Nature for Cities and Communities

From urban centers to wild spaces, protecting nature improves quality of life.

By 2050 there will be nearly 10 billion people on Earth. Two-thirds will live in cities.

Quote: Laura Crane

Our science shows that when cities and communities protect and enhance nature, the built environment can become more livable, sustainable and equitable.

Wherever humans live, we depend on nature for our food, clean water, clean air and for our physical and mental health. With smart planning, science-based solutions and strong partnerships, TNC is working toward the green cities of tomorrow right here in California. We’re helping people and nature adapt to a changing climate and prepare for the impacts to come.

Innovating in California: California is the most populous and most ecologically diverse state in the US. We also boast the fifth largest economy in the world, with a long history of social and environmental innovation. Our state can serve as a testing ground for conservation in the face of intense development and resource pressure from continued population and economic growth.

At TNC, our work is facilitating California’s ambitious transition to a zero-carbon economy while ensuring that clean infrastructure doesn’t put nature at risk. As California grows and adapts to climate change, our state can show the way for global cities and communities to protect nature while improving safety, sustainability, livability and desirability.

Nature and Communities

The way cities and communities grow has an enormous impact on people and nature. From avoiding heat islands to providing migration corridors for species in need, there are abundant opportunities to improve the urban landscape for people and nature. At TNC we approach this work using two strategies: ensuring cities grow with nature in mind, and intentionally transforming the existing urban footprint to bring nature back into cities and communities.

Through innovative conservation efforts, we can protect against the worst impacts of climate change and help California’s cities and ecosystems adapt to a changing world.

Connecting Habitat

As climate change forces species to migrate farther than ever, we’re working to remove some of the barriers that prevent them from making the journey.

We’ve worked with our partners and used our science to identify Southern California’s top 15 habitat connections or “linkages.” Restoring these connections would have an outsized impact on species’ ability to move safely throughout the region. One of these habitat connections is the Santa Ana to Palomar linkage, currently severed by the I-15 Freeway in Temecula.

Destination Nature: A Path for Mountain Lions

Click the green arrow below to hear episode two of Destination Nature.

Stacy Raine [SR]: Late one night, a lone mountain lion walks silently toward a concrete bridge and eyes the creek path underneath. He’s known to the researchers that collared and track him as M93. He’s a young lion – just two years old. Until recently he’d been with his mom, learning how to survive. Now, it’s time to establish his territory somewhere else.

In the last six weeks he’s covered the roughly 60 miles from the top of the Santa Ana mountains in Southern California down to the bottom. He’s ventured farther south, into the mountains of Camp Pendleton, the expansive military base just below. Then he kept moving, making his way over to the rapidly developing outskirts of Temecula, one of southern California’s fastest growing cities.

He wants to go under that bridge, to follow Temecula creek, the natural migration path for animals in this area. He wants to get to the other side, where he can more easily find territory and suitable mates.

But there’s one big 8-laned problem holding him back.

This is Destination Nature, a podcast by The Nature Conservancy that takes you into the field to

hear the stories behind conservation projects from all around the globe.

I'm Stacy Raine.

Interstate 15 begins in San Diego, and if you drive about an hour north along this road, you'll find yourself in the city of Temecula. On this stretch of the 15, you’ll probably notice how many rocks dot the green vegetation of the Santa Ana mountains off to the west. Some jut out so far, they look like they might come tumbling down at any moment. Off to the east, past the golf course, you can see the looming peeks of the Palomar Mountain range.

What you probably won’t notice as you drive on this busy highway is that Interstate 15 cuts right through the only natural migration corridor for mountain lions in this area.

This is a big problem for M93. This highway roars with traffic. It’s no place for this lion, and he knows it.

Winston Vickers [WV] We've had mountain lions that had radio collars, so we knew exactly where they walk, uh, come down, there's creek for instance, and come within about 60 yards of the bridge and then turn around.

SR: Dr. Winston Vickers is a research veterinarian with the Wildlife Health Center at UC Davis. He and Trish Smith, an Ecologist for The Nature Conservancy, have been working together for many years to study mountain lions in this area to understand the threats they are facing.

