Time to Fly Gray bats emerge shortly after dark from Bellamy Cave in Tennessee. The cave hosts an estimated 250,000 bats in the summer and 350,000 in the winter. © Stephen Alvarez

At 8:07 p.m.,

a lone gray bat

wheels out of Bellamy Cave

in western Tennessee

and disappears

into the muggy

July night.

Five minutes later, three more flutter out. At 8:26, there’s a steady stream. By half past the hour, the entrance—a sinkhole 15 feet across—is a vortex of flying bodies.

The darkness pulses with leathery wing beats carrying the rush of cold subterranean air, and a quarter of a million bats rise, spiraling into the surrounding trees in a seemingly endless ribbon—the largest summer bat emergence in the eastern United States.

“Back in 2010, I thought I’d never see this sight again,” says Cory Holliday, The Nature Conservancy’s cave and karst program director in Tennessee. “I thought gray bats were done for, that they were something I’d tell my kids about.” He feared the impact of white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that started killing hibernating bats in New York in 2006, and soon after began an unstoppable tear across North America.

Federally threatened gray bats, year-round cave-roosting mammals that amass in vast colonies, seemed to be at high risk, with the majority of Tennessee’s population relying on just four caves for hibernation.

White-nose syndrome takes its name from the white residue it leaves on bats’ faces and wings, but it’s lethal because it wakes bats during winter hibernation—when every calorie counts.

“Bats are nature’s ultimate accountant,” says Pete Pattavina, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service bat biologist. “They measure every energy expenditure and gain, and it’s always a delicate balance for them to make it through winter.”

The waking of an infected bat during hibernation triggers its metabolism and body temperature to rise. Without a food source to offset those costs, the interruption means that the bat runs through its winter energy store and dies. The disease has slashed northern long-eared bat and little brown bat populations by 90% across their ranges. Indiana bats are not far behind, sustaining an 85% decline. Bat populations were hardest hit in northern states, while those in warmer climes (with shorter hibernations) are faring slightly better. Overall, millions have died nationwide.

But, miraculously, the hit to the remaining gray bat populations never came. No one knows exactly why.

Bats play a vital role in our ecosystems. They are key seed dispersers and pollinators, and insectivorous bats can eat one-third of their body weight in moths, beetles and other bugs in one night.

One study estimates they save the U.S. agricultural industry an annual $23 billion in pesticides.

But 15 years after the juggernaut of white-nose syndrome, it’s unlikely that some bats will regain their historic numbers. “A worst-case future scenario is that we see the complete collapse of little brown bats, tri-colored bats and northern long-eared bats,” Pattavina says. “A best case would be a modest increase in abundance, but I don’t expect a big splash of a return.”

White-nose syndrome is here to stay, but so is the new collaborative approach to bat conservation it galvanized.

“White-nose syndrome gave everyone a shared purpose, and that coordination has spilled over to other bat projects, because we don’t take common species for granted anymore,” says Dustin Thames of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, a frequent partner in Holliday’s efforts.

