Life Below the Surface Artificial reefs boost marine life and restore ocean habitats. © TNC

The work begins in the dark. Before the sun rises, the research team loads gear onto the boat—coolers packed with ice, waterproof cases of electronics and bundles of traps rigged with whale-safe lines. The hum of engines breaks the quiet as they head out from Jones Inlet, navigating toward the Atlantic Beach Artificial Reef off Long Island.

At the reef, the ocean floor tells a story of transformation. Before it was built, the underwater landscape was a flat stretch of sand and mud, with few places for marine life to thrive. Now, it features strategically placed concrete slabs, steel decking, retired vessels and rock piles—some from NYC subway tunneling—that offer crevices and ledges mimicking natural habitat in high demand. These materials are a magnet for black sea bass, lobsters, flounder, porgies, tautog—and the anglers who chase them. One of New York State’s designated 16 artificial reefs, it’s part of a network where underwater structures, both natural and human-made, have become bustling neighborhoods of ocean life.

To better understand how these structures sustain marine communities, scientists must look below the surface.

Innovative Research Looks at Life Under the Surface

Out on the water, the reef is invisible but clusters of fishing boats and pings from the boat’s “fish finder” give it away. The team drops underwater cameras that drift among the rocks, capturing footage of crabs, summer flounder and even a great white shark weaving through the shadows. They collect water samples for environmental DNA analysis, offering a snapshot of the species nearby without ever touching a fish.

Traps are set early and left to soak for hours. When pulled in the afternoon, they’re opened carefully, and each fish is measured, tagged and released. Some are fitted with acoustic telemetry tags, allowing scientists to track their movements across the reef. The data reveals surprising patterns: some fish spend time at the same rock pile for the whole season, suggesting a strong preference for their chosen habitat.

“Fish and lobsters don’t care if their home was built by a glacier or a human,” says Carl LoBue, oceans program director for TNC in New York. “They care about size, location and access to what they need. They’re not so different from us.”

Shipwrecks, bridge pilings and even offshore wind turbine foundations can all offer shelter and feeding grounds, turning infrastructure into essential habitat.

Concrete Solutions: Designing Artificial Reefs to Support Ocean Life

Quote: Carl LoBue

There’s a lot we don’t know about underwater habitat in the ocean. The more we learn, the better positioned we are to protect it—and in some cases, to create it.

