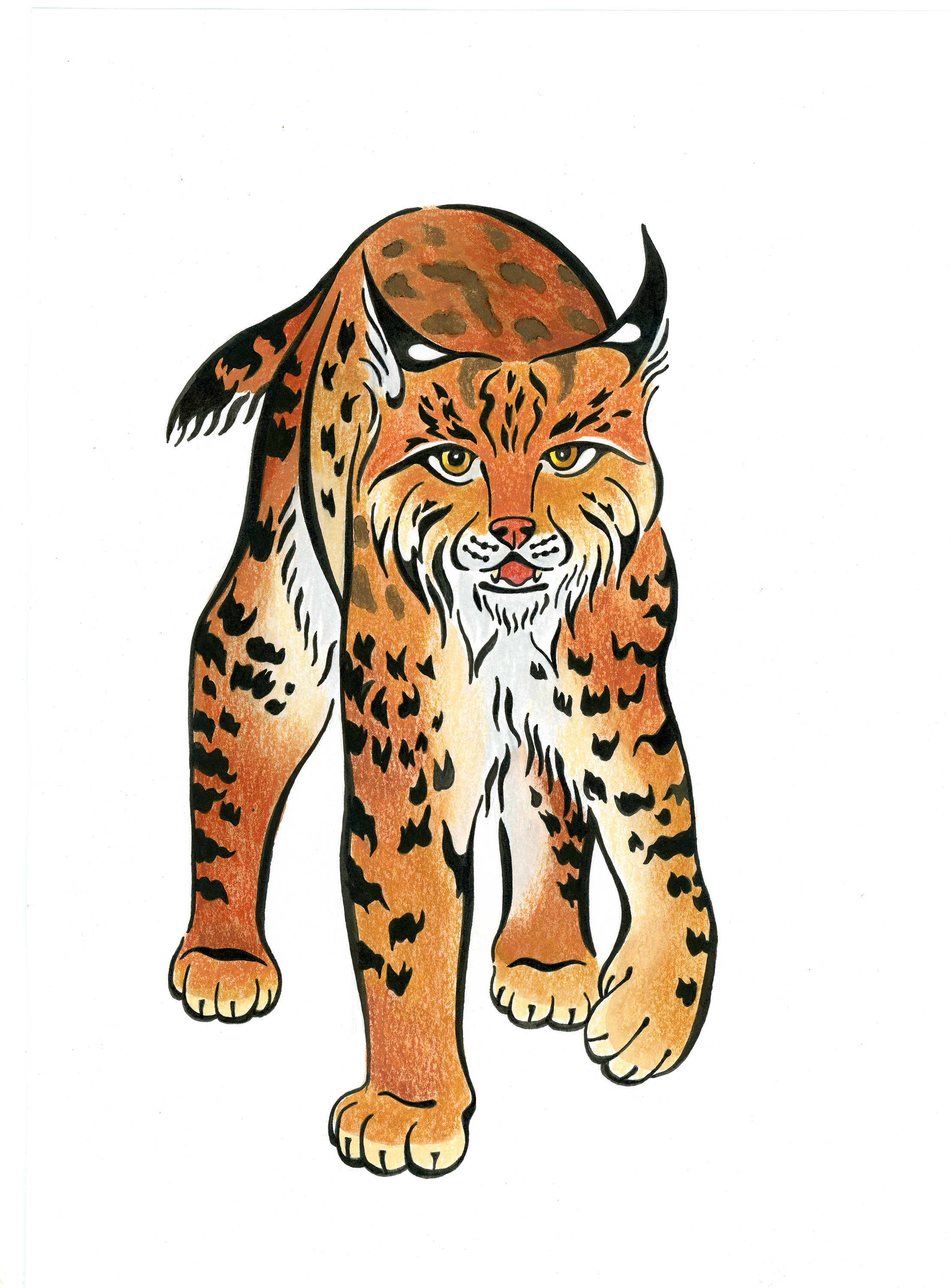

MAMMALS

BIRDS

REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS

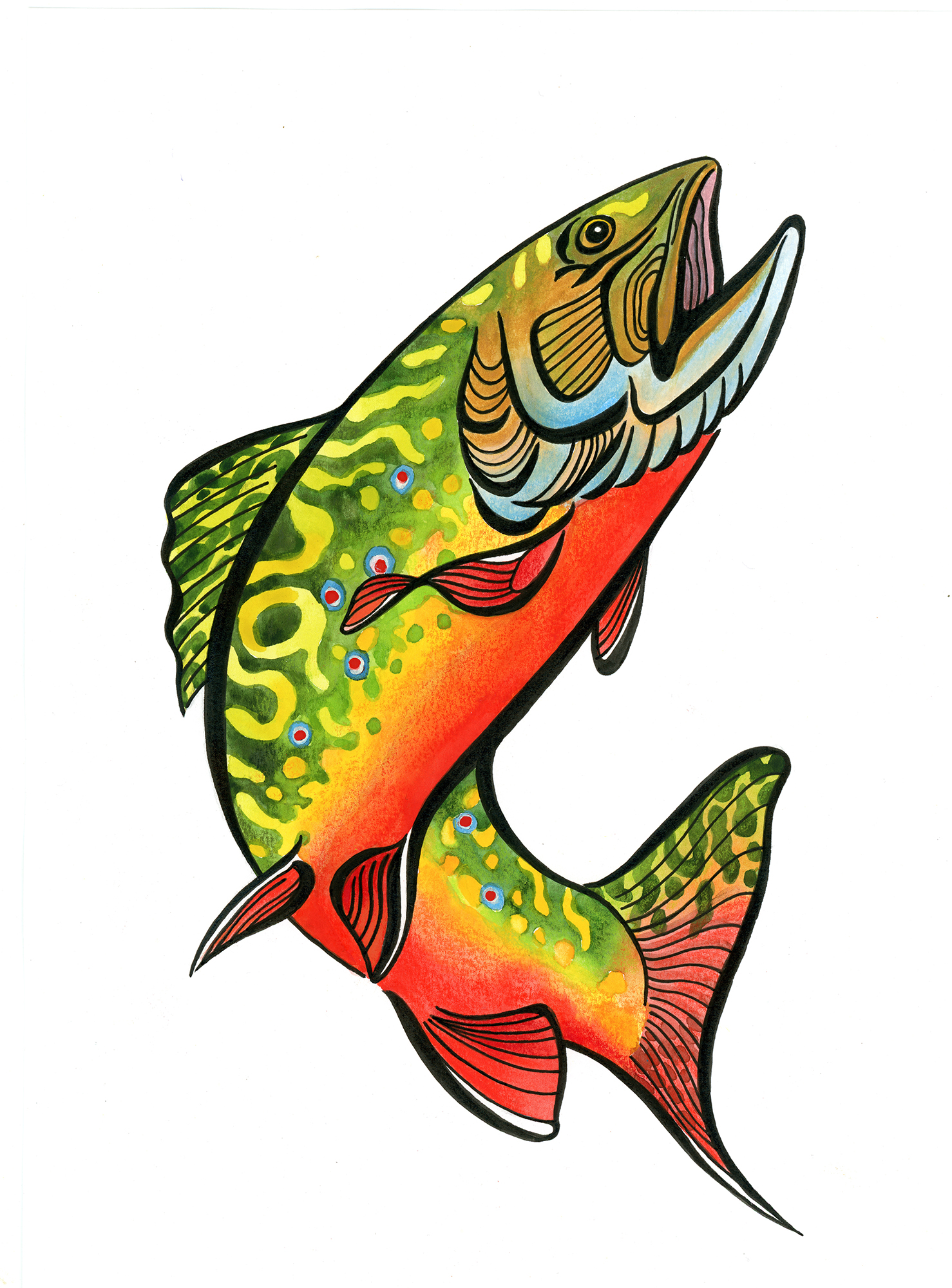

FISH