The complicated reality of protecting bat caves

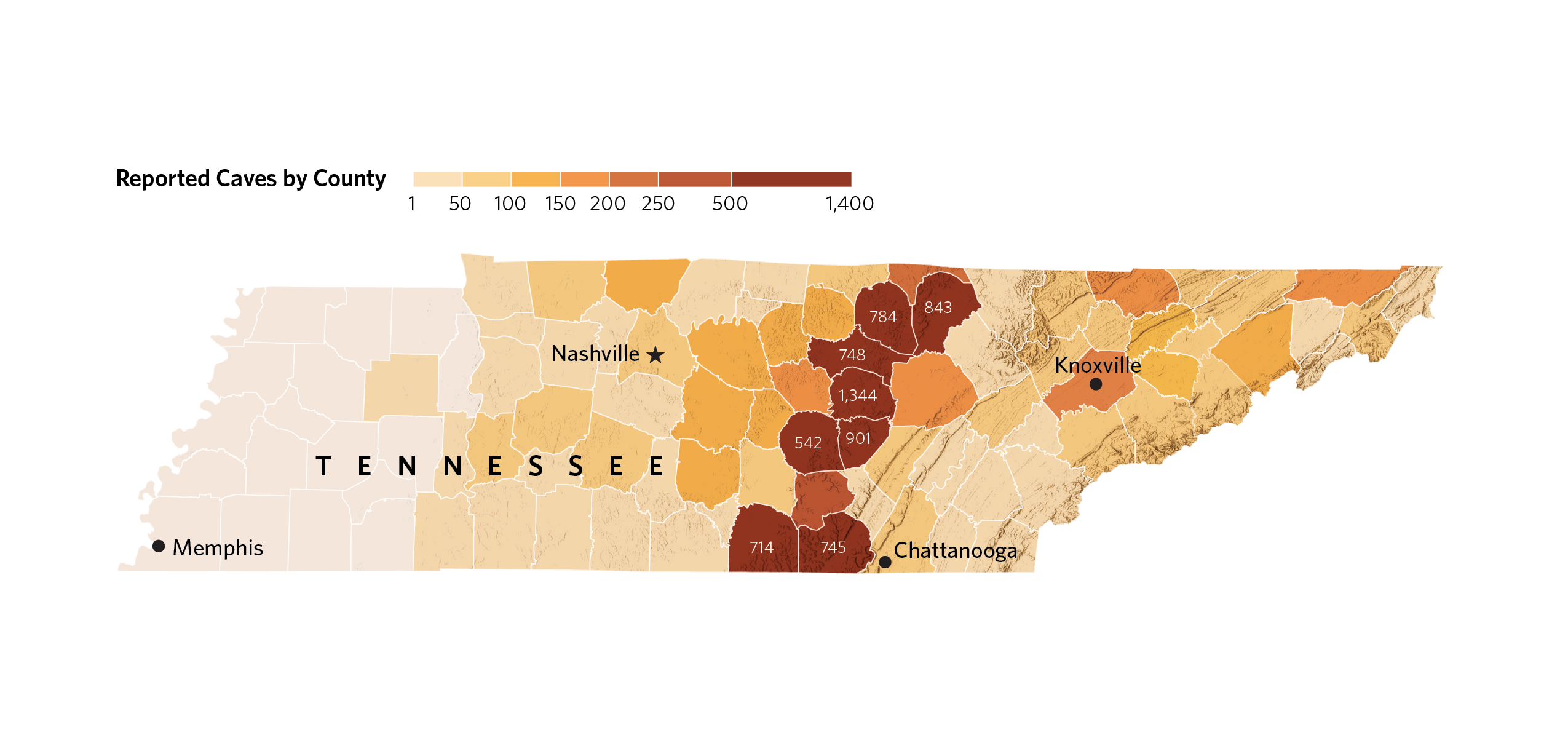

Holliday himself is at the center of Tennessee’s bat action and cave protection. After spending five years surveying life in the state’s caves, Holliday pivoted his program in the early days of white-nose syndrome’s outbreak to focus on bat research and conservation. To protect an animal is to protect its habitat, he says. Tennessee is home to 11,500 known limestone caves, the most of any state in the country; it is a bounty of underground space stemming from the region’s limestone geology.

Tennessee Bats by the Numbers

-

16

Total bat species

-

$23B

Estimated agricultural savings bats provide in U.S.

-

85-90%

Estimated population loss of key bat species

-

11,500

Known caves

-

85%

Caves on private property

Learn More About Bats

10 Fun Bat FactsOne cave Holliday works in represents all he’s up against in these hidden spaces. Like 85% of Tennessee’s caves, it’s on private property. It was once a burial site for Native Americans, and more recently, locals used it as a place to dump garbage. He worked with the landowner to install a gate at the cave entrance to prevent looters from entering to look for Native American artifacts, and to help get it on its way to once more supporting bats.

As in most caves, movement is tricky. When working there, Holliday has to walk, clamber, crawl and belly-inch around the depressions left by looted graves, past possible burn (or smoke) marks from a river cane torch held by an ancient stranger, through a field of years-old guano. Toward the end of the cave, daylight from a ceiling hole illuminates a trash-lined passageway. He’s used to maneuvering through streamers of torn plastic bags, his elbows brushing Coke bottles, a handhold on a tire here, slipping on a beer can there, a disembodied doll leg crunching underfoot.

“It’s out of sight, out of mind for people,” he says with a shrug. “Nobody sees the underside of where they toss this stuff.”

Trash removal isn’t glamorous, but it’s key to restoring caves to support bats. With donor support, TNC was able to buy a different property containing Piper Cave. The cave’s previous owner believed the world was going to end in the year 2000 and transformed it into a Y2K bunker. The cave was outfitted with a camper, survival supplies and huge doors. In the 1970s, 30,000 gray bats roosted there; by 2021 the number had fallen by nearly 90%.

