Creating Resilient Forests

Michigan’s forests provide so many benefits to nature and people—and they have even more to give.

Just over half of Michigan is forested. These 20 million acres represent a vital part of Michigan’s nature, providing a home to iconic wildlife like the gray wolf, black bear and migratory songbirds that fill the trees with color in the spring. Michigan’s forests are also an important legacy for people. They support over 100,000 jobs and a $20 billion economy. And, they are core to our recreational heritage—many Michiganders have fond early memories of walks in the woods.

Our forests provide so many benefits to nature and people—and they have even more to give. In a changing climate, forests represent a powerful carbon “sink” that can offset greenhouse gas emissions. Healthy forests store more carbon, but the health of Michigan’s forests has been challenged by a complex history of ownership and intensive use, as well as encroaching pests and disease.

TNC is demonstrating sustainable, data-driven forest management practices—and encouraging others to use them as well—to ensure Michigan’s forests remain healthy, resilient and productive for generations to come.

By the Numbers

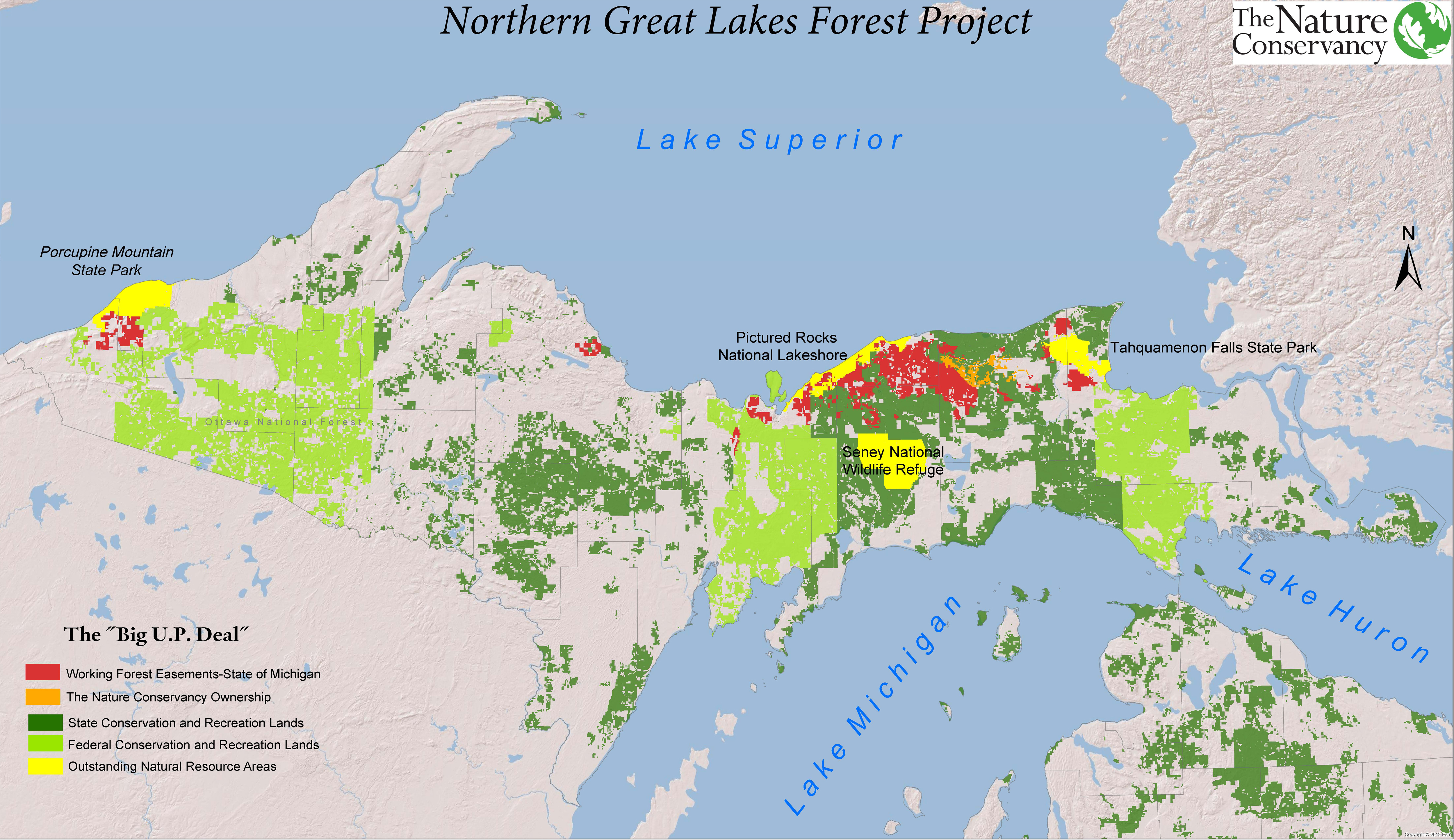

- 271,338 acres protected in total, across eight counties.

- TNC’s 23,338-acre Two Hearted River Forest Reserve established.

- 248,000 acres of working forest easements held by the state.

- More than 52,000 acres of wetlands protected.

Protection

In 2005, TNC and the State of Michigan—with the support of the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund, the Federal Forest Legacy Program and many generous donors and partners—protected over 270,000 acres of some of the most spectacular forests, lakes, rivers and headwaters in Michigan. This vast public-private partnership, dubbed the “Big U.P. Deal,” is a conservation project that keeps on giving—providing a strong foundation for learning, inspiration and impact as TNC moves forward into an exciting new chapter for resilient forests in Michigan.

Demonstration

The Big U.P. Deal led to the creation of the Two Hearted River Forest Reserve, TNC’s first reserve in Michigan, which acts as a “living laboratory” where we can study the practices that make forests healthier, while also supporting sustainable forestry jobs and promoting climate benefits.

