A River Runs Through Us

The Colorado River cuts through landscapes that are as rugged and diverse as their inhabitants. Now, in the face of historic drought, its people are coming together to tell a different story.

Efforts to restore critically endangered black rhinos are protecting a piece of Kenya’s national heritage.

Text by Jennifer Winger | Photographs by Ami Vitale | Issue 2, 2025

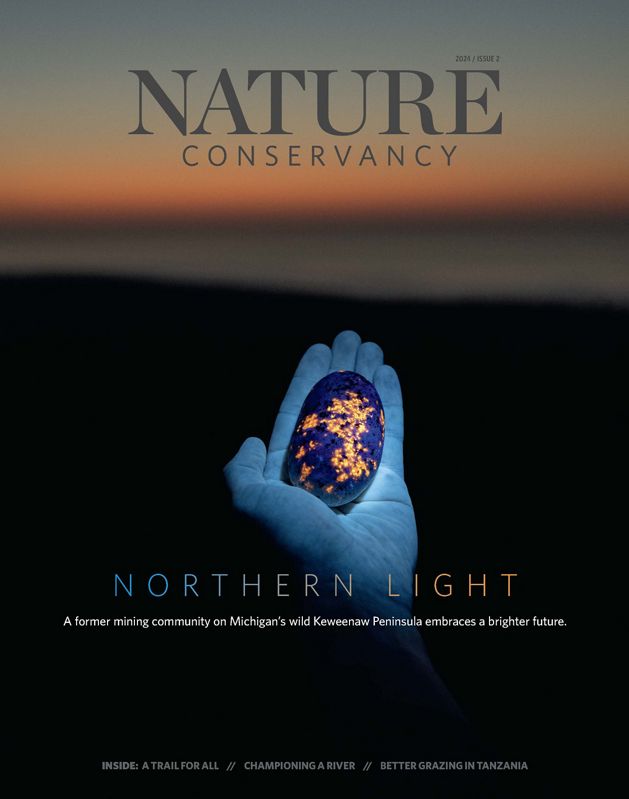

An amber glow illuminates the predawn horizon as David Saruni raises his palm in the air and sends a drone aloft over the grasslands of Loisaba Conservancy, located less than 200 miles north of Nairobi, Kenya. Without the whir of the drone’s spinning propellers, it could look like Saruni is offering a prayer to the sky.

The drone hovers overhead and Saruni, who is a security administrator at Loisaba Conservancy, uses a remote to put the vehicle in something more like stealth mode by turning off the flashing red and green lights. He then guides it up and out over rolling hills dotted with acacia toward an area thick with brush. As the drone disappears in the distance, silence settles over the landscape, punctuated by the songs of spotted palm-thrush and firefinch—and the chirp of Saruni’s radio as other rangers convey reports of wildlife sightings in Swahili.

He is searching for signs of an eastern black rhino and her three-month-old calf. Mother rhinos are fiercely protective of their young, and the rangers here at Loisaba have been giving this family all the space they need while performing daily visual check-ins to ensure both animals are healthy.

Saruni steers the drone by toggling two joysticks above a video screen. Minutes pass as the drone patrols. He stares intently at the infrared video feed, scanning a grayscale landscape that stretches out like a ghostly canvas. Suddenly, two shapes come into focus, each one a blazing white beacon of body heat in the vast wilderness. Saruni zooms in.

Most children growing up in northern Kenya have never seen an eastern black rhino in the wild—and many elders haven’t seen one in more than 50 years. But rhinos were once abundant in the region.

“This landscape is ideally suited for the eastern black rhino,” says Tom Silvester, CEO of Loisaba Conservancy. “If you look at the history, both anecdotal from local people and what was written down by early settlers and explorers, there were a lot of rhinos on this landscape.”

Before the 1970s, some 20,000 eastern black rhinos roamed freely across the country, from the semiarid Tsavo ecosystem to the south to the Maasai Mara landscape in the west to the Laikipia Plateau to the north. But by the mid-1980s, populations had plummeted to less than 400 individuals due to intense poaching for rhino horns. The horns are mainly densely packed fibers of keratin—the same protein that makes up human hair and nails—but are believed by some in Asian countries to possess medicinal properties, and by others to be a sign of wealth and power.

The formation of the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) in 1989 marked the beginning of efforts to slow the species’ decline by implementing anti-poaching measures, increasing habitat protection and creating rhino sanctuaries.

The country now has 17 of these sanctuaries that host more than 1,000 of the critically endangered species. Conservation efforts led by the Kenya Wildlife Service, which have more than quadrupled the population of eastern black rhinos in Kenya since 1984, have been “almost too successful,” says Silvester. The sanctuaries are overcrowded, resulting in increased competition for resources, territorial fights and stress for the rhinos. For the species to continue to recover, new preserves with their own breeding populations must be established, says Silvester.

