Partnering with Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities

Unification of the Americas

Indigenous Wisdom and Healing at the Gathering for Mother Earth in Chile

Words by Annabelle Le Jeune and Art by Camila Peñeipil

Content Warning

This story contains discussion of genocide, slavery, racism and other scenarios of the impacts of colonization. Please take care while reading.

Growing up, Claudia Antillanca and her family foraged the coastal forests of Huiro in Chile’s Los Ríos Region. Here, they harvested timber and gathered other natural goods like seaweed, mussels, berries, flowers and more, honoring age-old traditions in preparing essentials like food, medicine and ceremonial rituals.

The Antillancas are Mapuche Lafkenche, “people of the sea,” who descend from Punta Falsa—a point so remote it doesn’t appear on a map. Like generations before her, it is the place that Claudia calls home.

The Mapuche are one of several Indigenous communities who primarily reside within regions of Chile and parts of Argentina. Their identity, wisdom and lifeways are deeply intertwined with their homeland's geography and natural systems: people of the sea, plains, valleys or other distinct landscapes.

But settler occupation and influence have largely divided, disrupted and displaced the original stewards of Chile from their land, traditions and identity. Today, the Mapuche Peoples continue to feel the effects of centuries of colonization, which exploited native species for timber, fishing and other industries, devastating both biodiversity and culture. As Claudia and her community seek healing through efforts like restoring native plants, learning their native language and gaining representation in local governance despite lasting challenges, she learns they are not alone.

At "Unification of North and South America: A Gathering for Mother Earth,” Indigenous Elders, knowledge keepers and guests, and community representatives and TNC leadership from North and South America met at the Valdivian Coastal Reserve in Chile to exchange cross-hemispheric worldviews and stories to restore balance for the land and its people. The gathering created a space to bridge Indigenous and Western knowledge systems, strengthening TNC’s role in supporting the self-determination of Indigenous and community stewards to sustainably and culturally manage their ancestral homelands. It was a crucial step in building the organization’s capacity to tend healthy, positive relationships needed to cultivate shared conservation outcomes.

TNC has set an ambitious goal to conserve nearly 1.6 billion acres (650 million hectares) of land worldwide by 2030. More than half of this healthy lands target can only be reached through meaningful partnerships with Indigenous and community rightsholders. But, for Indigenous Peoples, the 2030 goals are only a portion of the timeline. For example, in the Seven Generations principle, Indigenous wisdom urges us to make thoughtful decisions today with the past, present and future generations in mind in order to foster a sustainable world.

Take Care of Nature, Nature Takes Care of You

Perched atop a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean is a Ruka, or circular traditional Mapuche house made of wood, which Claudia and her community recently built. It’s surrounded by the Valdivian Coastal Reserve within one of the world’s largest temperate rainforests that stretches along southern Chile’s coast.

For four days, participants gathered in the Ruka and sat around the central fire to listen, learn and acknowledge: in every chair a leader. Regardless of familial affiliations, cultural hierarchy, political, economic, social class and any other labels used to divide people, individuals walked through the door as friends and family. They carried with them various ways of knowing, such as Western perspectives and ancestral wisdom, which include the spiritual teachings, values, principles and beliefs that stem from harmonious relationship with the natural world and passed down through generations.

Despite their physical distance, the Elders and knowledge keepers from Indigenous communities across North and South America mirror each other in several interconnected ways, from their origin stories and experiences of colonization to their ecosystems and customs.

Marilyn Fredricks

Marilyn, a member of the Hopi Nation, reflects on the stories her grandmother once shared about their ancestors.

I'm right now, I'm thinking about my hundred-year-old grandmother that told me all these stories from the ancestors. And she talked about the water world, which is what I'm looking at right now of the Pacific Ocean. I cannot fathom how large it is, what world that is, but we have knowledge of, of it, what it is.

And I'm just thinking, how did my grandmother know of this place when she never left her, our homelands? And she never knew the English language. How did she know? But she knew, so in, in that way, we also know, and now I see it with my own eyes. So, I know, that in some part of our DNA, our epigene, that we experienced this same place. So as soon as I got here, I was looking around and I immediately saw the flag in the same directions. The same images on that flag are actually hanging in my house. And when I saw the women, um, with their black dresses tied to the right and open to the left, um, you know, that's exactly how we dress too.

