Changing Course

After its fishery nearly collapsed, a Peruvian community begins rebuilding its stocks and planning for the future.

Summer 2019

Five miles off the coast of central Peru, Jose Luis Barron sorts through a pile of sea snails as his small wooden fishing boat rocks and bobs in 6-foot swells. About 10 yards behind him, flocks of seabirds darken the bare dirt slopes of Isla Grande, one of a handful of rocky islands that are part of a protected marine reserve. The air is full of birdcalls and the ammonia tang of guano.

Beside Barron, a rusty compressor chugs away, pumping air into a hose that runs over the side and into the water. About 50 feet down, Demetrio Martinez uses the hose to breathe as he walks along the bottom, grabbing snails and stuffing them into a mesh bag. It’s Barron’s job to sort through the catch, keep the boat off the island’s rocks and communicate with Martinez through a series of yanks on the hose—all at once.

With seas this high, only four out of the dozens of dive-fishing boats based in the town of Ancon came out today. Staying in port can be a tough call, since the fishers depend on selling their daily catch to support their families.

Another fisher on the scene, Rogelio Mendez, says that almost every species here was more abundant when he started 40 years ago: fish, snails, octopus, crabs. “It was like a competition to see who could get the most out of the sea. We didn’t have any discipline, any responsibility to the resource.” Now they are catching less of almost everything, he says.

That’s why The Nature Conservancy has been working with Ancon’s dive fishers for four years, to help them manage their fishing grounds more effectively and ensure they get the best out of what they have. The pilot project is using TNC’s technical experience to help small fishing communities—and eventually the entire country—make choices that will restore their fisheries and keep them viable in the future.

Fishing is a massive industry that employs about a tenth of the world’s population, both directly and through the businesses that support it. It also supplies about 20 percent of the animal protein for almost half the planet. But one-third of the world’s fisheries are overfished, which leads to declining harvests and the possibility of a crash when the sought-after fish seem to disappear entirely. But sustainable management practices—like size limits, catch limits and temporary fishing closures—can rebuild fish stocks while ensuring a reliable catch. These are critical to supporting ocean ecosystems and the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people.

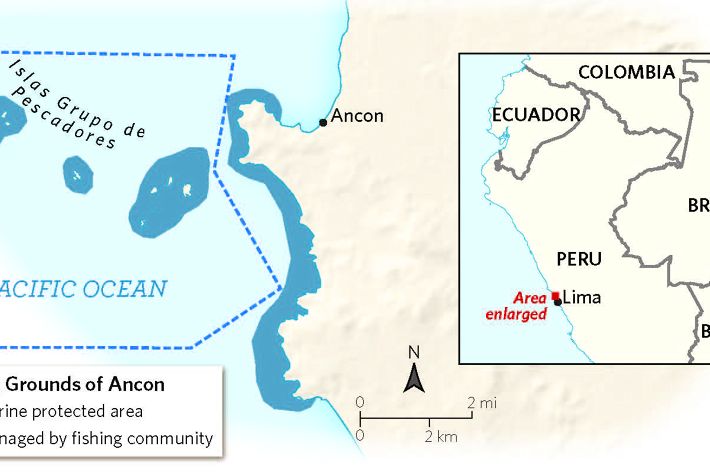

Much of the world’s fishing happens at the small-scale level, and it’s people like Mendez, Barron and Martinez who have a direct and immediate effect on local marine ecosystems. In Peru, artisanal and small-scale fisheries provide almost 80 percent of the seafood consumed inside the country. It’s a physically dangerous and financially risky industry that nevertheless employs about 50,000 people in coastal communities like Ancon, located 23 miles north of Lima. The town’s beaches are packed on weekends, but nearly every day fishers go into the water with lines, nets and air tubes, and return to sell their catch on the municipal dock.

Wider swings in the El Nino and La Nina cycles have affected all segments of Peru’s fishing industry, says Matias Caillaux, a fisheries specialist with TNC’s Oceans Program in Peru. Rougher weather has decreased the average number of days when fishers can go out, and water temperatures are varying more, which can cause populations of sensitive species like octopus to plummet.