The latest such spot is the Loisaba Conservancy, which The Nature Conservancy helped create more than 10 years ago, and where rhinos have been absent for around half a century. Loisaba’s permanent water sources, good vegetation and robust security measures make it an ideal spot for rhinos. Still, becoming a sanctuary is no easy feat. The Kenya Wildlife Service requires strict planning, oversight and evaluation of these sites. Silvester and the Loisaba team also wanted to ensure that local communities were empowered to participate in and benefit from the conservation work as well. But if efforts to create a series of new preserves are successful, Kenya stands to not only rebuild a genetically viable population of eastern black rhinos but also reconnect the species’ ancestral landscapes to benefit wildlife nationwide.

In Laikipia, we have seen that when communities benefit from conservation, they become its strongest advocates.

Loisaba stretches 58,000 acres across Kenya’s Laikipia County. Savanna blends with woodlands studded with rocky outcroppings. The Ewaso Ng’iro River, sent from the slopes of Mount Kenya, snakes along one edge of the property. Springs and seasonal water holes support a riot of wildlife: committees of vultures, towers of reticulated giraffes, troops of baboons, prides of lions, dazzles of zebra and now 23 of the country’s eastern black rhinos.

Silvester arrived at Loisaba—then a cattle ranch—in the early 1990s when his wife, Jo, was hired to run the horse stables. He leased the property in 1997 and began transitioning it to become a wildlife conservancy.

When the ranch came up for sale in 2014, Silvester and The Nature Conservancy saw a unique opportunity to permanently protect an ecologically significant landscape that includes critical migration corridors and breeding grounds for a variety of wildlife.

“Wildlife moves between protected areas to conserved areas seasonally in search of water and pasture,” says Munira Anyonge, program director for The Nature Conservancy in Kenya. “The management of these species is therefore a collective effort (communities, conservancies and the government working together) to conserve Kenya’s national heritage.”

In collaboration with local partners like Space for Giants, TNC facilitated the transfer of Loisaba from a private seller to a Kenyan community trust. As a private conservancy, Loisaba would be owned by the trust (rather than the government) but managed for the protection of globally rare wildlife and the benefit of local communities.

Today, Loisaba generates tourism revenue from its 24 high-end tented and open-air guest rooms. Visitor fees from safaris and lodging cover around half of Loisaba’s operating costs and contribute to the protection of wildlife and the advancement of conservation science.

The preserve creates economic opportunities for the Laikipia Masai and Samburu villages that border the conservancy, which include providing more than 450 jobs—everything from rangers to hospitality staff. The property is a hub for regional science and research initiatives (recent studies focused on movement of big cats and reticulated giraffes) with TNC partners, including the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

Establishing a rhino sanctuary at Loisaba not only supports the long-term survival of the species, but also brings the region one step closer to an even greater goal: creating a continuous protected corridor that enhances habitat connectivity for all wildlife.

“Bringing rhinos back to their native habitat is not just about saving a keystone species,” Silvester says, “It’s about restoring the natural balance and ensuring the health of an entire ecosystem.”

In a plain building near the dirt tracks that form Loisaba’s air strip, Saruni and Daniel Yiankere, security manager for Loisaba, study a map of the conservancy and the surrounding areas on a massive television screen mounted to the wall. Software gathers real-time information from ranger reports, individual animals’ GPS tags and in-the-field sensors like camera traps. Transferred via digital radio and satellite to this central operations room, the information is instantly merged with historical data to give a live, comprehensive view of the landscape and its wildlife.

“Software like EarthRanger helps us track the movement and behavior of animals, aids in coordinating ranger patrols, and allows us to monitor potential threats like poaching,” says Saruni.

Keeping watch over thousands of acres is a difficult task, even with rangers deployed around the clock in trucks and on foot. To expand that capacity, Loisaba added a dog-patrolling K9 unit in 2007 followed by a surveillance airplane in 2017, which was a gift from TNC-affiliated donors.

A glance at the screen shows that a seven-year-old male lion could be headed toward a local village and, presumably, its livestock. The security team will alert the community so they can move their sheep and goats or bolster their patrols to ward off the predator.

“Mitigating human-wildlife conflict is a crucial part of what we do,” says Yiankere. “We note where interactions are most prevalent so rangers can develop prevention strategies.”

The Kenya Wildlife Service sets a high standard in security and management for each preserve to qualify as a rhino sanctuary. Properties must submit to a series of assessments to measure disease risk, infrastructure, community support and environmental impact. Stringent ecological analysis was also added in 2019 after 11 relocated rhinos died at Tsavo East National Park. It turned out the animals could

not tolerate the salinity levels in the park’s water.

Loisaba received conditional approval to become a rhino sanctuary in November 2020, but a series of delays, including COVID-19 and flooding, pushed back the translocation. Finally, in the early-morning hours of January 18, 2024, a convoy of trucks carrying two rhinos rolled toward Loisaba. Women from local communities, dressed in brightly colored garments, lined the streets to welcome them.

When rangers opened the first crate, six-year-old female rhino Ushindi ran out into her new home. Moments later as she covered distance, and as a large crowd looked on, three male lions popped up from the tall grass and promptly attacked her, determined to take down a species they had never even seen.