So, uh, immediate connections. And then when I went into the rainforest, as soon as we passed the gates, there was my clan totem, the bamboo, uh, reed or reed plants that greeted me as soon as I took my first step into that rainforest. So that confirmed, um, the connections that I have to this place.

And so, we're always walking backwards, looking behind us to, to our ancestors. So, um, I'm just corroborating, verifying the stories that are told to us through our oral traditions and all the Hopi footprints that we have made all over the land.

The world by the different clans that migrated to the center place where we live now. So that's the story I will take back home to them and say it is so. What our grandmothers and our great grandmothers have taught us it is the truth.

The mother-daughter duo from Southwestern Alaska, Rose and Katrina Domnick, led an interactive activity that simulated the trauma that communities like their own Yupʻik Peoples experienced. They used a model rooted in Indigenous knowledge known as calricaraq, a practice proven to end intergenerational trauma and advance individual, interpersonal and community healing.

Participants were arranged in four circles around the fireplace, which symbolized spirituality. The innermost circle enclosing the fire represented the youth and children of a community, followed by Elders, women and men, surrounded by the natural world and other non-human relatives.

“Once you acknowledge, healing can take place,” said Rose Domnick, traditional healer and Calricaraq facilitator, Yupʻik.

Each person in the four circles represent a role in the Tribal community and have a responsibility to care for each other. When the circles are intact, a symbiotic relationship ripples in which everyone depends on each other and contributes toward a thriving community.

“When contact came from the colonizers, they took away our spirituality, the thing that guided our humanity.” Rose pointed to the fire. “Then, they took our children.”

One by one, participants were selected and asked to step outside of the Ruka, leaving gaps in the circles where they once sat.

Parallel to the experience of many Indigenous communities, the Alaska Native children were forcibly sent to boarding schools, leaving the Elders with no one to whom they could pass down their wisdom. The women had no children to nurture or Elders to support, and the men were called to work far away and could not tend to responsibilities at home or keep the freezers full.

The circles, once strong and interconnected throughout the community, unraveled. Within a handful of generations in Alaska, the gaps in the communities created a decentralized family unit. As documented in the Alaska State archives, the majority of Alaska Natives went to boarding school by the age of five. The Western schools taught reading and math, but they did not teach the Yupʻik culture. They did not teach love, patience or how to be a good human being.

Though a continent apart, the Yupʻik story of colonization is all too familiar for the Indigenous participants joining from North and South America. Knowledge keepers from various Amazonian communities spoke about the enduring struggle for their peoples' survival. The Uitoto Murui tribe of Peru, in particular, suffered gravely during the rubber boom that took place between the late 1800s and early 1900s. This marked one of the worst humanitarian crimes in the Amazon, involving genocide, slavery and exploitation of natural resources.

Colonization severed the social fabric and holistic connection of Indigenous Peoples and their lands, which were exploited and left unfertile. Plants, vital for both physical and spiritual well-being, were depleted. Language, songs, dance and other cultural customs passed down from generation to generation were lost.

Though these truths remain raw and bear the pain and weight of the loss of life and culture, the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon still find strength to speak up and seek justice to care for their homelands in their self-determined ways.

We have to tell these stories to recover those lands, said a Kichwa Kayambi knowledge keeper from Ecuador. They shared that wearing red is a cultural custom when traveling to other territories because it is a protective color: red remembers all the people who died so we never forget. The land is looking for balance.

"Lo más especial de este bosque es la energía que nos entrega. De una forma más científica, cuando hace demasiado calor, como hubo hace dos días atrás, se produce un efecto que termina haciendo que llueva, como hoy día, y regula las temperaturas. De una forma más sentimental, yo para llenarme de energía voy al bosque y abrazo un árbol. Este territorio es bien bendecido porque alcanzamos a protegerlo."

The most special thing about this temperate rainforest is the energy that it gives us. In the scientific way, when the forest is too hot, like it was the past few days, it rains to regulate the temperatures. In a more sentimental way, to fill myself with energy, I go to the forest and I hug a tree. This territory is very blessed because we have been able to protect it.

—Danilo González Huala, Mapuche, Vadivian Coastal Reserve Park Ranger Coordinator

But that protection was only made possible by the tenacity and perseverance of its dwellers.

In those times, the Indigenous communities lived in harmony with their homelands, until the land was sold to a logging industry. Then, the exploitation of the native forests were decimated by Eucalyptus plantations spanning thousands of acres (equivelant to thousands of hectares), causing irreversible harm to the biodiversity and communities that once thrived in balance with nature. The company evicted the community by relocating the families to more remote areas, where they live today.