Tracking collars make the job a little easier. There’s really only one way to put a collar on a mountain lion. You have to capture him, help him go to sleep, put your hands uncomfortably close to his face, and secure the collar around his neck as carefully as you can. Common practice for Winston. He places roadkill deer in places that, thanks to trail cams, they know mountain lions frequent, and when a lion enters the trap:

WV: We would go immediately to that location and sedate them, uh, with anesthetics and put collars on them, sample their blood, sample, their tissue, their hair, their whiskers, all kinds of samples to learn as much as we could from each handling event with the mountain lions.

SR: It’s exhilarating and rewarding work, but it can also be a little unpredictable.

WV: I have had one just to suddenly stand up with us right beside it on our knees. And then he was eye level with us. But, uh, of course what he wanted to do was leave. And so, we just, I just sort of grabbed his, he had his radio collar on, so I just kind of grabbed him and directed him away from us and he left cause that's what he wanted to do. Um, you know, when they wake up, suddenly they're very confused and you know, they're groggy. So, it's not like there's a great deal of danger there, but, but it can be disconcerting.

SR: Disconcerting at times, but worth it because they’ve learned quite a bit from tracking these lions.

WV: They're migrating animals that are looking for homes and they're very compelled to explore and keep going. Their ranges are large. An average home range of a male is around 150 square miles in this area and females about half of that. And if you think about 150 square miles in an area like this, you cannot cover that much ground without crossing a highway or two or three. So just to maintain a territory, they have to be crossing highways and that's why a highway like I 15 tends to divide territories

SR: M93 has reached this juncture that leads under the interstate for a reason. It’s the path that will take him from the Santa Ana mountains to the Palomar Mountain Range. He needs to pass through – he’s driven by instinct to migrate, maybe away from other males, maybe due to hunger, and so far, he hasn’t been successful finding a place of his own.

M93 is pinched, as these scientists say, into this part of the mountains due in large part to development, and specifically to the interstate that cuts through the normal migration corridor for mountain lions and other species as well.

What was once one large population of mountain lions spanning across California has now been divided into ten, all becoming genetically different from each other. Six of those subpopulations are in the coastal California area south of San Francisco and all of them are experiencing a loss in genetic diversity to some degree.

WV: This population is the most inbred population anywhere on the globe, actually, of mountain lions except uh, the Florida panthers and they are an endangered subgroup of mountain lions, in the Everglades. And the Florida panthers went into this extinction spiral as they say, or extinction vortex is a term that used. And so, what we're trying to avoid is the same thing happening here and the population beginning to decline dramatically.

And other than them, this is the most endangered population from the standpoint of, of the effects of inbreeding.

SR: In cases like this, where a population is cut off from opportunities to mate with other populations, they experience what’s called “inbreeding depression.”

WV: This is a term that's applied when kittens don't have as good a survival rate. There are sperm abnormalities in the males. The females may have less fertility, so you have a net effect of fewer kittens per female per year. Uh, and so over time, naturally a population declines if there's no new animals coming in to replace that, that lack of reproduction.

This sub-population of lions in the Santa Anas, this one group that used to be part of a whole population that mixed genes across California, is suffering from reproductive losses so great that they can’t sustain their population over time.

SR: At the bridge along Temecula Creek, M93 hears the traffic, he sees the cars, the lights. He weighs his options.

WV: They tend to approach highways like this one and then turn around. In many cases they rarely try to cross even when structures are present, where they could safely cross. If the highway is super busy.

SR: M93 senses that crossing could be deadly, but the decision not to cross is just as deadly for these animals. Not crossing means the entire population here in the Santa Ana mountains could go extinct by 2050.

It’s very rare to see a mountain lion in the wild, but it does happen on occasion. Trish, TNC’s Ecologist on this project, said she’s spent a lot of time in the field and:

Trish Smith [TS]: In my 30 years of being a biologist. I've seen a mountain lion; I think 11 times in the wild.

They're very elusive. I sensed their presence before I actually saw them. Most times they're either behind a rock or up in the brush or I just kind of look to the side and there they were. And then they take off like lightning. They're just gone. As soon as you see them, they leave. You don't even hear them. Um, even when they're running away.

SR: It’s surprising they are so quiet considering their impressive size. As adults, these felines are usually 6 to 8 feet long from their nose to the tip of their tail. Females can weigh around 85 pounds and males are even larger at 150 pounds.

WV: They're front paws are a little bigger and a big male will have a paw, if his claws are extended, the size of a man's hand. So very, very big powerful instruments.

