Scientists from The Nature Conservancy in Arizona (TNC Arizona) have been studying dry forests in Northern Arizona for two decades. Now—in the era of climate change and extreme wildfires—our research is informing strategic forest restoration by demonstrating how ecological thinning and prescribed burns can deliver significant benefits. Even amid rising temperatures and prolonged droughts, our studies show that ecological restoration is reducing the impacts of dangerous wildfires, rejuvenating water sources, promoting new tree growth and ensuring that carbon stored in our forests over centuries is stabilized.

The Challenge

In Arizona and throughout the West, severe wildfires are linked to catastrophe for nature and people. Every year, more severe fires threaten our communities, pollute our air and water, devastate habitat for plants and animals, and cost billions of dollars. Why are we facing this crisis? The answer is complex. For millennia, frequent, low-intensity surface fires have played a crucial role in sustaining the health of our dry forests, ensuring they sustain wildlife habitat, provide reliable, clean water, filter air, regulate our climate, and provide a range of other cultural and economic services. Yet for more than a century, forest management policies excluded forest fires and removed Indigenous stewardship and the tribal practice of cultural burning from the land. In disrupting the natural fire cycle, we prevented those low- and moderate-severity fires from regularly clearing out small trees and fuels in dry forests. In short, we left our dry forests overcrowded with fuel that causes larger, more intense and more dangerous wildfires. The higher temperatures and prolonged droughts delivered by climate change only exacerbate this legacy of forest management. This problem is urgent and widespread—impacting millions of people as well as economies, industries and plant and animal species throughout the West.

Large-Scale Solutions

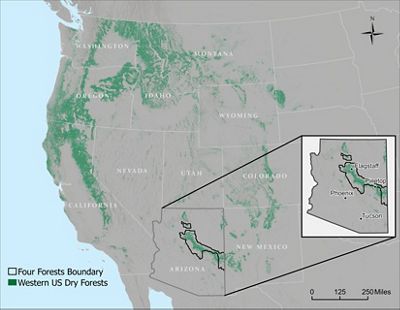

Bringing our forests back into balance and reducing extreme wildfire risks are daunting challenges. In northern Arizona, TNC is partnering with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service (USFS) and other stakeholders on the groundbreaking Four Forest Restoration Initiative (4FRI) to restore 2.4 million acres in the West’s largest continuous ponderosa pine forest.

Thinking Big for Western Forests

TNC Arizona’s involvement in the 4FRI Initiative is a key element within our large-scale vision for increasing forest resilience throughout the West, but it’s not the only place where TNC is working at large scales to restore dry forests. Through our Western Dry Forests & Fire Program, TNC is working across borders and boundaries in 11 states with partners such as the USFS, Tribes, local communities, state agencies and universities to advance public policy and promote best practices to support forest resilience. In the science arena, the lessons we learn through 4FRI and other landscape-scale projects on innovative uses of science and technology are informing efforts by TNC and partners throughout the region.

Science Leads the Way

In 4FRI, TNC’s science team plays a crucial role by providing the best available science, supporting collaborative planning, and working on project implementation and monitoring. The science team also conducts research that quantifies restoration benefits. Marcos Robles, TNC Arizona’s Lead Scientist, explains: “It’s our job to demonstrate if the restoration strategies are actually working—to show whether and how we are making forests more resilient—and to document if benefits are being delivered at meaningful scale to protect people and nature.”

Robles’ colleague, TNC Arizona Forest and Wildland Fire Ecologist Travis Woolley, remembers how the Arizona science team first got involved in the 4FRI Initiative: “It all became real to our science team on a hike in the pine forest here in Northern Arizona.” In 2014, Woolley led Robles, TNC Arizona Spatial Scientist Lisa McCauley, and other members of the science team on an exploration of several forest sites slated for restoration as part of the 4FR Initiative.

What they found that day was a valuable opportunity for new research. “The forest looked like a doghair thicket, with thousands of trees per acre, and one-hundred-year-old trees with trunks no bigger than twelve inches in diameter,” says Woolley. “We were struck by the number of trees and amount of dry fuel on the forest floor, which were so obviously vulnerable to severe wildfire, and we also knew that every one of those trees was drawing water from the soil.”