Another challenge to Peru’s artisanal fishing industry is that its communities’ waters are open-access, with few restrictions. Communities like Ancon are essentially left to regulate themselves. So when fish populations start crashing, it’s up to the fishers to decide if they want to race to take what’s left or change the way they operate. But economic hardships and a lack of scientific knowledge and hard data can make it difficult, if not impossible, for the fishing communities to come up with sustainable management plans, let alone stick to them.

A complete overhaul of the country’s fisheries management system isn’t realistic, Caillaux says, emphasizing that here decisions are made at the community level—and that’s where conservation efforts need to focus. So TNC is starting to work with tight-knit fishing groups like the one in Ancon, learning the best ways to help them manage their resources before moving to a larger scale. “The ocean has a limited capacity to provide food,” says Caillaux. “It’s not infinite. To create a more stable living for these communities, the first step is stabilizing fisheries.”

Support Science

Science like FishPath is making a difference in our environment and in people's lives.

Sign the PledgeThe Nature Conservancy began working with the fishers of Ancon in 2015. “We decided, let’s start small and learn,” Caillaux says. “If we can’t make it work here, it will be hard elsewhere.” It helped that Ancon’s dive-fishing community, with 65 members, was unusually unified compared with other places, with strong leaders who were already aware that something had to change.

Most of the fishers who operate close to Ancon’s offshore islands are doing benthic fishing, in which divers like Barron and Martinez use “hookah” breathing setups while collecting bottom-dwelling species like octopus, snails, crabs, scallops and limpets, all by hand. They can stay down for an hour at a time, and usually put in three to five hours on the bottom every time they go out. It’s difficult and dangerous work, and the rudimentary gear can cause health problems like decompression sickness and lung conditions.

Around the same time TNC started working in Ancon, the organization and its partners were developing FishPath, a process designed to assist in making management decisions for fisheries that don’t have much historical data. The web-based tool and engagement process uses about 130 questions—about practices such as the amount of illegal fishing and the scale of fishing operations—to recommend the most effective options for collecting fishery data and to suggest ways to raise stock levels such as rotational closures, says Jono Wilson, TNC’s lead fisheries scientist for FishPath. Then it helps users codify those recommendations into a customized management plan.

FishPath is not just the software tool, says Carmen Revenga, TNC’s strategy leader for global fisheries. It’s a system for engaging with communities to help them make decisions for themselves. “The process is the biggest part of it.”

The Nature Conservancy’s immediate goal was to help the divers get hard data on the current health of their local fisheries. Population monitoring happens when conditions are best for fishing: low tide, weak swell and wind, and good visibility. The Nature Conservancy worked with fishers to collect samples of octopus, snails, mussels, crabs and other species.

“Sometimes we go with the [fishers],” says Alexis Nakandakari, a marine conservation specialist with TNC’s Oceans Program in Peru. He works with the local fishing community on a regular basis. “So far they have been OK [with it] since we collect data for analysis and not for controlling their fishing activities.” He says that it’s important to recognize their independence, and adds that the fishers understand that data is critical to making sound decisions.

In February 2015, TNC met with the fishers to discuss octopus biology and the importance of complying with the legal minimum weight limits.

“Suddenly, at the end of the meeting, they started discussing the scarcity of benthic resources in the islands and the need to close one of the fishing grounds to test if it works and how long [benthic species] will take to recover,” Nakandakari says. After some debate, a majority agreed to close one of the islands, called La Isleta, as a test, and asked TNC to help them assess the results.

After five months, the population density of black rock snail had risen by 50% at six test sites. Based on these results, the fishers decided to keep La Isleta closed longer and reopened its waters roughly a year later.

Tracking the average weight and population density of a species—and adjusting the length of closures—makes the process more flexible, Caillaux says. “The idea is that if the average size goes up and density goes up, too, then there is room for increasing the fishing. If those go down, they should also respond accordingly and reduce fishing.”

Quote

FishPath is not just the software tool. It’s a system for engaging with communities to help them make decisions for themselves.

A web-based tool guides an analysis of a specific fishery and suggests effective management measures such as catch limits, gear restrictions and training workshops. FishPath coaches can advise the fishers on how they might implement such practices.