They have powerful, slightly longer rear legs so that they're good at ambushing and jumping. They can jump long distances and, and jump 12 feet in the air, uh, to clear fence

SR: These majestic animals are known by more than 80 different names – so many, in fact, that one of its nicknames is “cat of many names”:

WV: Cougar, Puma, Catamount and panther in the case of Florida, but in South America, central and South America, they have a number of other Spanish-derived names.

SR: They’re also known as ghost cats and mountain screamers, and if you’ve ever heard the blood-curdling vocalization of a female mountain lion, you know why those names are so fitting.

WV: They don't roar. Uh, they don't have that capacity.

They, uh, do something of a scream, uh, at times that people have likened to a, a woman's screaming. That's primarily, uh, females in heat. When their advertising their status, they purr, usually females interacting with the kittens they chirp the females, uh, and the young oftentimes chirping each other like birds and they sound like birds.

They growl.

SR: But as M93 walks towards the Temecula Creek Bridge he probably isn’t making any noise at all. He is looking, listening, smelling, wondering if he should try and cross. He doesn’t.

The thing is, the path along Temecula Creek that leads under that interstate is actually a safe place for him to move through. The bridge is located right next to protected lands in the Santa Margarita Ecological Reserve managed by San Diego State University. The other side is protected by Riverside county. He could make it through and work his way to the Palomar mountains. He just doesn’t know it.

Cara Lacey [CL]: It's a functional wildlife crossing, but it's not functioning to the point where it should be.

SR: That’s Cara Lacey, an urban planner for TNC. She thinks about how we can better plan our use of land in a way that helps protect wildlife, and one place she thinks a lot about is this bridge.

She says there are so many deterrents that mountain lions and other species aren’t using it like they could be.

There is, of course, the problem of seeing moving vehicles. The cars zooming above, the headlights streaking past. There are also overgrown, invasive plants blocking M93s line of sight. He can’t see to the other side, and studies show that without knowing they can safely cross, mountain lions usually won’t even try. And, a lot of times, people are there, partying, camping, drawing graffiti under the bridge.

If that isn't enough to deter this lion, the traffic sounds that are magnified by the bridge structure itself probably do the trick.

CL: That's just constant. It's sharp noises. It's rumbling noises.

WV: So, there are things about the environment that they tend to, to have almost like an invisible barrier.

SR: So, mountain lions end up trying to cross the interstate in places nearby, and it’s not going well for them. There are not very many mountain lions here as it is. Winston estimated that there’s maybe 5 or 6 males and 11 or 12 females in the Santa Ana Mountains. Less than 20 adults, then add in a few kittens and some adolescents as well. If we’re lucky – 30 in all. Not very many, and Certainly not a large enough gene pool to keep this population healthy. They need to make connections with other groups of mountain lions.

So, these big cats are motivated to find somewhere else to roam and find mates. If the bridge doesn’t seem like a safe place, and if they are very bold, they chance Interstate 15. And a very few times, they’ve made it across.

WV: Of the animals that we have identified that did come into the mountain range, which is only three over the time of the study, um, only one survived and reproduced that we detected. Young mountain lions don't live very well anyway. They have to compete with adults. They have to cross strange territory that they don't know. Uh, they have to cross roads that they're not familiar with, so they don't know where the safe points are. So, they have a lot of barriers just getting around the landscape as new individuals, like going into a new neighborhood and they're trying to find their way around where they can run into hazards.

SR: Three made it over to the Palomar mountains, one survived. That was over the course of the study he is referring to, the Southern California Mountain Lion study. It’s been going on for nearly 18 years.

The situation is dire. They could go extinct in as little as 12 years.

But why does this matter? What’s the big deal with these big cats?

WV: All the large predators have major ecological roles of regulating ecosystems. The mountain lions help regulate the coyotes and the smaller carnivores. And if they're not there, they tend to - those animals tend to increase in numbers and that can have an impact, a negative impact on ground nesting birds and, and other wildlife. And then if they're not regulating the deer, the deer can have an over abundant impact on the vegetation. And that can change the ecosystem in a broad way. And that's been documented in multiple ecosystems with multiple large top predators that when the top predators are removed, then those animals below them on the food chain tend to increase in number and it alters the entire ecosystem.

SR: What we see happening to the largest predators in an environment means that the smaller ones are suffering too. It’s not just the mountain lions that are getting pinched into this area and can’t cross the road.

