Artist-in-Residence at Vermont Natural Areas

Elizabeth Billings creates natural installations as an artful and contemplative thank you.

Conservation is powered by people. The Nature Conservancy in Vermont does not exist without supporters like you! Since 1960, your resounding support of nature has allowed Vermonters to seek respite and solace during this challenging year. We hear from many of you that you turn to connections in nature when feeling disconnected from family and friends.

Elizabeth Billings, is TNC’s first resident artist. The engagement was made possible by an anonymous donor who wanted to elevate the relationship between nature and art during an unprecedented year when many found solace in nature. The three art installations take inspiration from the trees, rivers, and wildlife that Billings discovered on her visits to the natural areas during the winter and spring months.

Quote: Elizabeth Billings

“I hope the essence of this work is an offering to the courage of reconnection”

Together: Nature Unites Us

Billings created intentional contemplative spaces at three of The Nature Conservancy’s natural areas: LaPlatte River Marsh, Raven Ridge and Equinox Highlands. These creations, under the title "Together: Nature Unites Us," provide the opportunity for visitors to reflect and connect with nature during this unique moment in time.

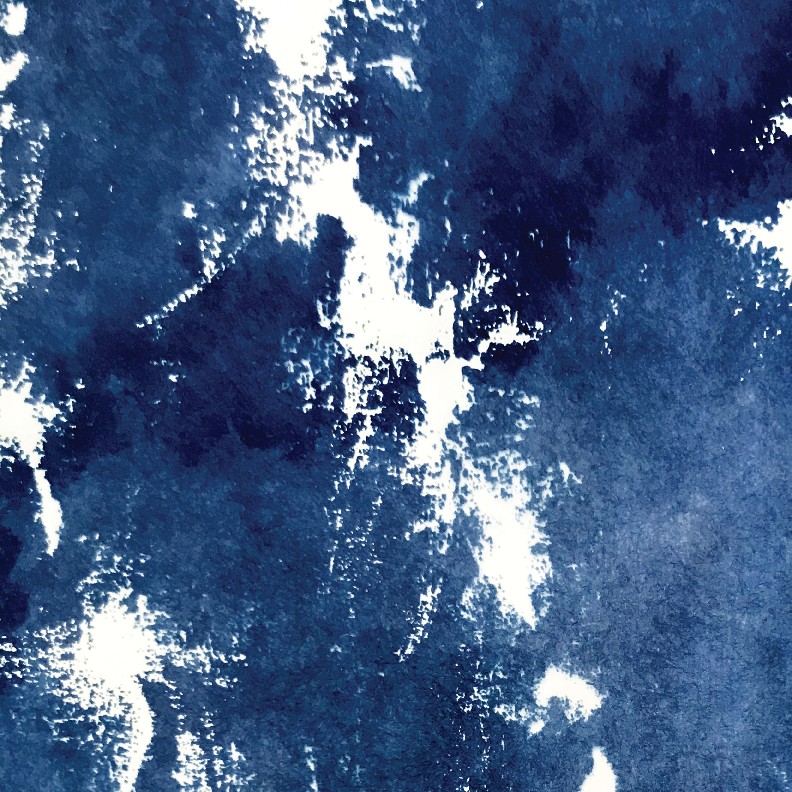

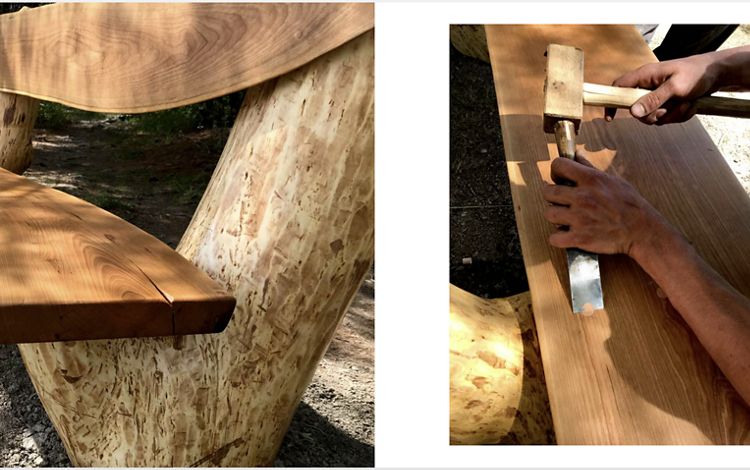

At LaPlatte River Marsh Natural Area, Billings worked with woodworker Mario Sacca to design and install a bench that echoes the curve of the river. Using tree crotches for the uprights and live-edge planks for the seat and back, Sacca created a bench that reverberates the bend in the river while providing a beautiful place to sit. Using tree bark as a departure point and the 180-year old photographic process of cyanotype, Billings created a cyanotype labyrinth that weaves itself in and out and among the tall trees at Equinox Highlands Natural Area. She carried the cyanotype method into her work at Raven Ridge Natural Area where water currents and horizon lines inspired a “blue ridge line,” accentuating the lines of the forest.

From the Field: Fall

I rounded a bend, the path leveled out and I started looking for my old friend. A huge dead standing maple that, every time I pass, magnetically, draws me near.