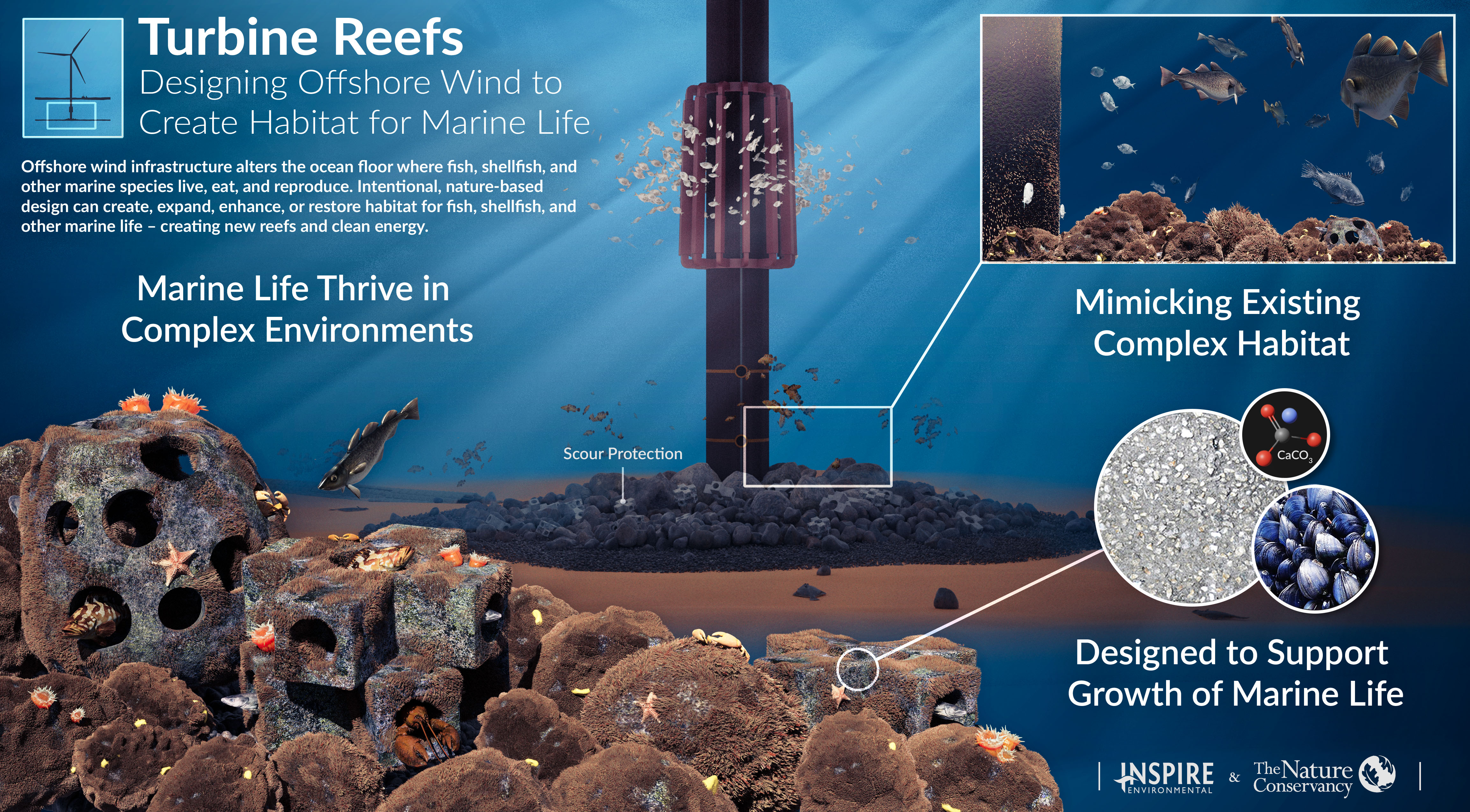

The Nature Conservancy and Inspire Environmental, a marine consultancy, set this work in motion in 2021 with a simple question: Can we design underwater structures that mimic natural reef environments and better support marine life? Their report laid the groundwork for testing materials and shapes that might improve habitat for key species.

But scaling up experiments to match the size of massive built foundations proved costly. And with other variables at play—like how fishing affects local populations—measuring subtle differences in habitat value became even harder.

That challenge sparked this new study now underway at the Atlantic Beach Reef. Led by The Nature Conservancy and Stony Brook University, with support from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), researchers are looking for efficient ways to measure whether nature-friendly designs actually work.

By comparing different monitoring methods, scientists hope to home in on the ones that can most effectively detect small differences in how marine animals use different materials and construction designs to make their homes.

Measuring What Matters: The Impact of Reef Design

Back at the marine lab at Stony Brook University, the detective work continues. Scientists review hours of video, analyze DNA sequences and compare results across different reef structures.

“Every time we build underwater infrastructure, we have the chance to do more than just meet engineering goals,” says Stephen Heck, a postdoctoral researcher at Stony Brook. “We can design these structures to support an incredible array of life.”

“But not all structures are created equal,” he adds. “This research will help us learn whether an approach is working—and whether it’s worth the investment.”

Local Impact, Global Reach

The Nature Conservancy and Stony Brook University bring complementary expertise to the project. Together, they’re working to understand not just how habitat-enhancing designs can attract marine life but how they can sustain complex communities—and how to measure that impact with precision.

“There’s a lot we don’t know about underwater habitat in the ocean,” says LoBue. “The more we learn, the better positioned we are to protect it—and in some cases, to create it.”

This approach—applying ecological design principles to underwater infrastructure—could be a gamechanger not just for habitat, but for supporting the global food supply and local economies.

In the North Sea, Nature Conservancy Scientist Boze Hancock is testing innovative ways to incorporate the nearly wiped out European flat oyster into the design of offshore wind infrastructure. Reviving these once abundant oysters could restore a critical species and ecosystem function. And in small island nations throughout the Caribbean and Indo-Pacific, strategically placed underwater habitats are showing promise for easing diving pressure on natural coral reefs, creating new opportunities for sustainable tourism.

“Healthy oceans and all the things people want and need from the ocean can coexist,” says LoBue. “It just takes a little bit of work. And science can show how to do it.”

Download

TNC & Inspire Environmental found opportunity to create new fish habitat on wind turbines.

Download Explore The ReportWant to learn more about artificial reefs?

Our media team will connect you with on-the-ground team members.