CL: The mountain lion is a really great indicator of the issues that most species are, are experiencing right now with additional roadways, additional, um, highways and freeways as well as additional housing encroaching into their environment.

SR: Of course, there’s also protecting nature for nature’s sake. But even more surprisingly, they play an important role for people:

WV: It’s even been shown that with mountain lions and deer, if deer numbers increase, then, uh, collisions with cars increase.

SR: And they keep a check on some of the species we also don’t want too close, especially in our homes, like rats, for one.

TS: With these Mezze predators like raccoons, skunks, possums, they aren't particularly popular in our neighborhoods. And when their populations get out of whack because there's no longer larger predators like coyotes, you'll really see even more cascading effects in terms of an outburst of rats, which then become a problem in people's yards and in people's homes. So, by keeping the balance of predators, whether it's mountain lions, coyotes, and the smaller predators, we can really keep a healthy ecological system, not only for nature but for people as well.

SR: Inbreeding due to severed migration corridors isn’t the only threat to these lions. Mountain lion territory is shrinking under pressures from development, bringing us closer and closer to the places they frequent, and forcing them to come closer and closer to us in search of food or territory.

CL: We're seeing both the barriers of highways, but also the increased urbanization that's impacting their, their movement and, and how they're, they're able to live and survive.

SR: And particularly, there’s a problem with the way we’ve developed. We’ve fragmented the landscape. We’ve put a subdivision over here, a shopping center over there. As Winston put it, we’ve essentially just created “more edges,” making it much harder for mountain lions to avoid their biggest predator – Us.

When a mountain lion snatches a pet, which happens occasionally, or kills someone’s livestock – which happens more frequently, the owner can seek a permit to kill the lion. People want to protect their animals, the mountain lions want to get their next meal, and the resulting conflict is bad for the people and their animals and can be deadly for the lions.

WV: The more narrow you put the spaces between the, the areas of urbanization, the more likely they are to move into urban area as they're trying to find their way through.

SR: M93’s story is not a happy ending. The night he turned away from the bridge was in 2012, and he never did cross to the other side, though he went back to the interstate several times. Two years later, he was poisoned.

His family’s story isn’t much better. His mom, F89, was killed by a male lion, perhaps while protecting her offspring. His brother, M91, was killed on a toll road during their journey together early on. His half-brother, M118, the one F89 might have died trying to protect, was legally killed for threatening livestock.

Before M93 died, though, he’d established a territory and fathered at least two kittens. One of his descendants, M122, was later killed after also taking someone’s livestock. We don’t know what became of the other one.

TNC is working hard to save these lions, bringing together partners to find ways to help them migrate safely both in the short-term and in the long-term.

Ideally, we’d create a “system of crossings” as these scientists put it, giving species several safe routes to pass over or under the interstate. Different species want to migrate in different ways. Trish puts it pretty simply:

TS: You won't catch a butterfly going through a culvert or an underpass of a freeway. An overpass would probably work better also for our lizards as well.

To determine exactly the best way to create safe passages for wildlife in the Santa Ana Mountains, TNC and our partners consulted with wildlife crossing experts. We also brought in the state's highway agency, Caltrans, that owns and manages the highways and would undertake the building of any structure. Then UC Davis, funded through a grant from the State of California, brought in civil engineering students from California Polytechnic University Pomona to illustrate what these crossings could look like.

CL: Cal Poly looked at three different conceptual designs and feasibility studies and the three designs were one to upgrade the Temecula Creek Bridge. The other was to look at a culvert that could be, um, kind of bored underneath the freeway under I 15 to reconnect the habitat there. And they also designed an overpass and it would span over the entire freeway, um, with a central support.

SR: Cara and Trish are particularly excited about this overpass, which could be as wide as a football field. There’s one big difference between regular bridges made for people and this design made for wildlife:

TS: It would be vegetated. So, you would have soil actually on top of the bridge. It wouldn't be a roadway bridge that used is used by cars. It would be solely for wildlife use and so we would place a layer of soil on top, they say like three meters of soil on top of which you would plant native chaparral habitat or coastal sage scrub habitat, the habitat that's found on either side of the roadway so that wildlife that are approaching the bridge, just see it as another patch of habitat they're moving through.

SR: It would stretch right over those 8-lanes of interstate, starting on SDSU’s Santa Margarita Ecological Reserve – but there also needs to be a protected space on the other side that’s safe for mountain lions.

