Will We Choose to Save the Great Salt Lake?

In this three-part series, we’ll explore the complex story of a natural wonder whose fate will be decided on our watch.

By Larisa Bowen, Senior Writer/Editor, Western US and Canada Division

Great Salt Lake is a bellwether for the fragile future of water in the arid West. It’s a weighty new role for a saline lake that for decades had largely been an afterthought, or a kind of sideshow curiosity. Of course, scientists and conservation groups had long championed the lake’s values, but only when its demise felt imminent in 2022 did Great Salt Lake really strike a public nerve. That fall, the lake’s water levels dropped to a new recorded low, depleted over decades by increasing diversions to accommodate the growing demands of cities, industry, and agriculture upstream. A changing climate and frequent drought years added to the crisis.

In its conspicuous decline, Great Salt Lake garnered what was long overdue: public alarm, new scientific studies, national (even international) headlines and the interest of policymakers. That’s because, faced with the lake’s loss, all of us became painfully aware of the many vital roles it plays—from biodiversity to air quality to Utah’s economy.

Then, soon after the lake hit its low point, Mother Nature delivered a reprieve: one year of record-breaking snowfall followed by an above-average year of snowfall. The winters of 2022 and 2023 were a boon—but not a solution. Water levels for the lake have risen, but they remain below a healthy range for this complex ecosystem. What’s more, Utah still faces a stark reality: growing demands, limited water supplies and dire climate change predictions. The good news is that the lake’s identity has been forever changed. A brush with “collapse” has elevated Great Salt Lake to its deserved celebrity status, and there’s no going back. Many Utahns—from diverse backgrounds—are keenly aware of why they need and want this vast inland sea to persist. The question has now become whether and how our state can deliver a future in which Great Salt Lake thrives.

For The Nature Conservancy (TNC), this is a pivotal time. Momentum is continuing, alliances are growing, recent strategies are being implemented, and new ideas are taking shape. Back in 1984, TNC was the first private conservation organization to protect the lake’s vital wetlands. In the decades since, we’ve maintained a long and enduring commitment to the health of the entire lake ecosystem. Today we are thrilled to be joining a suite of partners working together in new ways to safeguard the lake’s future. Most importantly, alongside National Audubon Society, TNC co-founded and is co-managing the Great Salt Lake Watershed Enhancement Trust, an unprecedented effort funded by the State of Utah to directly help address the lake’s decline.

No solution for Great Salt Lake will be easy or fast. It took a long time for the lake to decline, and it will take a long time to recover, but the lake’s importance demands our patience and enduring devotion. Great Salt Lake has become the compelling “face” of a state that stands at a precarious crossroads for people and nature. In this era of climate change and compromise, the eyes of the West—and the world—remain on us.

Stay up-to-date with conservation near you!

Sign up for our monthly newsletter to receive conservation updates, opportunities to get involved and more.

Part 1: Nature’s Warning

Desiccation Under Our Noses

How did we even get to a place where Great Salt Lake dropped to record lows? It took time, and it wasn’t glaringly obvious. Change has always been Great Salt Lake’s specialty. The lake is dynamic (and, as a whole, much saltier than the ocean) because it has no outlet. Fresh water from the Bear, Weber, Ogden and Jordan rivers feeds into the lake, but no water flows out. As water evaporates, salt and minerals are left behind. The lake is also vast but shallow. Stretching 75 miles long and 35 miles wide, it reaches only 33 feet at its deepest points. A remnant of a prehistoric Lake Bonneville, the Great Salt Lake is spread thinly across the bottom of this ancient basin, and it is constantly “breathing”—reacting to wet and dry years by filling up and expanding and then evaporating and receding.

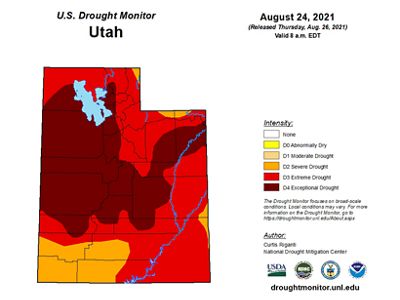

Utah is one of the driest states, so precipitation here is always precious. Yet with all the variable wet and dry years of Utah’s past, one constant has emerged: the state’s population growth and its increasing demands for water. One of the fastest growing states in the nation, just since 2000 Utah has added more than 650,000 people. To feed the growing needs of cities and agriculture, more and more water is diverted before it reaches the Great Salt Lake.