With a pencil, sketch book and camera in my backpack, I have set out looking for patterns in the woods this fall. It’s a chance to see beyond the surface. The patterns hold me, their endless variety, their ability to seem the same, yet be different.

How does nature do that? Why?

Christmas ferns. Their greenness stands out clearly among the fallen leaves. I started drawing them, and then photographing their silhouettes. Can you see how the fronds attach to the stem at the base, at the very bottom of each single leaf?

I’d never noticed.

Maidenhair ferns. The lace of the woods. They grow where soil is most resilient. They are all over at Equinox, along with wild ginger and ramps, the wild leeks. Does all the diversity, the very health of the soil, change the air? Is that why I feel so happy there?

Tip ups. A below the surface view into masterful intertwining and coexistence. I stare into these glimpses of connection. Or is it disconnection? Or is that just my narrow human interpretation? The tip ups, of course, are not disconnected in the least, they are just beginning another journey, another curve of their cycle. In a healthy forest,

is there such a thing as death?

Birchbark…… What is not to love about birchbark? The peeling, swirling, curling, white, pink, black speckled wonder of a bark. The spirals. Quite simply, they are just plain fun. I’ve brought a gazillion photographs home, like this magnificent one from LaPlatte and I’ve started reverberating the shapes into stitched drawings on vellum.

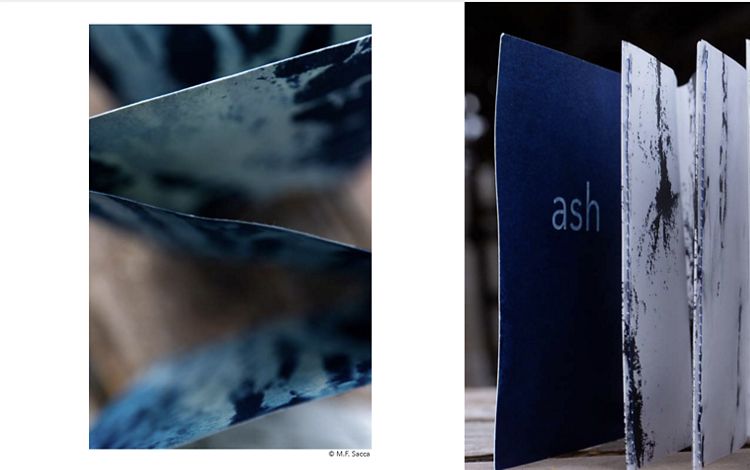

Moving from the bark of the birch, I looked to other trees. And I started making rubbings. Rubbings are an echo of a surface. They give intricate two-dimensional detail from a three-dimensional form. Rubbings illustrate infinitesimal elevations. And there is something a little magical about making them too. I am caught. I’ve made rubbings of beech (like this blistered one), birch, red oak, white oak, pine, hemlock, poplar, shag bark hickory, cedar. And Ash.

I’d like to tell you a story.

I picked up my backpack and started down from the height of Raven Ridge. It was late in the afternoon, and the sun was getting lower in the sky but it was that warm week in October, so it was hard to hurry. The path goes right by a downed ash, a tall tree now horizontal—and that long horizontal surface drew me in. I put my backpack back down, took out the roll of paper and began the process of doing a rubbing.