This is where a recent TNC land purchase comes into play. You can build 5, 10, 15 crossings, but if the land around the crossing isn’t protected, they will be obsolete as soon as development takes up the open space. TNC was keenly aware of this and found the perfect spot to purchase and set the stage for future wildlife crossings - right across the interstate from the Ecological Reserve

TS: Rainbow Canyon property is just 73 acres, but it's pretty representative of the Santa Anna Mountains in this particular region.

SR: By that she means that it stays green and has dense, shorter vegetation. It’s very rocky, has a few rare plant species including Rainbow Manzanita, and wildlife like birds, foxes, bobcats, and of course, mountain lions.

But getting the permits in place and constructing these two new passageways – the culvert and the overpass – will take decades, and that’s after the funding is in place to do it. But time is something these mountain lions don’t have.

TS: Temecula creek is the only natural corridor that we have now that's linking the Santa Anna mountains eastward to the eastern peninsula ranges. And so, because it's the only viable crossing we have, we need to figure out how to fix it. And that's where ideas of enhancing the habitat, dealing with the roadway noise by putting in sound buffers underside, the a bridge overpass might be measures that will enhance its function for not just mountain lion spot, all sorts of wildlife species.

SR: The current deterrents there – vegetation overgrowth, lighting, noise, even people - these things are relatively easy fixes, ones that might take only two or three years.

We need to fix that bridge, and make sure the animals still aren’t trying to cross elsewhere.

WV: We would like to prevent them from even trying it with fencing. The hope is that they will move alongside the fence to the good crossing and cross there. Just having a crossing doesn't do it.

SR: Longer term, the culvert and the overpass structures can be built to give mountain lions and other species safe places to cross that work for them. Some species want to stay in open air, some are happy to go underneath. There’s a real need for both, in addition to the upgraded bridge path.

CL: Of course, in an ideal world, we could have all three. Um, and we'd fund all three and we'd have the ability to build all three,

SR: These crossings, once completed, and the land protection around them, will reconnect habitat and species here. The hope is that this serves as a model, encouraging new crossings and habitat protection elsewhere in the state and even further afield. That eventually all these populations will no longer be cut off from each other – they’ll have clear migration routes that keep them healthy and encourage them to move in places not so close to human habitat.

If this work can be done – if crossings are built and the right land is protected, the future is bright for wildlife here. They can finally – easily, safely – cross that interstate.

CL: There's no more deaths, there's no more impacts to animals. They have the ability to finally cross and to find each other. Um, in terms of the mountain lion. And so, you'll start to see more genetic diversity, which is really what we need to have for the mountain lion. But that's also an indication of what can happen for other species.

So ideally, we would want to see generation after generation start teaching their young how to use these crossings instead of trying to cross the freeway. Of course, we'll have wildlife fencing, but they'll know how to follow that and get to the crossings that they need to use. Once you get, a species starting to cross they have the ability to teach their young how to use it. And seeing that happen is really, really impressive.

SR: It’s possible that, one day, maybe a descendant of M93’s kitten, the one that we hope is still somewhere out in the Santa Ana mountains, will be led across this overpass by his mother, led through this new landscape over the roaring interstate, this place just for them that will lead them safely to the other side.

Thanks to Winston Vickers, Trish Smith, and Cara Lacey for being on this show.

Destination Nature was produced by Katie Bacon, Amy Hepler Welch, and me, Stacy Raine with help from Kristin Mullen. Special thanks to AudioRaiders for the production sound, Bradley Morgan Dale for the music, UC Davis for some of the sounds, and the Dallas Audio Post for their editing work on this show. But most importantly, we are so grateful to our supporters who made this work, and this story about the work, possible.

Next time on Destination Nature, take a trip to Philadelphia to see how nature is helping this historic city fight water pollution.

In 2018, TNC acquired a 73-acre property adjacent to I-15 and directly across from the Santa Margarita Ecological Reserve. Our goal is to design wildlife crossings that go both over and under the freeway to help multiple species, including a local population of mountain lions that has become isolated in the Santa Ana Mountains. Inbreeding and lack of prey could drive this population extinct in the next 20 years, so we’re linking two protected areas and establishing a path that these animals desperately need. Meet the species that will benefit from wildlife crossings for I-15.

