Delaware's Stream Stewards Program

Discover how you can become a Stream Steward and help protect Wilmington’s drinking water supply.

About the Stream Stewards Program

Stream Stewards is a successful watershed stewardship program that provides a model for accomplishing the goals of community science, youth engagement and public education by providing opportunities for people to learn about and engage with their local waterways.

The partnership between The Nature Conservancy, First State National Historical Park (FRST) and Stroud Water Research Center provided the foundation for the growth and development of Stream Stewards into a sustainable program with a largely self-sufficient team of dedicated volunteers who conduct water quality monitoring, assist with public education at events in the park, and act as advocates for clean water in their communities.

The streams in First State National Historical Park that feed Brandywine Creek provide an ideal learning environment for volunteers of all ages to gain an understanding of stream ecology and the importance of watershed protection. By engaging in water quality data collection, Stream Stewards contribute to science-based management actions that will have a real conservation impact in the park.

One of the main goals of the Stream Stewards program was to create a place-based program in FRST’s Brandywine Valley unit to build awareness and visitor engagement in the relatively new national park. Since the program’s inception in 2016, FRST has continued to add staff and programming at the Brandywine Valley unit and now has the capacity to administer a full range of volunteer roles, manage natural resources, and provide educational and youth programs. In addition, the park is now supported by Friends of First State, a Friends Group that helps to provide the park with funding and resources. FRST is now well-positioned to take on full oversight of the Stream Stewards program and ensure its sustainability into the future.

Stream Stewards Video Series

Stream Stewards is a community science program designed to engage people of all ages and backgrounds in watershed stewardship. We’ve created a four-part video series consisting of a program overview and a look at the three main components of Stream Stewards: youth engagement, community science, and public outreach and education.

Stream Stewards Video Series

Program Requirements

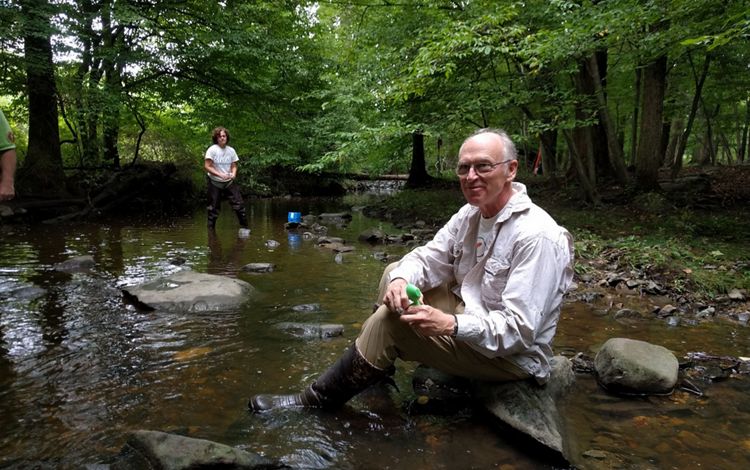

Two Stream Stewards community scientists, visit their stream monitoring location in First State National Historical Park.

You must be at least 18 years old to apply to be a Stream Steward and be willing to participate in at least four half-day training sessions that will take place in First State National Historical Park.

After completing the training, Stream Stewards must complete at least 20 hours of service, which can include collecting water quality data at monitoring sites, participating in stewardship projects such as plantings and invasive species removal and assisting with our bi-annual watershed clean-up events or other outreach and education opportunities.

Stream Stewards will:

- Learn about watershed ecology

- Be trained in water quality monitoring and data collection techniques

- Connect with nature in First State National Historical Park

- Contribute to conservation and natural resource management

- Become Community Scientists

- Join a diverse community of volunteers and stewardship leaders

Become a Stream Steward

To learn more about the program please visit the First State National Historical Park (FRST) or contact the park directly at firststate@nps.gov.

Reflections from Stream Stewards Project Manager Kim Hachadoorian

When the Rain Comes

When the rain comes, it reaches the earth and travels the path of least resistance, drawn by gravity and a seeming wanderlust. In forests and meadows, the rain’s journey will be meandering and leisurely. It will drip off leaves and soak into soil. Some of this water will be absorbed by thirsty plant roots, and some will continue to wend through underground channels, eventually flowing into a stream or river. By contrast, in cities and suburbs, the rain’s progress is usually direct and hasty as it rolls off rooftops and runs down roadways into storm drains and a system of underground pipes. During a heavy rainfall these pipes can send a deluge into waterways, causing them to overflow. That’s when serious flooding can occur. But we can alleviate this problem by using nature to slow the rainwater and allow it to spread out.

Rocky Run is a multifaceted little stream in Wilmington, Delaware that demonstrates both these rainwater trajectories. One section of Rocky Run flows through the serene woods of First State National Historical Park into Brandywine Creek, which eventually joins the Delaware River. But before all of that happens, the water in Rocky Run must travel through a concrete channel, along a busy roadway crowded with shopping malls and parking lots. Rainwater flows rapidly over these paved surfaces, downhill and into the stream.

If you are in the park when the rain comes, standing on the bank of Rocky Run among the towering tulip trees, you will see the water level rise quickly, completely submerging the large rocks you stepped upon to cross the stream. The surface of the water may have an oily sheen or a film of soapy looking bubbles. And you will likely see a regatta of trash, washed off the paved surfaces and carried into the stream by the rain.

Then, like water draining from a bathtub, the level recedes as quickly as it rose. This happens because the land in the park gives the water somewhere to go. No longer constrained by a concrete channel, the stream can spread out over the banks like a blanket. Then it seeps into the soil, finding passage through connected vertical air spaces that create finger-like tunnels for the rainwater to travel down. The soil is a sponge that stores and cleans the water, and then releases it slowly back into the stream.

If we add more of these natural sponges to our urban areas by increasing green spaces, we can lessen flooding and create a filtration system that delivers cleaner water to the rivers that provide drinking water for many of us. Every park, every garden, every green space, no matter how small, can help with this effort. Nature gives rainwater the time and space to slow down and spread out. We can’t stop the rain, but we can change our cities so that when the rain comes, it has somewhere to go.

Think Global, Act Local

Get global conservation news & the latest on local opportunities & projects.