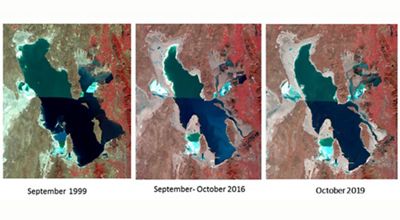

In 2017, Wayne Wurtsbaugh, a professor emeritus of watershed science at Utah State University co-published a groundbreaking paper in Nature Geoscience. His data showed that since the arrival of the 19th-century pioneers, there has been a persistent reduction in the water supply to the lake, decreasing its elevation by 11 feet, decreasing its volume by 48 percent and exposing approximately 50% of the lakebed. 2022, the problem had worsened. That fall, the south arm of the lake dropped to 4,191.3 feet—the lowest water level on record.

“For years, this complex system has been functional and resilient,” says Marcelle Shoop, who is the Director of the Saline Lakes Program for the National Audubon Society. “We’re just now reaching the point where growth, water demands, and climate change could truly threaten that resiliency and lead to irreversible consequences.”

Utah’s growth trend is not likely to slow, and Shoop explains it has been joined by another, even more daunting trend: climate change. Despite the fact that Utah enjoyed remarkably wet years in 2023 and 2024—this type of precipitation will not continue. Predictions for hotter and drier years ahead mean the lake is at risk for further decline. Shoop notes Great Salt Lake’s plight is not unique. She points to a 2017 Audubon study that revealed: “Nearly all saline lakes in the Intermountain West have decreased in size and increased in salinity as a result of the growing demand for water from agriculture, industry and urban users as well as from climate change.”

But even among the saline lakes, the Great Salt Lake stands out. The salty elephant in the room.

A Lake Like No Other

Scientists and conservationists have long known the Great Salt Lake’s value. It is one of only a few places on Earth that can meet the food and shelter needs of millions of birds traveling along the Eastern Spur of the Pacific flyway—a migratory route spanning the Northern and Southern hemispheres. Winging their way from places as far as South America and the Arctic, up to ten million birds are drawn to the lake each year—many representing the largest gatherings of certain species in the world.

Indeed, in terms of bird stats, the lake is hard to beat. In one single spring day, more than half a million Wilson’s phalaropes—the world’s largest staging concentration—have been counted on the lake. As many as 4.7 million eared grebes, more than half of the North American population, come here every fall. And the list goes on: 240,000 red-necked phalaropes, one of North America’s largest breeding colonies of American white pelicans, 250,000 American avocets and Earth’s largest breeding population of California gulls. Those totals don’t capture the many other types of shorebirds, waterfowl and other waterbirds—including ibis, herons, ducks, cormorants and terns—that also rely on the lake each year.

Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (UDWR) avian biologist John Neill is quick to point out that behind all of the jaw-dropping numbers are hundreds of fascinating, individual stories. “The Wilson's phalaropes visit Great Salt Lake to feed,” he says. “They consume enough food to double their weight and undergo an energetically taxing feather molt, and then their fat reserves power a non-stop flight to Ecuador or Peru—a distance of over 3,400 miles!”

What’s drawing the birds here? The lake’s billions of salt-loving brine flies and brine shrimp provide a critical, nutritious food source for many birds on their migratory journey. But it’s not just the lake waters that are important—it’s the mix of lands and waters along the lake’s shore, which form the mosaic of salt content, habitats and food sources that truly make this a bird paradise. Some birds use the lake as stop-over, some as a breeding ground, and some as a safe wintering habitat. For each species, though, the lake translates to one thing: survival.

Birds Running Out of Options

A shrinking lake, then, naturally means big trouble for birds. The lake’s water drops have triggered changes throughout the lake’s intricate web of life. In a complex series of interactions that researchers are still studying, the lake’s water levels, salinity levels, nutrient levels, vegetation and inhabitant lifecycles are all interdependent. Each element, and each species of birds, engages with the lake’s resources in a unique way. Since the lake has always been naturally dynamic, the birds are used to adapting to different lake levels—but only to a point.