Sustainable Development

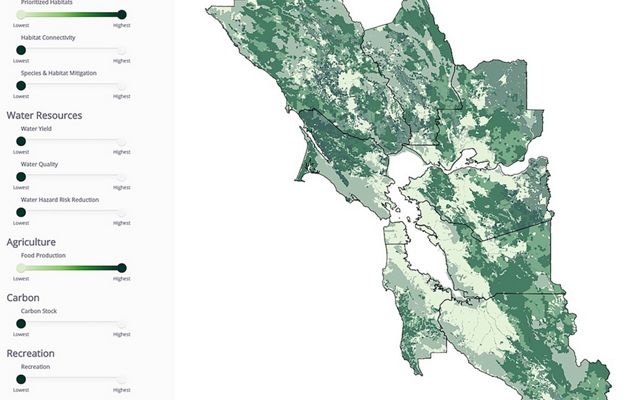

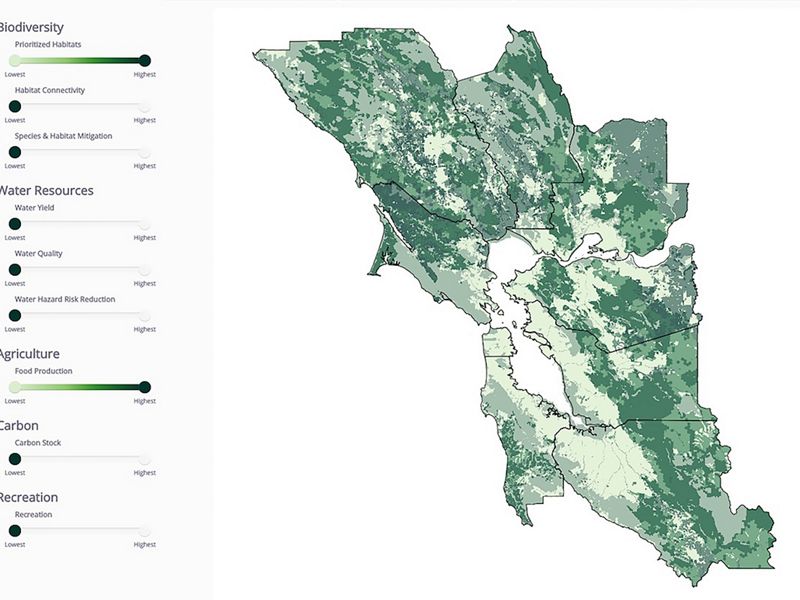

When we plan the growth of our cities and communities, it’s critical that we consider nature. Until recently, when planners mapped out new developments, they considered roads, infrastructure and business corridors. But those blueprints often lacked information about natural resources and wildlife habitat. At TNC, we help cities and communities take natural benefits into account at every stage of development. The greenprint is one example of how we’re helping cities grow with nature in mind.

Why Blueprint When You Can Greenprint?

We’re working with our partners to develop greenprints across California. A greenprint is a strategic conservation plan or tool that development planners can use to reveal the economic and social benefits that nature provides to communities. Beginning with the Bay Area Greenprint, we mapped the nine counties of the San Francisco Bay Area in collaboration with our partners.

The Bay Area plan made such an impression that the Southern California Association of Governments—the regional planning agency that represents every SoCal county except San Diego—requested a greenprint for Southern California. TNC is now leading the development of the largest greenprint ever attempted. Once the plan is completed, 80% of Californians will be living in greenprinted areas.

Greenprint Resources

- Meet the Greenprint Resource Hub: Find historical greenprints, greenprints near you or learn how to start a green plan

- Bay Area Greenprint

- A greenprint for the Pajaro River Watershed: Pajaro Compass

- And coming soon, the SoCal Greenprint!

Urban Conservation

We seek to protect and enhance nature in heavily developed, urbanized areas. We first need to know what nature remains in these areas, and where it can be found. We also need to understand where habitats can be expanded and added, both for the benefit of nature, and of people. Now TNC is putting biodiversity on the map and bringing nature-based solutions to cities, starting in Los Angeles.

Assessing Biodiversity: Upon examination, urban areas turn out to be the home of a surprising variety and abundance of native flora and fauna. But knowing our neighbors is only a first step. We also need to know where greening projects and other land use changes can provide more habitat, enhance urban biodiversity, and yield benefits to people, all at once.