Claudia recalls a vivid memory from the age of four when her family helplessly witnessed the destruction of their home: “Cuando estábamos en casa del abuelo, vimos arder nuestro hogar—la naturaleza— junto a todos los amigos del bosque: las aves, el puma, los pudúes, la guiña y todas las especies de la flora y fauna quedaron bajo las llamas y el humo negro, que permaneció por meses ahí. Llore de pena y tristeza por mis amigos y cada día que pasa, pienso que tengo una gran misión, el conservar la naturaleza, de todo invasor que quiera destruirla.” When we were at grandpa's house, we saw our home—nature—burning, along with all the friends of the forest: the birds, the puma, the pudúes, the guiña and all the species of flora and fauna were under the flames and the black smoke, which remained there for months. I cried with sorrow and sadness for my friends and every day that passes, I think that I have a great mission, to conserve nature, from any invader who wants to destroy it.

The loggers found what the Mapuche have always known: the value of the Alerce tree is nearly unparalled. Its lightweight and durable wood is resistant to rot, water and fire, making it ideal for longstanding building traditions. But, they are slow growing trees with life spans of up to 4,000 years, reaching heights of more than 150 feet (45 meters) and diameters up to 10 feet (3 meters).

The foreign- and Chilean-owned forestry companies used controlled forest burning to maintain Alerce trees, clear out less revenue-generating native plants, and make space for faster-growing, economically valuable timber like the highly invasive Eucalyptus trees. A few years of forest burning that occurred over 20 years ago wounded the lands enough to require an extensive conservation process with a considerable amount of time and resources to recover.

The extractive forestry practices left the land vulnerable to invasive species, pushing the native plants further into the forest and making them harder to access. Plus, the runoff from forestry activities polluted or changed the waterways of the forests and the ocean, threatening the health of the fish and marine life—vital food sources for the community.

Danilo González Huala

Danilo speaks about the transformation he witnessed growing up around his homelands surrounding the Valdivian Coastal Reserve.

Pasaba los veranos aquí y vi cambios, muchos cambios. Porque en los veranos de mi niñez no había eucaliptus, pero volvía después de trabajar en los barcos, cuando estaban las forestales, y veía el bosque quemado y me tocó estar en el momento en que quemaron los bosques.

Entonces, cuando tuve la oportunidad de entrar a la Reserva, era, o ahora está la posibilidad de poder cuidar el territorio y poder, quizás, con la idea que aún tenemos, de poder recuperarlos, quizás no para nosotros ni para nuestros hijos, probablemente tampoco para nuestros nietos, pero para los que vengan a futuro puedan volver a ver los bosques que nosotros veíamos, que jugábamos, que recolectábamos. Y creo que ese es mi mayor vínculo con el proyecto.

Primero fueron cambios muy radicales cuando llegaron las forestales, porque conocíamos los bosques que hoy día recorrimos, eran, estaban abajo donde hoy día hay eucaliptus. Grandes árboles, con muchas aves. Teníamos muchos animales al lado, mucho, mucha planta medicinal.

Luego, cuando comienzan a llegar las forestales en el año ‘86 -yo había salido de estudiar y me había venido para donde mis padres- y comienzan a llegar las primeras empresas forestales al lugar.

No había puente. Nos prohibieron el paso hacia este sector, Huiro quedó aislado. Y nosotros somos todos familia, entonces, nos costaba.

Y luego fue peor cuando quemaron las montañas. Porque aún no sabíamos, veíamos que cortaban los árboles, pero no sabíamos qué era lo que lo que pasaba, qué venía. Teníamos idea, pero jamás pensamos lo que hoy día vemos.

Entonces, se produjo ese cambio en el bosque, pero también se empezaron a producir cambios en el mar. En el río, en la costa. Comenzaron a morir los productos del mar. Mi familia estaba muy ligada al mar, entonces vimos esos cambios demasiado bruscos.

Y ese cambio nos tocó muy fuerte. Nos pegó muy fuerte porque, si bien es cierto, no estábamos relacionados al bosque y no veíamos el cambio que se iba a producir; con las aguas, por ejemplo, el cambio del mar; que fue mucho más rápido, murieron muchos productos en el mar, nos llevó a buscar soluciones.