Brian Tavernia, Saline Lakes Ecologist with Audubon, explains: “Year-to-year fluctuations and long-term declines in lake level affect the amount, timing and location of wetland habitats for birds. It’s assumed that birds have flexibility to respond to these changes by moving to track habitat at the lake, but this tactic works only as long as some of their required habitat remains at the lake.”

Biologist Bonnie Baxter and Jaimi Butler, who run Westminster College’s Great Salt Lake Institute in Salt Lake City, are leading research on topics such as the lake’s halophiles (bacteria) and microbial diversity. The two edited a comprehensive book about the biology of the Great Salt Lake. Part of the book outlines what the downward trajectory of water levels means to various species of birds. To summarize, the lake’s lower water levels can change and eliminate feeding or nesting habitat. Receding waters can also open up land bridges, allowing predators to access bird nests that were previously protected by water. Finally, lower water levels mean higher salinity levels, dictating which creatures can tolerate different areas—and impacting the food chain. Already, the book notes, “recent bird surveys reveal a loss in numbers of critical species in the Great Salt Lake system.”

Take, for example, American white pelicans. One of the Western Hemisphere’s largest nesting colonies of these birds can be found on Gunnison Island, in the north arm of the Great Salt Lake.

Avian biologist John Neill explained it this way for Utah Public Radio: “…if it [the lake’s water] drops too low, the island becomes a peninsula and is accessible by land either by coyotes or people that might cause disturbance. Even just one coyote at the wrong time of year can cause the whole colony to abandon.”

For shorebirds, including those long-distant travelers like curlews, avocets, plovers and phalaropes, the shrinking lake is also a dire situation. That’s because few—if any—other places can provide the mix of habitat and food they need to survive their migrations. As the Great Salt Lake diminishes, so do their options.

“Even before a habitat completely disappears at Great Salt Lake,” says Tavernia, “we can expect to see potential negative effects of individuals crowding into smaller and smaller habitat remnants, such as increased disease transmission or competition for food resources.”

In 2019, a National Audubon Society assessment projected we could lose up to two-thirds of North America's bird species by the year 2100. The fate of the Great Salt Lake—one of Earth’s most vital bird habitats—could play a significant role in the realization of this grim future.

Part 2: People Need the Lake They Haven’t Always Loved

The Unfavorable Lake Effect

While there is a conservation community that has long embraced the Great Salt Lake’s worth—and birders have certainly increased in number (the Great Salt Lake Bird Festival is entering its 27th year)—the rest of the world has been a slow sell. In a desert state, where freshwater is like gold, and unique outdoor marvels abound, the salty, pungent lake remained decidedly underappreciated for many years.

“At first, my view of the Great Salt Lake didn’t differ much from that of a friend who described it as a ‘giant stinky mudhole,’” said Tim Hawkes, a former Republican state legislator and Chairman of the Board at the Great Salt Lake Brine Shrimp Cooperative from Centerville, Utah. “I had no idea of its value and figured that any water that made it into the main body of the lake was wasted because the water was so salty as to be good for nothing.”

Hawkes now serves as Chair of the Great Salt Lake Advisory Council, which was established in 2010 to help advise the State of Utah on the health and sustainability of the Great Salt Lake ecosystem. But before taking on this new role, he spent years leading efforts in the Utah State Legislature to enact policy changes to protect the lake. He knew his dismal first impression of Great Salt Lake was not uncommon. But by 2018, Hawkes had an awakening, and he embarked on a mission to share it with his fellow legislators.

The more I learned, the more I realized how much the lake is connected to our lives not just here locally, but regionally, nationally and even internationally,” Hawkes says. “I know now that it’s a vital and precious resource that we can’t afford to lose.”

Just how precious? We know the birds need the lake. But what about people? Let’s break it down.

Dangerous Dust

As a lake shrinks, more lakebed is exposed, and fine particles of dust become airborne. This is a lesson that has already been learned—the hard way. Take one example: Owens Lake, on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, which was dried out by water diversions in the 1920s. Its exposed lakebed became one of the nation’s largest sources of PM10 air pollution. Those are dust particles small enough to get into your nose, throat and lungs, and are linked to cancer, cardiac arrhythmias and heart attacks as well as asthma and bronchitis. Even if you set aside the devastating health impacts, there’s also the price tag—more than $2 billion—to try to undo the damage. As Los Angeles has had to re-water Owens Lake, residents paid for it in their water bills. For perspective: Great Salt Lake is 16 times bigger than Owens Lake.