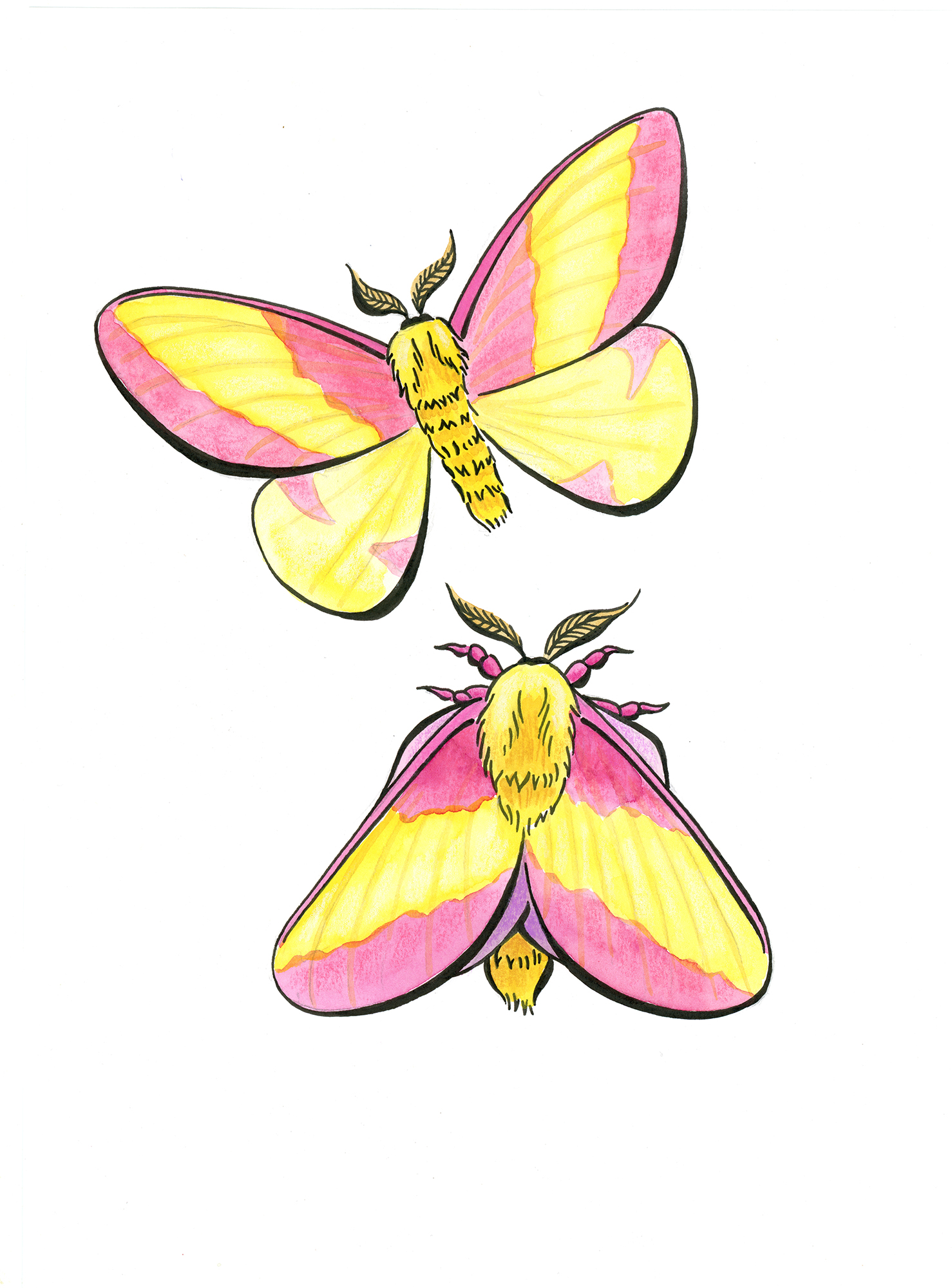

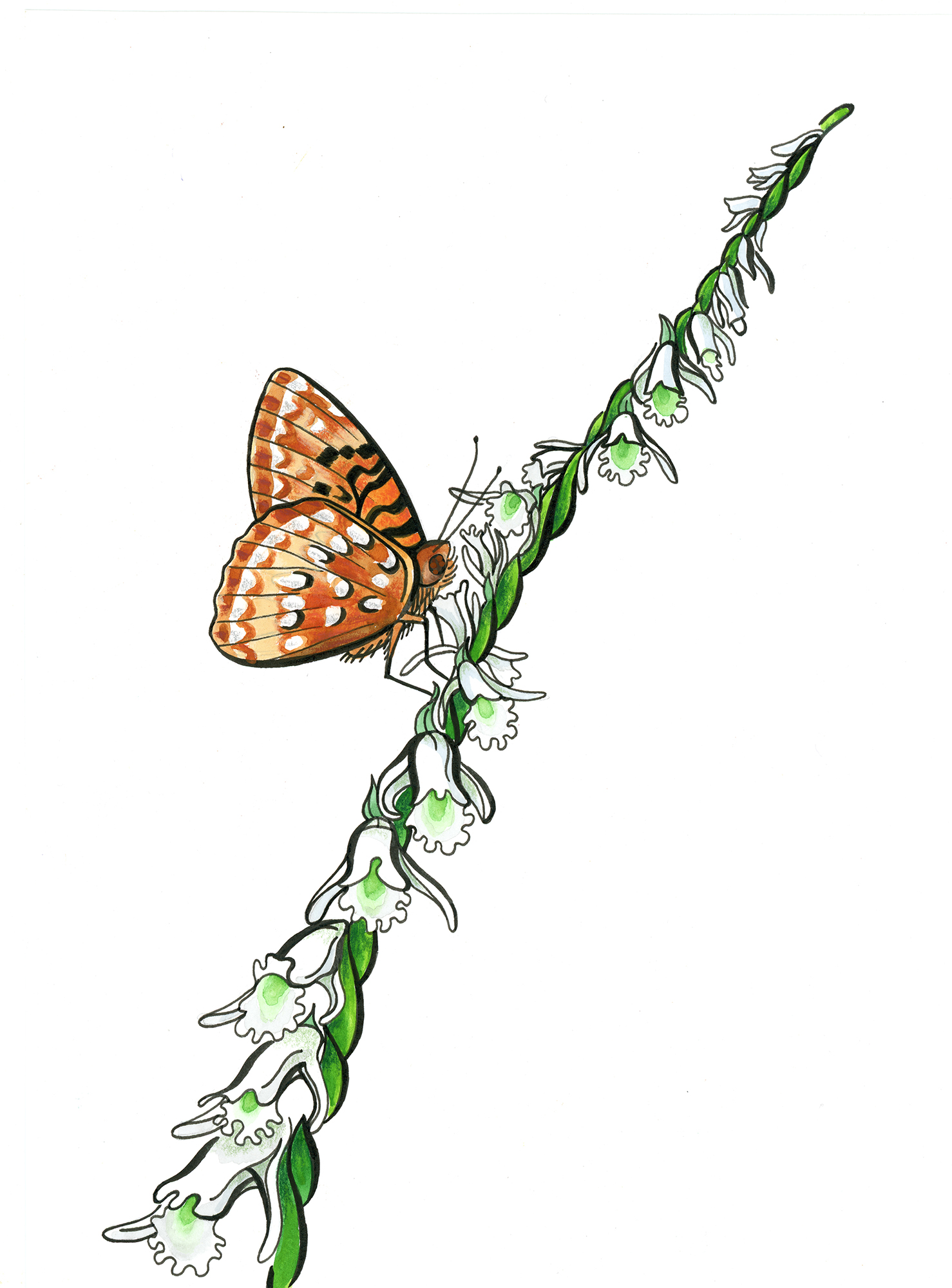

INVERTEBRATES

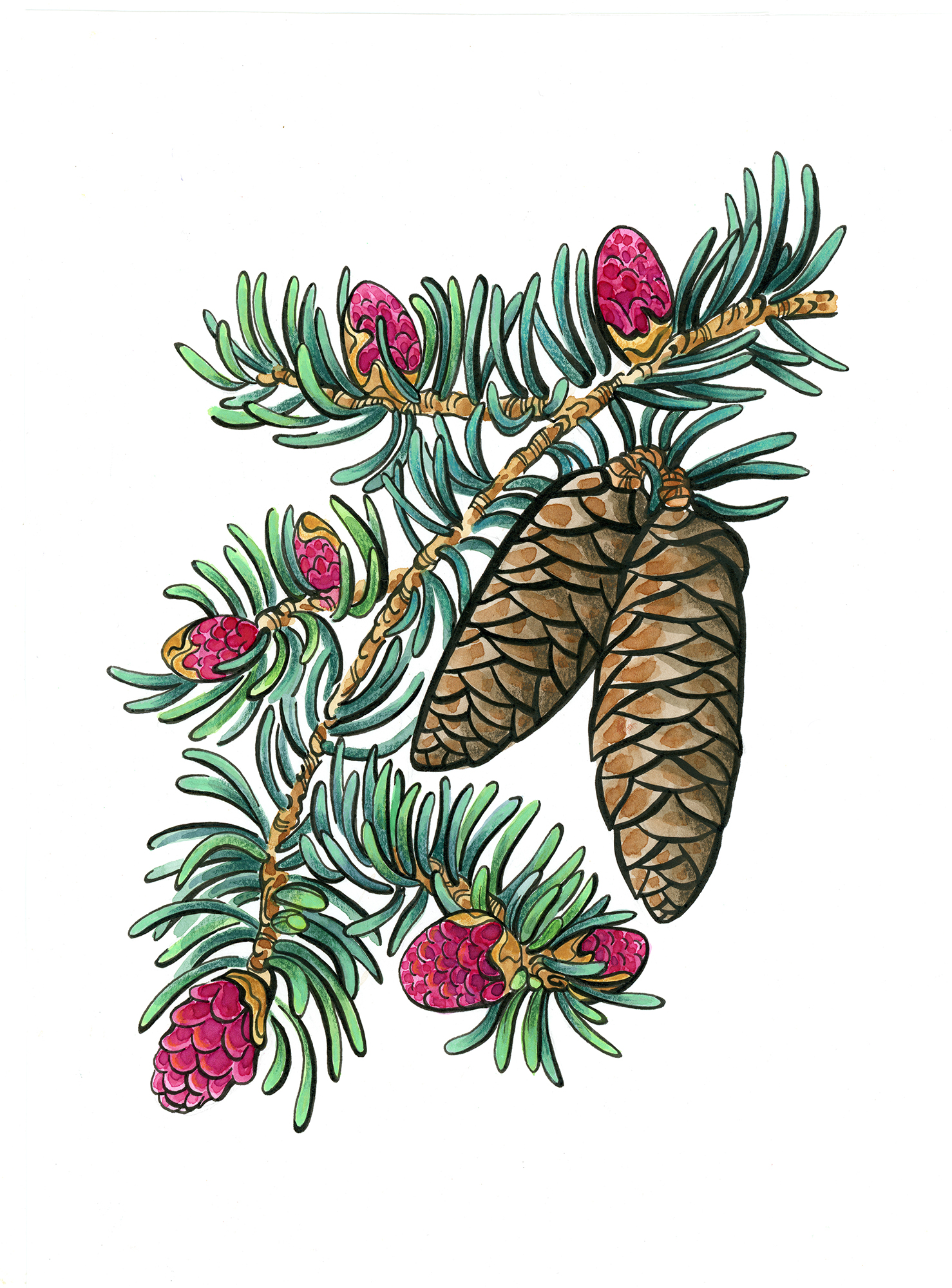

PLANTS AND TREES

Watch: Learn More

Hear from TNC experts Dr. Deborah Landau, Maryland/DC chapter Director of Ecological Management; George Guess, Pennsylvania/Delaware chapter Fire Specialist / Land Steward; and Mike Powell, West Virginia chapter Director of Land Conservation as they talk about their work and share some of their favorite Allegheny Front species in this webinar moderated by Central Appalachians Program Director Angie Watland.

Stay In Touch

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates. Get a preview of Nature News email.