TNC's Silver Run Preserve in Jackson and Transylvania counties is a microcosm of what’s wrong with Southern Appalachian forests. The 1,483-acre preserve is covered with mature oak and hickory trees, but its midstory is dominated by maples and poplars; rhododendron and laurel are creeping up the slopes, setting the stage for an arboreal disaster.

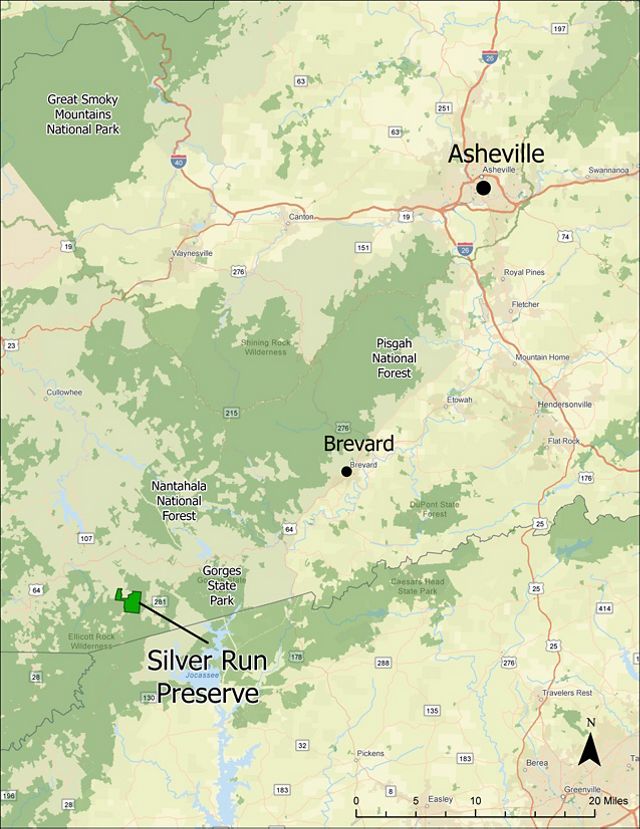

The Wildlife Conservation Society has awarded TNC a grant through its Climate Adaptation Fund, which was established through funding from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. With support from these funds, TNC has begun its oak-promoting work on hundreds of acres of forest that include the Silver Run Preserve in addition to partner lands including the immensely popular Dupont State Recreational Forest and Headwater’s State Forest. Over the course of the next few years, TNC will guide the restoration of thousands of acres of forestland through treatments that promote oak, hickory and southern yellow pine and include midstory reductions and controlled burns.

For many of us, a walk in the woods at Silver Run wouldn’t portend catastrophe. But TNC’s Conservation Forester Greg Cooper and Steward Brian Parr see the future of the forest, and it isn’t pretty. There are few young oaks and hickories and even fewer yellow pine.

“Maples and poplar have their place in a forest, but the midstory in an oak forest isn’t it,” says Cooper. As the oaks and hickories age out, it will convert to a maple/poplar forest. That’s bad news for the many animals that rely on acorns and nuts. It is also not good in a changing climate. Over the past 40 years, temperatures in the region have been increasing at a rate of 0.5°C per decade. Those rising temperatures favor oak, hickory and yellow pine over maple and poplar. Oak, hickory and yellow pine also store more carbon and use up to four times less water than maple and poplar, making an oak, hickory and yellow pine forest more resilient in the future.

That’s why TNC is restoring Silver Run—using the preserve as a living laboratory to illustrate climate-informed forestry that could be replicated across millions of acres in the Southern Appalachians. Restoration will make for healthier forests in the future, but it is also a return to the past.

Duke University researchers have reconstructed the fire history of the Nantahala. They found that fire frequency increased a thousand years ago when Indigenous People moved to the area. No doubt those first land stewards saw how the forest thrived after a lightning fire and started lighting their own fires, removing underbrush and improving hunting conditions.

Fire frequency decreased 250 years ago. European settlers cleared land by logging rather than using fire. In the last century, things worsened. The forest was cleared of large and valuable trees, resulting in today’s uniformly aged forest. Fire was the enemy, and all fires were suppressed. Today’s forest is the result of a century of short-term profit-driven choices and misguided management.

TNC burned a portion of Silver Run this past April. The results were obvious during a July walk. Cooper is pleased with what he sees. “There are tons of red oak and white oak seedlings,” he exclaims.

But burning isn’t enough. Parr points to a young poplar that survived the fire. “These oaks will get out-competed by poplars and maples. They thrive in the understory, and when they get a canopy gap, they just take off. This poplar will out-compete that oak in no time,” he says, pointing to a nearby baby oak. “They will just overtop this tree—knocking back the maples and poplars will give this guy a little bit of a competitive advantage."

Things are very much alive in these restored areas. In addition to the young oaks, birds are thriving and butterflies are winging their way across the burned areas. Parr and Cooper find numerous red efts (tiny newts) thriving in the blackened earth.

Next year there will be another burn, and more trees will be removed. “I have a chain saw, and I will travel,” jokes Parr. With these efforts, oak, hickory and yellow pine will remain the dominant tree in these fire-adapted forests. “Always remember, the future of the forest is in the midstory."

The Nature Conservancy is a global conservation organization dedicated to conserving the lands and waters on which all life depends. Guided by science, we create innovative, on-the-ground solutions to our world’s toughest challenges so that nature and people can thrive together. We are tackling climate change, conserving lands, waters and oceans at an unprecedented scale, providing food and water sustainably and helping make cities more sustainable. The Nature Conservancy is working to make a lasting difference around the world in 77 countries and territories (41 by direct conservation impact and 36 through partners) through a collaborative approach that engages local communities, governments, the private sector, and other partners. To learn more, visit nature.org or follow @nature_press on X.