“The first day I got in there, I ripped those doors down,” Holliday remembers. He hauled the camper out with a skid steer and mustered a trash removal crew of state agencies, recreational cavers and the public.

“I thought within a year, we might see a couple thousand gray bats come back,” Holliday says. Instead, he counted an astounding 14,500 in June of 2022. And in 2023, the number rose to more than 24,500 gray bats—a promising sign for a species Holliday hopes will come off the threatened list in his lifetime.

“With white-nose syndrome, we need every bat to make it,” he says. “And every bat is living on the edge.”

Holliday and his partners work to give Tennessee’s 16 species that edge however possible. For gray bats, it’s installing steel gates on caves so humans can’t wander in and wake the animals during hibernation.

For Indiana bats, the state’s other federally endangered species, it’s building artificial roosts so that when they emerge from a cave after a hard winter, there’s optimal habitat waiting.

For northern long-eared bats, it’s hoping to document one at all. And for tri-coloreds, it’s gathering more data to understand how to help them in the first place.

Cave Creatures

Instead of getting its energy from sunlight, a cave ecosystem relies on decaying organic matter from above and on organisms like bats that bring nutrients from the outdoors into the cave. Click to learn more!

Tracking bats in Tennessee for future conservation plans

The spirit of collaboration that’s now a hallmark of Tennessee’s bat work is on display at Bellamy Cave. The Nature Conservancy purchased the cave in 2006, when it sheltered 140,000 bats in winter and 35,000 in summer. Today, after gate installations and protection work by TNC and the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, those numbers ring in at 350,000 in winter and 250,000 in summer.

Tonight, 17 biologists—representing the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, the University of Tennessee, Sewanee: The University of the South and the Department of Defense—are here to attach transmitters to as many gray bats as possible to gather tracking data.

In a nightly summer ritual, the gray bats traverse a mile of Bellamy’s inky passageways, emerging as darkness falls to forage. That is, except for those that hit the harp trap—a device that looks like its namesake, with strategically spaced strings that snag bats who attempt to fly through and deliver them (unharmed) into a trough below.

Two biologists pluck captives from the trough and pop each into a brown paper sack. Runners ferry the bags up a hill to a processing station and clip the bags onto a clothesline. Teams of biologists fetch a bat at a time to record basic information like sex and weight. Each bat receives a tiny forearm band and a transmitter glued on its back. All of this is done on a ticking timer because, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service rules, these endangered bats can’t be held longer than 45 minutes to avoid overstressing them.

Quote

With white-nose syndrome, we need every bat to make it. And every bat is living on the edge.

The data from the radio transmitters is key to learning more about these misunderstood mammals: What are critical habitats for foraging and migration? What are their biggest threats, besides white-nose syndrome?

As the tagged bats fly, they’ll pass Motus Wildlife Tracking System towers dotted across the landscape.

The towers are a recent addition to the biologist’s toolbox; they pick up signals from any passing tagged animal, logging location data that can be easily shared. Motus started as a collaborative way to track birds, but Holliday harnessed its capabilities for bats and has installed 18 towers in Tennessee. The tracking data will shape future conservation efforts, and Holliday hopes it will illustrate where to avoid building wind turbines, a looming threat.

Back at Bellamy, it’s almost 10 p.m.; headlamps illuminate five tables strewn with glue bottles and data clipboards. “We have 15 minutes before we have to release,” calls Holliday. Bags still hang from the clothesline, far too many bats to process as the minutes fly.

Soon, time is up. In total, the biologists have attached 41 transmitters. Those 41 bats will flit across the landscape, ranging 50 miles in a single night, each Motus tower they pass pinging with a data point that’s a window into a secret life. The biologists head to the clothesline, reach into the bags and withdraw the furious little mammals within. They raise an arm, open a hand and cast each bat back into the night, like an offering to the sky.

Magazine Stories in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Nature News email and receive conservation stories each month.

About the Creators

Stephen Alvarez is an award-winning National Geographic photographer who resides in Tennessee. He has photographed ancient cave art around the world.

Lindsey Liles is a freelance writer and full-time editor for Garden & Gun magazine. She specializes in writing about conservation and wildlife in the southern states.