Y como dirigente de la pesca artesanal en esos años, yo intentaba de buscar soluciones siempre, conversando, siempre dialogando y llegando a acuerdos. Pero había otro grupo de la comunidad, que era muy confrontacional, y produjo estos cambios más rápidos, y que fueron, al final fueron muy positivos para que pudiese llegar TNC al lugar.

I spent the summers here and saw changes, many changes. Because in the summers of my childhood there were no eucalyptus trees, but I returned after working on the ships, when the forestry companies were there, and I saw the burned forest and I was there at the moment when they burned the forests.

So, when I had the opportunity to enter the Reserve, it was, or now there is the possibility of being able to take care of the territory and perhaps, with the idea that we still have, to be able to recover them, maybe not for us or for our children, probably not even for our grandchildren, but for those who come in the future to be able to see the forests that we saw, that we played in, that we collected from. And I think that is my greatest connection with the project.

First, there were very radical changes when the forestry companies arrived, because we knew the forests that we walk through today, they were down where there are eucalyptus trees today. Big trees with many birds. We had many animals nearby, many medicinal plants.

Then, when the forestry companies started arriving in 1986 - I had finished studying and had come to where my parents were - the first forestry companies started arriving in the area. There was no bridge. They prohibited us from passing through this sector, Huiro was isolated. And we are all family, so it was hard for us.

And then it was worse when they burned the mountains. Because we still didn't know, we saw them cutting down the trees, but we didn't know what was happening, what was coming. We had an idea, but we never thought we would see what we see today.

So, that change happened in the forest, but changes also started happening in the sea. In the river, on the coast. The sea products started dying. My family was very connected to the sea, so we saw those changes, which were too abrupt.

And that change hit us very hard. It hit us very hard because, although we were not related to the forest and we didn't see the change that was happening with the waters, for example, the change in the sea, which was much faster, many sea products died. It led us to look for solutions.

And as a leader of the artisanal fishing in those years, I tried to find solutions always, conversing, always dialoguing and reaching agreements. But there was another group in the community that was very confrontational, and they produced these changes more quickly, which were, in the end, very positive for TNC to come to the place.

When a forestry company went bankrupt in 2003, TNC purchased nearly 150,000 acres (60,700 hectares) of what would become the Valdivian Coastal Reserve at a public auction. Although TNC had more than 70 years of experience in acquiring and protecting lands in the U.S., this was its first global land purchase. The vast Chilean rainforest presented a significant milestone for the organization, but managing global land brought new challenges and valuable lessons.

Initially, TNC worked with an external company to hire park rangers. While they were experts in natural resource management, they did not fully address the unique needs of the Valdivian Coastal Reserve. The interconnected systems within and around the Chilean temperate rainforest require a holistic approach to conservation.

Soon after, new management plans shifted to consider the environment in its entirety, incorporating all the edges of the territory with a comprehensive conservation strategy that honored both scientific and traditional knowledge, such as the place-based skills, practices and customs developed over time. From the forest plants to the ocean fish, farm cattle and local people, these systems are interdependent—they coexist. When the forests suffer, the rivers suffer; when the people thrive, the ecosystem thrives.

Indigenous & Community Leadership in Conservation

When Indigenous Peoples and traditional communities have rights and resources to care for their lands, waters and well-being, nature—and the life it nurtures—thrives. Biodiversity is richer and more resilient. Carbon is stored in forests, grasslands and coastal ecosystems. Communities flourish with healthy food, clean water, meaningful livelihoods, and diverse cultures and traditions that honor past, present and future generations.

Learn more about how TNC partners with Indigenous and community stewards globally to advance conservation in some of the planet’s most vital ecosystems.

TNC hired community members like Claudia and Danilo who carry much more than their inherent knowledge of the region’s environment. They have a deep connection and understanding of the historical, political and cultural context of their Mapuche homelands; they know how to respectfully liaise the sometimes-complex sensitivities of natural resource management.

Today, the Valdivian Coastal Reserve models how reciprocal stewardship yields shared conservation outcomes when Indigenous and community leadership is centered. TNC supports the wellbeing of the temperate rainforest, its surrounding environment and people through authentic partnerships with the Mapuche communities, local fishing villages, farmers, restaurants, the tourism industry and more—all in an effort to promote the co-management of the lands and waters to ensure its conservation.

At over 100 feet (30 meters) high and nearly 9 feet wide (2.7 meters), Abuelo Alerce stands the test of time, bearing witness to a checkered history of both familial and foreign faces. He is a relative of the Mapuche Peoples, a true living link between their ancestors past and their future generations.