I secured the paper to the tree and was reaching for the rubbing crayon, when a young family came down the hill. I was on the ground, next to the tree and at about the same height as their young daughter. She looked at me, our eyes met and she asked, “What are you doing???” I explained about rubbing the crayon on the paper—as a way of working with the tree—to make a drawing of the bark. I answered the question but the question lingered.

Her parents and I began talking about the technical aspects: They asked me about the crayons I was using, lumber crayons, made from pigment and clay. They work well and don’t smudge too much. They knew all about them, although not for making rubbings.

Our conversation moved to the beautiful lines of the ash bark—to the straight grain of the wood—and then, to the future of ash in Vermont. I said offhandedly, “And I am doing a grave rubbing.” We all stopped. We just looked at each other. Our eyes welled up and we were filled up, with a kind of grief. One moment spilled into the next, and then the next, as we collectively shared the imminent fate of the ash.

………..

I began visiting the three Flagship Areas when the leaves were still on the trees. They are mostly off now, having whirled their way, round and round, to the ground. The light in the woods has shifted and the shadows thrive. I’ll continue to follow these three places through the winter and on into spring. At the end of each season, I’ll be putting together a journal, a visual journal.

Just before summer begins, art installations will be integrated into each of the three Flagship Areas. I am developing the ideas right now, and look forward to sharing them with you.

Finally, I’d like to close with a poem by Cora Vail Brooks.

It’s titled, “No Two Are the Same”

each steep hour rises

or falls into or out of the next

while we do

what has been left for us undone

Fall Visual Journal

Download

From the Field: Winter

How did we get here?

Last fall, with my backpack and sketchbook, I began exploring three flagship natural areas.

I rotate through them, visiting one each week.

Sketching, photographing, walking, listening, recording, making bark rubbings.

Connecting.

Soon, each of the three Natural Areas will have its own

site-specific art installation.

Being the TNC artist in residence means I am able to be in these places over time experiencing the changes, with the seasons.

And each season is so hard to let go of.

I really, really didn’t want winter to leave:

the clear crisp air,

the snow,

the pared down color palette.

The starkness opens everything up, from views to ways of thinking.

And then, with that first waft of warm air ….

letting go is really not very hard. At all.

Laplatte

In January, I tentatively walked out into the marsh, following deer tracks and cattails through the snow, figuring, not too brilliantly, that if a deer could walk there, I probably could too.

I was lucky, I didn’t get wet.

The further out I walked, the more I could see.

The woods, the river, and the marsh all came into focus, at the same time, and my understanding of the place grew.

I stood on the edge of the frozen river and listened.

The blips, blops, pips, pops, gurgles, and cracks.

I was hearing a symphony of river ice sound.

The curve of the river is the departure point for the Laplatte installation. It will be a live edge wood bench, situated not far from the trail head, and echoing the river curve. The uprights for the bench are tree crotches. I am working with a woodworker, Mario Sacca. He is extraordinary, in my unbiased, objective opinion. He’s my son. We are on target for a late May installation.

Equinox

Here there are snow stripes, Christmas ferns sticking through the snow, and trees leaning into each other, having figured out how to work together, even under tension. And, do it with grace.

The installation for Equinox has gone through a metamorphosis, with each stage harmonizing better, more on key. Murray McHugh, the TNC Stewardship Manager for Southern Vermont, showed me a spot on a spur from the main path, where there is a large flat area overlooked by a ridge. I have sat on that ridge for hours, looking and listening to the place, letting it infiltrate my thoughts and then give my ideas a voice.

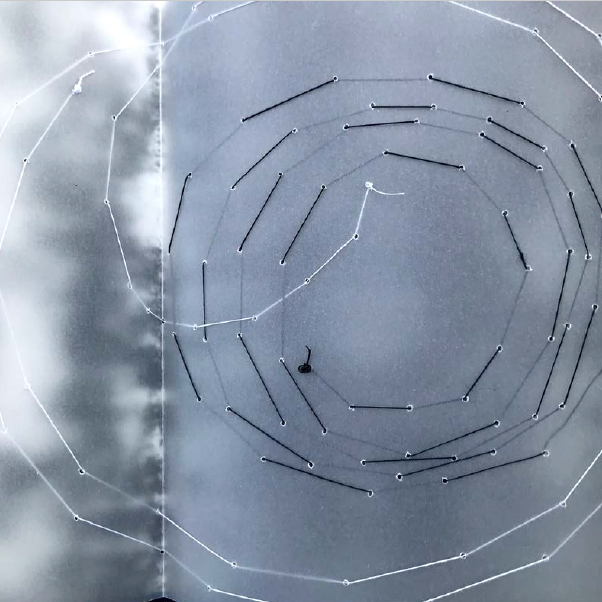

A labyrinth.