In collaboration with the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, we launched Biodiversity Analysis in Los Angeles (BAILA), a first-of-its kind study that displays LA’s surprising biodiversity, even in its most developed neighborhoods. We followed up with our Planting Stormwater Solutions analysis which identified areas where the benefits of using nature-based stormwater solutions like bioswales and constructed stormwater wetlands would yield the greatest benefits to nature, to water quality, and to social and public health. Our goal is to make BAILA and Planting Stormwater Solutions guides for planners and decision-makers. BAILA and Planting Stormwater Solutions helpsplanners see where nature-based infrastructure would have the most benefit to people and nature, making new infrastructure an opportunity to bring nature back into the city.

Meet Your Neighbors: The Species of LA

Demonstrating what’s possible: Habitat in the Heart of L.A.

We’re showing how nature-based infrastructure can transform an urban landscape northeast of Downtown LA, along the iconic Los Angeles River. The Bowtie Demonstration Project is a great example of a multi-benefit effort that will capture and clean storm water, enhance habitat, sequester carbon, and provide recreational space. Working with our partners at California State Parks, the Prevention Institute and many others, we’re transforming a storm drain into a meandering arroyo, and vacant land into much-needed habitat and publicly accessible open space. In a highly urbanized environment, people need nature and nature needs people to protect and restore it.

Conservation & Public Health

HOW DID THE BOWTIE DEMONSTRATION PROJECT BEGIN?

Elva Yañez: Long before the design phase that we’re in now. Community engagement was the first step toward co-creating this vision. Our primary objective was to better understand residents’ values — values that should inform green infrastructure projects here and elsewhere in the region before investments are made. There’s a lot of mistrust of big projects in marginalized, low-income communities. Agencies and organizations parachute in and out, and the project ends up nothing like the community thought it would; or, worse, it creates green gentrification and displacement.

Jill Sourial: From a conservation standpoint, we wanted to improve water quality and native habitat to help the Los Angeles River, where the arroyo drains. But the community engagement piece is just as important. Before the project began, the question we asked the community wasn’t “What do you think of these project designs?” It was “What do you want your community to look like?” That process needs to start early and establish an ongoing dialogue.

WHAT ARE YOUR GOALS FOR BOWTIE?

EY: Our goal for Bowtie is to improve community health and quality of life in Glassell Park. We approach all of our green infrastructure efforts from a health equity and racial justice perspective. That means making investments in parks and green spaces in historically disinvested communities of color. Glassell Park has an overconcentration of polluting industries, and it’s surrounded by freeways and rail operations. For us, success means involving residents — whose lives have also been negatively impacted by the lack of environmental amenities—in identifying and advancing solutions.

JS: This is a demonstration project, not only for habitat creation but also for how to effectively partner with communities. Both the community engagement and the work on the ground need to succeed for the project to succeed. We want to create a new normal around community engagement so future L.A.-based projects can use the same co-creation model and sustain authentic community involvement.

WHAT WILL THOSE FUTURE PROJECTS LOOK LIKE?

EY: Bowtie is one important piece of a much larger vision for 100 acres of land owned by a number of different agencies. The first phase, Paseo del Rio, is a greenway that will run through those properties along the river and end at Bowtie. Our goal is to influence this work and broader L.A. River revitalization efforts, not just in the design but the community engagement approach, with a strong emphasis on health equity and racial justice outcomes.

Disaster Resilience

Climate change is making natural disasters more intense and severe. Sprawling development is bringing people closer and closer to the epicenters of these disasters: our coasts, floodplains, and forests. When development spreads into areas vulnerable to natural disasters, it limits the protective benefits nature provides to communities and puts people and nature at risk. If we continue to sacrifice nature in favor of development in high-risk areas, we will ultimately lose both.

But the problem is not just about how we plan future growth—a third of all Californians already live on the edge of wildlands. When these communities experience wildfire losses, the most frequent outcome is rebuilding in place, leading to a cycle of “burn-build-repeat.” TNC works at the intersection of science, conservation, policy, and economics to elevate nature’s critical role in ensuring resilience to climate change and delivering solutions at both the build step and the rebuild step.

Fire: Learning from Tragedy

We know that business as usual is leading to bad outcomes for people and nature. Can the solutions for nature also be solutions for people? We believe the answer is yes.

In Paradise, California, we’re working with our partners at the Recreation and Parks District to experiment with open space buffers and intentional planning to help keep people out of harm’s way while restoring habitat. In these early stages, the science is already showing that buffers can work and people can also access the benefits in the form of accessible open space and newly opened doors for insurance.