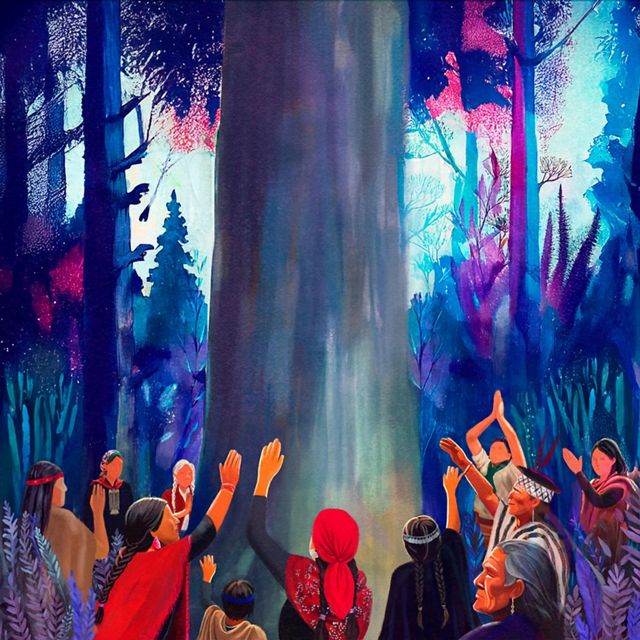

The Indigenous Elders, knowledge keepers and guests from North and South America linked hands and formed a large circle around Abuelo Alerce. They tilted their heads back to look up at the Elder tree standing tall toward the skies above as they sang and danced. And like Abuelo Alerce, they stood tall and unified with a message to the world: "We are still here."

Indigenous Wisdom for Mother Earth

Claudia sat across the fireplace of the Ruka, when a spiritual leader from a neighboring territory said, you have a huge forest of medicine here in the Valdivian Coastal Reserve, take care of them.

The Valdivian temperate rainforest boasts a thriving population of the endemic Canelo tree (Drimys winteri)—one of the most sacred plants for the Mapuche, used for medicine and healing, rites of passage, ceremonies and protection, and more.

Calfin Lafkenche

Calfin shares that the Mapuche honor the land as interconnected with people and spirituality.

Por eso es que la Reserva, al igual que el Parque Nacional Villarica, Huilo-Huilo, para nosotros son importantes, porque son los espacios principales donde hoy día encontramos la medicina. El decreto 701 de la ley forestal favorece los mono-cultivos, entonces eso nos afecta un montón.

Y así, por eso que los mapuche, defendemos los territorios, no porque es tierra, porque nuestra espiritualidad de nuestra familia ancestralmente está ligada al territorio. Entonces nada puede pagar la tierra que una empresa me quiera comprar. Cuando nos obligan a partir o quieren hacer represas y quedan todos, los cuerpos de nuestra gente bajo tierra, ese es un dolor y nosotros nos enfermamos. Y por eso es que luchamos por mucha salud con nuestra lucha política.

Porque si no hacemos lo que fuimos mandados a hacer, nosotros nos vamos a enfermar y enfermamos toda nuestra descendencia.

That is why the Reserve, like the Villa Rica, Huilo-Huilo National Park, are important to us, because they are the main spaces where we find medicine today. Decree 701 of the forestry law favors monocultures, so that affects us a lot.

And so, that is why we Mapuche defend the territories, not because it is land, because our spirituality of our family is ancestrally linked to the territory. So nothing can pay for the land that a company wants to buy from me. When they don't force us to leave or want to build dams and all the bodies of our people are left underground, that is a pain and we get sick. And that is why we fight for good health with our political struggle.

Because if we don't do what we were told to do, we are going to get sick and all of our descendants will get sick.

Many teachings and wisdom of Indigenous Peoples around the world predicted a time when Mother Earth will teeter on the brink of imbalance and signal for us to reset with ourselves, each other and our natural systems. Inspired by these prophecies, TNC honors the original and best stewards of the lands and waters as a way to achieve shared conservation outcomes and address the climate change and biodiversity loss crises.

The "Unification of North and South America: A Gathering for Mother Earth" marked a milestone in TNC’s path to transform its conservation approach. Yet, it illuminated the need to continue its learning journey of listening and honoring spiritual, place-based knowledge that is vital to shift conservation practices in a good way.