Dr. Greg Carling, a geology professor from Brigham Young University, explains: “I think there are many reasons to keep water in the Great Salt Lake, but holding down the fine particles in the lakebed—that is reason enough. It should motivate us.” Carling is part of a team researching dust in the West. Their 2019 study showed that 90% of dust along Utah’s Wasatch Front was coming from dried-up lakebeds and desert basins.

Carling’s colleague, Dr. McKenzie Skiles, a geography professor with the University of Utah, studies another aspect of lake-borne dust. Hip deep in snowdrifts at her monitoring site in Little Cottonwood Canyon, Skiles measures aerosols in the air and snow. Her findings: dust from Great Salt Lake’s exposed bed is being deposited on the Wasatch Mountains, and it’s darkening the snow, causing it to melt faster.

“This is a story that’s not told enough,” stresses Skiles. “Human activity is directly linked to dust, and the ripple effect is huge.” Skiles’ research revealed that in just one spring storm, the amount of dust blowing off Great Salt Lake accelerated mountain snowmelt by five days. For Utah’s water managers, and for anyone financially tied to Utah’s epic powder, the timing and pace of snowmelt are critical. “The implications for our water systems are serious,” says Skiles. “Eighty percent of our water comes from snow. Our current models don’t account for the impact of dust. We are uncovering a whole different aspect to the importance of keeping water in Great Salt Lake.”

While we’re on the topic of snow and mountains, there’s one more piece to the lake story—the weather it generates itself. Every winter, when cold winds blow in just the right direction and at the right speed over the warm air rising from the lake’s salty, unfrozen waters, we see “lake effect” storms. The upshot: heavy bands of snow dump over the Wasatch Mountains—and some of Utah’s most popular ski resorts.

Dollars, Jobs and Seafood

Are you keeping up? Even if you’re not a Utahn (or a Utah skier), chances are Great Salt Lake is still a part of your life. One reason why: America’s love of seafood. When the lake’s water levels drop, salinity increases dramatically, threatening the lifecycle of a particularly unique lake inhabitant: brine shrimp, Artemia franciscana. Also known as sea monkeys, these algae-eating crustaceans are just 15mm in size, yet they are a huge component of the lake ecosystem. They are a critical food source for the birds, and they are a global commodity.

Each winter, regulated by the State of Utah, brine shrimpers haul around 9,000 tons of brine shrimp cysts out of Great Salt Lake. The cysts are dormant eggs, which are sold to hatcheries as far away as southeast Asia to provide a nutrient-rich food source for farm-raised shrimp and fish. This is the same seafood that ends up on your plate. Today, about 90% of the farmed shrimp we consume in the United States is imported, and nearly 40% of the world’s supply of brine shrimp eggs—the food that grows the shrimp you eat—comes from the Great Salt Lake.

Don Leonard, former president of the brine shrimp industry trade association in Utah, spells it out: “A healthy brine shrimp resource secures essential health for larval stage fish and shrimp—which play a necessary role in providing much-needed healthy protein for people in both developing and developed countries around the world.”

This eye-popping price tag includes not only brine shrimpers but also lake recreation and tourism, and industries built on extracting or processing minerals from the lake. North America’s only magnesium producer operates on the lake, extracting a mineral that ends up in a vast array of products from aluminum cans and computers to cell phones and cars. The lake also yields sulfate of potash, which is used to fertilize nut and fruit crops in California and Florida. The lake’s receding waters have already forced some of the mineral companies to make costly operation changes, such as extending canals and moving pumps to reach the water. “The message has always been clear and is very understandable,” says Leonard. “After being informed, most people will not accept the loss of a healthy Great Salt Lake until we have done everything in our power to preserve all that it contributes and represents.”

Part 3: Easy Choices, Difficult Changes

Dogged Conservation and Optimism

Human health. Jobs. Global industries. International wildlife significance. For Great Salt Lake, the key boxes all seem to be checked. Yet those working for the lake's protection over the years have long had to wage an uphill PR battle.