Using sustainable logging practices, we can improve the health and diversity of the forests. We promote sustainable forestry practices, such as selective logging, which involves assessing each individual tree to decide which trees should be cut for the health and diversity of the whole forest.

Partnerships

TNC works with state and federal agencies, Indigenous communities and private landowners to scale up the conservation of healthy Michigan forests. We share our results and knowledge widely to elevate awareness of the economic, ecological and climate mitigation potential of sustainable forestry practices; to promote Forest Stewardship Council® FSC®-C008922 certification for managed forestlands; and to encourage investment in a more sustainable forest products industry.

In October 2018, we worked with the U.S. Forest Service–Ottawa National Forest to complete a wetland restoration project that involved building 480 feet of boardwalk. Deep within the Michigamme Highlands of the Upper Peninsula in the McCormick Wilderness Area—we worked with two strings of specially-trained pack mules to construct a boardwalk over a mile into the wilderness. This project was funded through a restoration timber sale conducted on forest service lands.

Science

Science is the foundation of all our work, from climate science research projects to quantitative metrics for forest health and climate sensitivity. We map priorities and other research, including TNC’s national resilient and connected network study, to prioritize forest protection projects.

Keep Learning

Explore these resources to learn more about our work in Michigan's vast forests.

-

Resilient Forests Overview

Four-page overview of the strategies employed to protect Michigan's forests. Download

-

Michigan's Forest Biomaterials

The Michigan Forest Biomaterials Institute partnered with TNC to create and release this webpage, designed to showcase the state’s potential to create a strong bioeconomy. View the Story Map

-

Working Woodlands

TNC’s Working Woodlands initiative assists private landowners (of properties greater than -2000 acres) with forest management planning, becoming Forest Stewardship Council® FSC®-C008922 certification and enrolling in carbon markets. Learn More

-

Family Forest Carbon Program

The Family Forest Carbon Program is an option for owners of smaller properties, helping them improve management practices and grouping properties to qualify them for carbon incentives. Learn More