Ushindi survived the assault, and the decision was made to relocate two of the three lions who continued to stalk her throughout the night. The one named Wiseman remains on the property, but true to his name, he has since learned that rhinos don’t make a good meal—at least not rhinos that come with their own security detail.

Despite the delays and shaky start, 21 rhinos from three preserves have been relocated to Loisaba. Silvester says they are thriving in their new habitat.

He recalls watching a rhino cross in front of his truck on the drive home from the first release. “Seeing that footprint on the soil of Loisaba is a moment I’ll never forget,” Silvester says. “For the tribal communities around Loisaba, what you read in animal tracks is a story. So suddenly seeing a three-toed ungulate footprint in your landscape again is a huge thing.”

It’s our national heritage, and we want these animals around so future generations can see them.

Establishing more preserves is just the first step toward ensuring the long-term survival of eastern black rhinos in Kenya. Pastoral communities near these sanctuaries must be on board as well. That’s a big ask when coexisting with Africa’s most dangerous wildlife threatens life and livelihood. Recently, a member of a local village was tragically killed by an elephant. Lions and leopards also regularly pilfer livestock.

“Wildlife is a mobile resource,” says Anyonge, who notes that more than half of Kenya’s wildlife travels outside of government-protected areas and private conservancies. That means local communities play a crucial role in managing these species in collaboration with the Kenya Wildlife Service.

“In Laikipia, we have seen that when communities benefit from conservation, they become its strongest advocates,” says the community programs manager for Loisaba, Paul Wachira Naiputari.

And those benefits are numerous: Tourist stops at local villages drive an average revenue of $17,000 each year. Fees collected from guest stays at Loisaba fund a local healthcare clinic, scholarships for high-achieving students and a food program that provides meals to 4,500 children each day. The Chui Mamas (“Leopard Mothers”) Centre is aiming to improve the lives of local women by providing everything from small-business support, to an organic garden and apiary, to a children’s area and a community room with WiFi.

But for local tribes, the eastern black rhino holds profound totemic value in their cultural beliefs and traditions beyond its ecological role or economic significance. Mathew Naiputari, cousin of Paul, is community conservancy chairman for the Naibunga Community Conservancy Lower Unit, a protected area jointly managed by three communities on Loisaba’s eastern border. He remembers hearing stories from his grandfather, whom he describes as a “lone ranger” dedicated to protecting the last rhinos in the region. Mathew Naiputari says that conserving the rhinos is not only his birthright, but a “collective responsibility” shared by all Kenyans.

“Community leaders and members were engaged from the planning stages, helping to create a sense of ownership and responsibility,” says Paul Wachira Naiputari, who notes that villagers possess valuable Indigenous knowledge of the land and wildlife. Community members also participated in rhino awareness campaigns, supported anti-poaching initiatives, helped build 32 miles of fencing to keep the rhinos in but allow other wildlife to pass through, and are employed as rangers and rhino monitors.

One of the communities responsible for managing Naibunga Lower Unit has even earmarked 500 acres of their own land to connect directly to Loisaba’s property. It will give Loisaba’s rhinos more room to roam while driving visitation to its own eco-lodge alongside the Ewaso Ng’iro River. Additional fencing will need to be installed, but according to Mathew Naiputari, the community has already pledged a number of goats toward defraying that cost.

“We are contributing in this way so the communities can feel like the rhinos are theirs,” he says. “It’s our national heritage and we want these animals around so future generations can see them.”

Back in the bush, the sun crests the horizon, spilling light across the savanna. Saruni taps the handheld screen showing the video feed from the drone, and shades of gray and white shift into color.

“There he is.” Saruni’s hushed tone could reflect the early hour, his gentle demeanor or reverence for what now appears on screen: two rhinos, one much larger than the other, in sharp relief. Three-month-old Valentine—named after the holiday when the community held a celebration for the arrival of the rhinos—sticks close to his mother, Kibou, while they use their pointed upper lips to pluck rough greens from nearby shrubs.

Valentine may be the first rhino born here in decades, but he isn’t the last. Loisaba’s rhino monitors were keeping tabs on at least one other female who has since given birth, and other pairs have been spotted mating—a sign that the 11 females and 10 males, chosen by scientists to create the right mix of lineages for maximum breeding potential, are doing just that.

As climate change makes identifying large swaths of suitable rhino habitat more challenging, collaboration among the Kenya Wildlife Service, conservancies and local communities is more important than ever.

For now, though, confirming that mother and son are in good physical condition is enough. Saruni recalls the drone. It flies back to his open palm, already transmitting video footage of the calf to the ops room, a testament to the hard work of dedicated staff and the foresight of locals who recognize that restoring a piece of Kenya’s natural heritage is an investment in their own future. For many here, it’s a prayer answered. A coming home.

Jennifer Winger is a senior editor for Nature Conservancy magazine, living in Colorado.

Ami Vitale is a photojournalist whose work for National Geographic and numerous other publications has taken her to more than 100 countries around the world.

Sign up for the Nature News email and receive conservation stories each month.