TNC made its first purchase at Great Salt Lake in 1984, protecting wetland bird habitat threatened by development. Since then, TNC has worked with a suite of partners to protect more than 12,000 acres of wetlands and uplands around the lake, including TNC’s Great Salt Lake Shorelands Preserve which stretches 11 miles and 4,531 acres along the lake’s eastern shore, and serves as a crucial buffer against fast-growing development in Davis County.

This graphic shows side-by-side satellite images from 1997 and 2022 with outlines on each image of the Shorelands Preserve, developed land, the route of the West Davis Corridor Highway, and the Great Salt Lake water level. The water level in 2022 is significantly diminished from what it was in 1997, and developed land is greatly increased.

TNC also works with the Utah State University Botanical Center to run lake-based outreach and education programs, which have reached more than 25,000 Utah students, and offers a virtual field trip that highlights Great Salt Lake for viewers worldwide. Over the years, TNC has supported new science on lake health and championed policy changes to enhance lake protection and management. In terms of conserving habitat around the lake, TNC and many other entities have made real progress—sanctuaries around the lake have also been established by Audubon, the State of Utah and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

TNC is also a leader on new projects to restore and improve Great Salt Lake wetlands and bird habitat at our preserves, which prove increasingly important to birds as the lake shrinks.

Quote: Dave Livermore

Great Salt Lake has always been one of our top priorities. For more than 40 years, many of us have been beating this drum, and trying to safeguard the most vulnerable elements of the system—and honestly, just trying to give the lake a seat at the table.

Another veteran Lake advocate, Lynn de Freitas, the Executive Director of FRIENDS of Great Salt Lake (FOGSL), is also cautiously optimistic. FOGSL is dedicated to growing an appreciation of the lake through education and advocacy programs, and De Freitas has spoken out about threats to the lake for years—from pollution to diversion to development. “It’s a never-ending battle, but I feel we’re moving in a positive direction. If we act in a timely way with a collective will, we can avert horrific results for Utah.”

Building Consensus and Change

In parched Utah, fresh water has always been top of mind for policymakers. That being said, throughout the West water is a notoriously complex—and controversial—topic. What has become increasingly clear, though, is that a “business as usual” approach to Utah’s water is no longer going to work.

According to the Utah Geological Survey website, “Increasing per capita water use coupled with rapid population growth and projected reductions in both snowpack and streamflow due to changing climate is not sustainable.” Historically, Utah ranks high on state water consumption lists. Residents themselves could choose to make easy choices that would help, from repairing leaky faucets and taking shorter showers to not overwatering their lawns. In addition, farmers and ranchers are going to be key partners in any changing water use since a large percentage of Utah’s water goes to agriculture. Legal issues governing western water users and historic laws are complicated and sensitive with far-reaching impacts. And pressures are mounting from all sides.

Perhaps because water-related policy and attitude changes are so daunting—and because of its salty character—Great Salt Lake had historically not garnered much policy attention. In fact, the state has never had a formally implemented policy to maintain lake water levels at any particular elevation range. But as the lake’s waters receded drastically in 2019, and the safety, economic and environmental costs became increasingly apparent, Utah’s leaders took note.

Tim Hawkes, the former Republican state legislator from northern Utah, had a ringside seat to the action in the capitol—and played a vital leadership role. In 2019, Hawkes led the unanimous passage of House Concurrent Resolution 10, which called on the state to support additional studies to understand the causes and impacts of the declining lake levels. A year later, the Great Salt Lake Advisory Council released a report highlighting 12 key strategies to keep water in the lake. The report’s recommendations ranged from changing Utah water law and creating new incentives for agricultural and municipal water conservation to new tools for the acquisition of water rights that could protect the lake’s inflows.

With the council’s report on the table, at the 2021 legislative session, Hawkes successfully prompted Utah policymakers to approve funding for two new Great Salt Lake projects: one to better quantify the contribution of groundwater to Great Salt Lake and its wetlands, while the other was an effort to support local governments that are interested in incorporating smart water planning into their land use planning processes.

By 2022, many more people, in Utah and beyond, were focused on the lake’s plight. And during the 2022 legislative session, a collaborative focus on conservation, water funding, water policy and water use culminated in a number of ground-breaking policy advances. Hawkes, who once again served as a Great Salt Lake champion among his fellow legislators, remembers it this way: “The 2022 session felt like a decade’s worth of water bills in a single year, including several ‘once-in-a-generation’ type bills that will shape Utah’s water law and policy for years to come.” He points out examples including:

Policy Wins

Shaping Utah’s water law and policy for years to come

2022 Session

- HB-410 – Great Salt Lake Watershed Enhancement Program (House Speaker Brad Wilson), which allocated $40 million to set up a water trust for Great Salt Lake, which is now co-managed by TNC and Audubon.