Having access to such information empowers self-regulating fishing communities to make better decisions for themselves. Fishers who help conduct their own monitoring and understand the rationale behind catch limits and other restrictions are more committed to comply with them, says Fernando Ghersi, TNC’s Oceans Program director for Peru. “It’s extremely important to build trust,” he says. “You have to respect their autonomy and be transparent and honest. In the end, they are the ones responsible for the resources.”

It became clear that rotating temporary closures was the most efficient regulation to implement to improve fisheries stocks in Ancon, Nakandakari says. “Closures are very clear and easy to follow; there is no ambiguity or possibility of unwanted error.” The fishers understood that trying to apply rules and limits at the dock, after the catch has been brought in, can create tensions among them and toward inspectors.

As of 2019, roughly half the fishing grounds around Ancon were being closed for one to two months at a time, and stocks and catch per fisher had both increased. Compliance is encouraged through social pressure and fines. Rule breaking is rare but still occurs, especially after long periods of bad weather or before holidays, when fishers need cash more than usual.

In addition to the rotating closures, Ancon’s fishers have been willing to adopt other sustainability practices such as catch limits and size limits. “Now we go directly to a place we have taken care of over time,” says Hector Samillan, president of the Ancon benthic fishers association, “and we take only what we need. The Nature Conservancy has been a great help to us. We had been doing some conservation work on our own initiative already, but we always felt that we were missing something, and I think it was the technical contribution that TNC brought.”

Working with Ancon’s fishing community has had its ups and downs, Nakandakari says, but the overall trend is positive, and the basic lessons are clear. Local fishing organizations don’t have enough money to fund long-term management studies, so technical and financial support from outside organizations helps put management strategies into place.

Helping fishers become less dependent on the vagaries of the seafood market is also important, he says. Among Ancon’s benthic fishers, the enthusiasm for conservation efforts rose when times were good and fell when catch levels dropped.

Since most fishers survive financially on a day-to-day basis without insurance or savings, TNC is also working to identify other activities that could generate alternate sources of income for divers when they can’t go out, such as boat maintenance services.

Even though the fisheries aren’t completely recovered, Caillaux says, catch levels improved during the program’s first two years and remained stable despite El Nino climate events.

Ultimately, members of the fishing community would like to improve their place in the supply chain and receive more money for their catches. “We’d like to get our product internationalized, to directly export to other continents,” Samillan says, sipping coffee with fellow fisher Mendez at a small outdoor restaurant on the municipal dock.

But first they must expand their access to local markets. The dozen or so little seafood stands near the docks buy direct from the fishers, but at the moment only a couple of the bigger restaurants in town—including one named Pepe Cangrejo, run by a former diver—do so. Expanding that list would help the fishers earn more, which is why TNC has been talking up sustainably managed seafood to buyers and chefs in Lima’s world-class restaurant scene. This year, three fishers will take part in an experiment selling products such as octopus, snails and crabs directly to restaurants.

Sign up for Nature News

Get conservation stories, news and local opportunities from where you live.

Overall, the Ancon pilot project has been a success story, Ghersi says. “Fishers have a better understanding of the status of their fishing resources and how their decisions benefit the resource base. They’re also better equipped to establish management commitments as a group and stick to them.” Developing management plans at a local level is a new approach, one that takes cooperation with regional and national authorities, including the Marine Institute of Peru.

“This is not only about fish, it’s about community,” Ghersi says. “Community is where change happens. The question is, how can we design a policy that works with communities—for them to be part of the solution of management and conservation.” The experience at Ancon and other pilot sites will also help the Peruvian government shape a comprehensive policy for community-based management of small-scale fisheries throughout the country, Ghersi says. If all goes well, he envisions that this policy will be formulated by the end of 2021. “It is not a simple process, but we believe this is the way to go.”

In the Ancon area, FishPath’s use has been expanded to develop management strategies for trambollo and Peruvian rock seabass populations, with an overall goal of applying it to at least 12 species in Peru by the end of 2021. The program is also being used in other countries.

Things have been working out well so far, Mendez says, as sea gulls whirl overhead in the salt-scented air. “We’ve learned a lot and continue to learn from TNC. If they’re still here 50 years from now, that works for us.” Today the seas were too high to go out, but tomorrow’s forecast looks more promising.