Elevating Indigenous and community leadership in conservation is about listening to the needs of Mother Earth, it’s about supporting self-determined rights and sovereignty, it’s about moving slow to move fast, it’s about healing both the people and the land.

It’s about protecting the spaces we love so that the current and future generations can continue to practice the traditions their ancestors once did, and the way their children and their children’s children deserve to do.

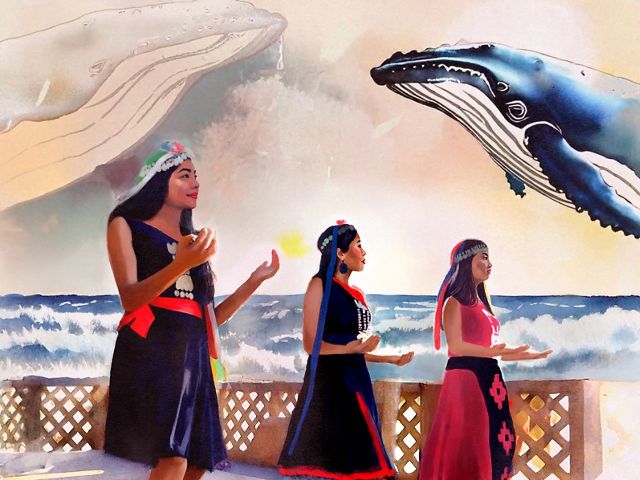

Set against the backdrop of the Chilean temperate rainforest, the setting sun cast a fiery glow on the ocean behind the young dancers, descendants of the Antillanca family. They wore their traditional regalia and danced with pride as they welcomed guests from North and South America to the Valdivian Coastal Reserve—home.

What is something Mother Earth is asking for?

Participants at the Unification of North and South America Gathering in Chile weigh in on what the planet needs right now.

Ruchatneet Printup, Tuscarora Haudenosaunee Confederacy (New York): "When you look at it from the perspective of a mother... she's looking to be taken care of, and to be honored, and to be thanked, and that you spend meaningful time with. Just like a mother wants for her own children, that she has that kind of relationship with them.”

Marylin Fredericks, Hopi (Arizona): “What she is asking of us is to remember this gift of life and not to squander it, not to be careless, to be mindful of everything that we do and how it is. How she cares for us, we should care for ourselves and our children.”

Carrie Franco, Yowlumne Yokut (California): “Keep praying, keep offering, and keep making offerings in the morning, in the night, afternoon, when the sun's high noon, that's a good time because that sun is just right there to go make an offering... So, I tell everybody: keep making offerings. The Earth's, it's just going to do what she'd been doing for millions and millions of years, and there's nothing we can do about it, except walk good, walk in beauty, walk in prayer. Take care of her best way we can.”

Lonco Cristian Orlando Lemunao Yancamán, Mapuche (Chile): “Siempre la Madre Tierra está pidiendo que la respetemos, que no nos olvidemos que la Madre Tierra nos da vida, que nosotros somos parte de ella, que si ella no nos diera alimentos nos nos acompañara, nosotros no estaríamos, es como lo principal. Nosotros acá como Mapuche hemos cometido ese grave error. O sea, por como está la vida hoy día, por la tecnología, por la ciencia, también hemos pecado de olvidarnos un poco de la tierra, porque la tierra en nuestra madre, nuestro todo.”

Mother Earth is always asking us to respect her, to not forget that Mother Earth gives us life, that we are part of her, that if she did not give us food, did not accompany us, we would not be, that’s the most important thing. We here as Mapuche have made a grave mistake. I mean, because of how life is today, because of technology, because of science, we have also sinned by forgetting a little about the earth, because the earth is our mother, our everything.

Rosendo Gualima Padilla, Movima (Bolivian Amazon): “ La Madre Tierra está esperando ser escuchada.”

Mother Earth is waiting to be heard.

About the Artist

Camila Peñeipil is a Mapuche intercultural designer and illustrator. Her academic and professional journey is diverse, with a strong focus on interculturality and the integration of art within graphic design. From a young age, Camila has been deeply captivated by visual language, which inspired her to explore the symbols and colors of her Mapuche heritage. This fascination, combined with her strong ties to various Mapuche communities, has enabled her to develop a distinctive and striking visual style.

Sign Up for E-News

Helpline

It’s important to speak up when something does not look or feel right. If you have a concern about suspected violations of TNC's Policies and Procedures, laws and regulations, or behavior not aligned with TNC's Values or our Code of Conduct, make sure you tell someone about it.