- HB-33 – Instream Flow Amendments (Rep. Joel Ferry), which significantly broadened Utah’s instream flow program and explicitly authorizes transactions to benefit Great Salt Lake. This bill marked a historic change for Utah water law, altering the long-standing and wasteful “use it or lose it” stipulation for water rights holders.

- HB-429 – Great Salt Lake Basin Integrated Plan (Rep. Kelly Miles) appropriated $5 million to the Utah Division of Water Resources to study and gather data about the five watersheds that feed Great Salt Lake, ensuring we have a better understanding of the complex water supply and demand in the Great Salt Lake Basin.

- HB-242 – Secondary Metering Amendments (Rep. Val Peterson) invested $250 million which, when paired with private matches, aimed to fix the longstanding problem of unmetered outdoor watering and encourage water conservation in municipal users.

- Several other bills that funded critical research and helped shore up long-term funding for the Lake and its water supply.

After the ground-breaking session closed, Hawkes noted “Utahns can and should be proud of the unprecedented steps Utah is taking to protect this vital resource.” Momentum for policy reform around water and Great Salt Lake continued in Utah’s 2023 and 2024 Legislative sessions, with more key advances including:

2023 Session

- HB-491 – Amendments Related to the Great Salt Lake (Rep. Mike Schulz), established the Office of the Great Salt Lake Commissioner. The Commissioner is appointed by Utah’s governor and is tasked with preparing and implementing a long-term strategic plan for getting the Lake to a healthy water level and ensuring coordination among all of the state agencies working on GSL issues.

- HB-513 – Great Salt Lake Amendments (Rep. Casey Snider), increases royalties on new mineral extraction on the Lake, and requires mineral extraction operators to use technologies that minimize water depletion.

- HB-349 – Water Reuse Project Amendments (Rep. Casey Snider), which prohibits wastewater reuse projects within the Great Salt Lake Basin that would cause water to stop flowing into the Lake.

2024 Session

- HB-453 – Great Salt Lake Revisions (Rep. Casey Snider), which places constraints on the mining industry’s use of Lake water and protects water dedicated to Great Salt Lake from extraction. The bill also applies a tiered tax for mineral extraction based on Lake levels and consumptive water use, and it tasks the state engineer with regulating the measurement and distribution of Great Salt Lake water rights, setting limits on the amount of water that mineral extraction companies can take or divert from the Lake during low water years.

- SB-18 – Water Modifications (Rep. Scott Sandall), allows for the creation of “saved water” in agricultural water rights, which makes it easier for water-rights holders to send portions of their water rights to flow downstream to reach Great Salt Lake.

Taken together, these bills represent a major sea change for Utah water policy—one that required unprecedented collaboration. Dedicated lake advocates like TNC joined forces with key legislators to enact these landmark water and Great Salt Lake policies. For Megan Nelson, TNC Utah’s Director of Policy and External Affairs, the recent progress has been a highlight of her career. “TNC has been working for a long time on many of these policy changes that benefit the lake, agricultural producers and communities across Utah,” says Nelson. “It’s been incredibly rewarding to see the broad stakeholder and legislator support that enabled the crucial legislative wins of the last six years. Utah’s water law has really risen to meet the challenge facing Great Salt Lake.”

Where We Stand Now

The lake’s growing public following and Utah’s recent water policy headway has set the stage for where we are today. For the first time in history, our state is pursuing a coordinated and strategic intervention for Great Salt Lake.

Below are some of the current programs and advances TNC is most excited about:

The Great Salt Lake Watershed Enhancement Trust

TNC and National Audubon Society are co-managing the Great Salt Lake Watershed Enhancement Trust, a ground-breaking public-private partnership established in 2022 with an initial $40 million grant from the state. The trust is designed to advance projects and voluntary transactions to retain or enhance water flows to the lake and improve or preserve wetlands. Already, the trust has facilitated water transactions totaling 68,000 acre-feet of water for the lake. The trust has also supported projects to restore 19,000 acres of lake wetlands through the end of 2024. Learn more about the Great Salt Lake Watershed Enhancement Trust.