How can this strategy scale to other geographies? That’s the next question our team is working to answer. CityLab spoke with TNC about the project and the potential to expand.

Coastal: Sea Level Rise

Sea level rise is changing California’s coast. If we want to protect what remains of our iconic coastline, we need to safeguard the coast of tomorrow. We’re leading this effort with the Hope for the Coast initiative, while focusing on high-impact projects to get the job done.

TNC created the Hope for the Coast initiative after assessing coastal habitat across our state’s entire coastline. The joint study by TNC and the State Coastal Conservancy showed that over half of California’s coastal habitats are highly vulnerable to sea level rise. Click here to see how Hope for the Coast quantifies and maps five strategies to maintain our state’s natural coastline.

Protecting natural coastal habitat is critically important, but people also call our coasts home. Nature can reduce risks to communities in the face of sea level rise while protecting biodiversity. One champion in the fight against sea level rise is the US Navy.

Coastal Resilience and the U.S. Navy

Our team is partnering with the Navy to prepare for the impacts of climate change on Naval Base Ventura County, Point Mugu in California. NBVC is a critical and strategic asset for the Navy and home to Mugu Lagoon, the largest and most intact saltmarsh in Southern California. Mugu lagoon supports high biodiversity and many imperiled species like the snowy plover. Protecting and enhancing the lagoon’s coastal habitats will absorb flood waters and buffer the base from sea level rise while supporting this critical ecosystem.

The Navy understands that preserving this coastal habitat will help insulate their assets from the effects of climate change. Our hope is that this type of multi-benefit conservation will become a standard practice from coast to coast.

Other places we’re working:

Elkhorn Slough: Protecting habitat and reimagining transportation infrastructure along the coast.

- Climate Resilience Study.

- Virtual Reality Simulation of sea level rise at Elkhorn Slough.

Long Beach: Partnering with The Aquarium of the Pacific to find out how sea level rise and managed retreat are affecting communities.

- Virtual Reality Simulation of sea level rise in Long Beach

- NPR and Sierra Magazine cover our work.

Ormond Beach: Protecting and restoring Ventura’s future coastline through a community vision.

- Protecting California’s future coastline

Clean Green Energy

Shifting to clean energy production is critical for addressing climate change. This shift will require vast investment in new infrastructure such as renewable energy power plants, electric transmission lines, and batteries. Planning ahead for clean energy infrastructure enables us to build the renewable energy projects needed while protecting biodiversity.

A Roadmap for Clean Energy and Desert Land Protection

California is a leader in pursuing policies that will lead to the adoption of more clean energy in order to reduce emissions and put us on track to meet our climate goals by mid-century. Achieving our clean energy goals will require investments in large amounts of new renewable infrastructure to support a mostly electrified economy. Our studies estimate that California could need anywhere between 1.6-3.1 million acres of land to support our state’s 100% zero-carbon energy target. At The Nature Conservancy, we use our expertise in land management and science to find opportunities to scale up clean energy, while protecting our important landscapes and wildlife habitat.

After California pledged 30% renewable energy in 2008, TNC assessed conservation values across the entire Mojave Desert. We found that our state could meet its renewable energy mandate seven times over while still protecting natural lands and wildlife habitat across the Mojave. The Bureau of Land Management used our science to inform their blueprint for clean energy and land conservation.

The final Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan protects millions of acres of desert conservation lands, and identifies 388,000 acres for clean energy development, with the potential to generate enough renewable energy to power 8 million homes.

The Power of Place

TNC has developed a framework that we’re calling Power of Place to address climate change, improve air quality, and balance clean energy development with protecting natural lands for future generations. In the summer of 2019, our energy team released The Power of Place, a land conservation and clean energy study that evaluates 61 different energy futures for California that all result in 100% clean energy by 2050. We developed the energy futures that come to life in this study with two goals in mind:

- Make sure that wildlife in California and across the West have access to the lands they need.

- Reduce legal conflicts that slow renewable energy development by directing future energy investments to areas with less impact on habitat.

Green Power Goes West

Since California announced the plan to reach 100% clean energy, other states have passed similar laws. Now our energy team is expanding The Power of Place to help states collaborate on cleaner and greener energy across the West. We’re now designing new roadmaps to help the western states plan an energy future that is not only clean but green. Look out for The Power of Place West study in 2021.