Woolley and his colleagues recognized that the large-scale forest restoration envisioned in the 4FRI Initiative offered them a massive laboratory to explore key questions about dry forest restoration, such as how are trees competing for water, what level of stress do they experience and how is water flow constricted by a dense forest canopy? Most importantly, though, emphasized Robles: “We realized we had the chance to study and learn where to apply forest restoration treatments at the right place and scale, at the right time and with the right frequency, to yield the most benefits.”

For the success of the 4FRI Initiative and other dry forest restoration efforts West-wide—this type of science matters—in fact, it’s a game changer.

Proving Results—and Benefits

Since that critical hike back in 2014, Robles, Woolley and McCauley have been playing a key role in understanding the successful outcomes of 4FRI’s landscape-scale forest restoration. To date, they’ve worked with collaborators from the USFS, the USDA Agricultural Research Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Arizona University, University of Arizona, Portland State University, Colorado State University and the University of Montana to complete over a dozen studies on the effects of forest restoration and wildfires on forest and watershed resilience. In each study so far, the team’s results show that the restoration is working—and also that it’s providing valuable benefits.

Robles underlines the significance of this discovery, “In my 20-plus years of experience, it is not often that a conservation tool or solution is so effective. Done correctly, ecological restoration can truly change the future of our forests.”

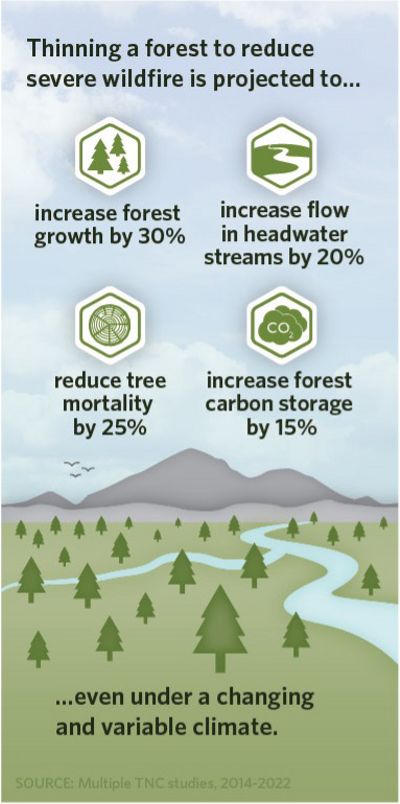

The bottom line? According to the TNC Arizona team’s research, when forests are effectively restored with thinning and prescribed burns, the benefits are significant:

-

Water is saved

Where forests are thinned, more water, potentially up to 20% more, is available to replenish aquifers and seep into streams in the upper watersheds. Again, opening up the canopy of forests allows more snow and water to filter into the soil that feeds streams. In addition, overgrown forests use more water than healthy forests because excess trees act like straws, all competing with each other for limited water. Read the study

-

More carbon is stored

TNC studies show that large-scale thinning and prescribed fire could significantly increase future tree growth and stabilize carbon even under climate change. Initially, when the trees are cut, carbon is lost, but after several years, remaining trees continue to sequester carbon because they are less susceptible to high-severity wildfires. Storing carbon in our forests is a good way to prevent greenhouse gases from further heating the atmosphere and amplifying wildfire activity. Read the study

-

Forests are more resilient to drought and heat

Lower density forests reduce tree competition for water and allow trees to sustain growth and be more resistant to drought, even under climate change. Read the study

-

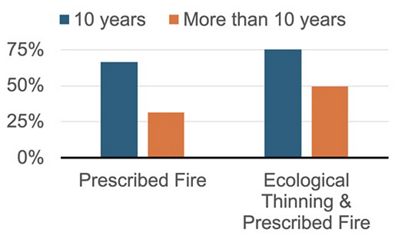

Risks of severe wildfire are reduced

A study of forest restoration in dry forests across the West demonstrates that a combination of ecological thinning and prescribed burning reduces fire severity by up to 70% when compared with forests that were not treated. By reducing the density of the forest canopy, these treatments effectively reduce fuels available for wildfires to burn and spread across the landscape. See the graph below & Read the study

Get the printable fact sheet