Office of the Great Salt Lake Commissioner

In 2023, the Utah Legislature created the Office of the Great Salt Lake Commissioner. The commissioner has been tasked with developing and maintaining a strategic plan as well as coordinating collaborative work among all agencies and interests in relation to the lake. TNC and the trust are working closely with the commissioner and other state entities to ensure our efforts are integrated toward the common goal of a healthy lake level.

A New, United Front

Never before have so many different people, entities and organizations been focused on solutions for Great Salt Lake. As Utahns recognize the lake’s value and face the reality of growing water demands and increasing climate change impacts, all of us are re-thinking how we use our water. Individuals, agricultural producers, Tribes, industries, communities and cities, environmental and wildlife groups, scientists, civic leaders and state agencies are coming to the table with fresh energy and ideas. Only by working together will we find collaborative, voluntary solutions that deliver a healthy future for Great Salt Lake—and for all of us.

Alongside this exciting momentum comes a new kind of pressure: to avoid slipping back into complacency. While the lake levels have rebounded to some degree and unprecedented collaboration is underway, Great Salt Lake remains at risk. The growth projections, water demands and climate change predictions for our state are clearer than ever. Rather than being out of the woods with respect to the lake, we are truly just beginning to see the extent of the “forest” around us. Since there is no silver bullet, stamina and patience will be key to navigating the long and complicated journey ahead to sustain the lake. TNC Utah’s new state director, Elizabeth Kitchens, explains, “We need every tool in the toolbox, and some new ones. Great Salt Lake is an immense watershed with many complicated and interconnected elements that touch many lives, livelihoods and industries. The most important thing is that we all work together.”

Seeing Beyond Today

While Tim Hawkes always knew that the lake’s importance to public health and the economy would motivate the public and legislators, he, like many of us, is also moved by the plight of the birds. “I remember one moment it hit home for me, the amount of life the lake supports,” he says. “I took a trip to Promontory Point along the Union Pacific causeway in early autumn. From the moment we could see water south of the causeway to the moment we arrived on Promontory, the edge of the water was black with a thick band of countless birds. It went on for mile after mile. I've never seen so many at one time and in one place.”

It’s the type of epiphany that’s welcomed by Ella Sorensen, manager of the Edward L. and Charles L. Gillmor Audubon Sanctuary, a 3,597-acre preserve on the lake’s south shore. A chemist by training, Sorensen has spent decades studying the Great Salt Lake’s birds and writing about the lake for the Salt Lake Tribune. When I ask her how to explain the lake’s importance to someone on the street, she sighs. “It’s not effective to say things about Great Salt Lake. What works is to bring people out here.”

As Sorensen flicks mud from her boot tip, her soft, white hair lifts in the afternoon breeze. She often spends hours walking her daily route through the sanctuary’s sludgy marsh, which provides vital habitat for migratory shorebirds such as American avocets and snowy plovers.

Quote: Ella Sorensen

I bring people out here who’ve lived in Utah their whole lives, but never understood the lake until they came and saw the birds and the wetlands for themselves. It’s tremendously powerful.

Perhaps that sheer lake life force is part of what acclaimed author and environmental advocate Terry Tempest Williams wanted us to contemplate 35 years ago, when she published her famous book Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place. One of the lake’s most celebrated and eloquent defenders, Williams used her memoir to show how her own life was inextricably linked to Great Salt Lake and the birds. In truth, so is ours. We all share in nature’s bounty, and in its decline.

In 1990, Williams described living in a “virtually uninhabited” area near the Great Salt Lake. Today roughly 80% of Utah’s population (more than 3 million people) live within 20 miles of the lake. What will the next 30 years bring? For people? For the Great Salt Lake? For the birds? That answer, according to Williams, hinges on our choices. “The eyes of the future are looking back at us,” she wrote in Refuge, “and they are praying for us to see beyond our own time.”

Continue learning

Conservation Legacy at Great Salt Lake

Since 1984, TNC has been a driving force advancing science, habitat protection and education to benefit Great Salt Lake. Discover TNC’s role as a conservation leader and our three areas of focus to safeguard vital wetlands.