What began as a sketch, gained solidity on our kitchen table. After a heavy snowfall, I experimented with the shape and pathways using snowshoes. But the technicalities of translating the sketch have been swirling haphazardly around my thoughts

.

On a recent walk with Jack Markoski, the TNC Volunteer and Stewardship Manager, he asked me if my explorations, the work I have been doing since last fall, were to be incorporated in the installations.

It was a beautiful question. So utterly obvious I know I should probably feel embarrassed, but it sent off amazing synapses in my head. Of course, they should!

And all those swirling tangled thoughts rearranged themselves discovering a clear path forward.

The cyanotype rubbings will become the path.

In the labyrinth, the cyanotype bark cloth will be one foot wide with the top height about two feet off the ground. Imagine the blue curves in the green of summer, or almost covered in snow.

Equinox has a clear and pure voice.

I continue to wonder why. Is it because of its resilient soils?

In spending time in the woods, I stumbled upon a question that has shifted my world.

In a healthy forest, is there such a thing as death?

Raven Ridge

In January, I was at Raven Ridge with a photographer from Seven Days, Daria Bishop. She lives in Burlington but had never been to Raven Ridge.

She loved learning about butternuts, she thought the shagbark hickories were absolutely incredible, and she was generally game to go and do whatever. She helped me measure for the installation that will flow gently above the ground, following the silhouette of the ridge.

She loved the place and has been back, sending me evening pictures of stars through the trees.

These places matter.

This work matters.

How did we get here? How did we get to a world where understanding the conservation of places is essential to survival?

Because we care.

Guided by the Abenaki understanding that people and place are one, we can tell this story. We can share this story.

Art is essential in this sharing. Art has the ability to permeate into our thoughts, our beings, so understanding comes from the inside out.

Art can intuitively, expand our thinking.

Having TNC, a science-based organization, supporting, encouraging and working with art to share this story, our story, is profound.

Winter Visual Journal

Download

From the Field: Spring

Each of the Natural Areas has its own clear voice.

Laplatte is about the innerworkings of all things.

Raven Ridge about the strength, the power in seeing things from differing perspectives.

Equinox holds the whole, pulling us all in together.

I have gotten to know these places partly through making visual journals. The journals are a way of seeing details, looking for patterns, and then looking again. And again. The journals are really a tool, a way to pay attention. The result is a documentation of my meanderings.

I have also been working on site-specific installations, one for each of the three Natural Areas. They were loosely designed last year but as they truly are site specific, getting to know and see the Natural Areas through the seasons has been crucial to their making. With the expert and amazing work of a host of TNC staff, they are now all installed.

I’d like to tell you about them.

Equinox Highlands

TNC talks about resilient soils and their importance in the earth’s resilience to our climate changing world. In talking with TNC’s scientists, I have exclaimed how good I always feel at Equinox and questioned if this is due to the resilience of the soil. With my ever-expanding depth of knowledge and understanding, I am, of course, convinced.

I know I ask the question with more than just a little enthusiasm, and they are kind people, as well as scientists, so they have listened.

And, they have broadened the question.

Resilient soils nurture biodiversity, they encourage growth.

They provide the strongest foundation for our world to prosper. A network of conserved resilient lands is crucial to our survival. So of course, resilient soils give the feeling of wellbeing.

It is what they are.

Equinox was the place I first started doing bark rubbings. Rubbings intricately illustrate what can be so easy to overlook. The patterns that emerge are the universal configurations of mountain ranges, rivers, clouds, watersheds, arteries, and veins.

Are they the voice of the tree?

Are they part of its song?

With the rubbings, I’ve then made cyanotypes, the almost 200-year-old photographic process of coating paper or cloth with light sensitive emulsion, exposing it to sunlight, and rinsing in water.

I’ve made accordion books about trees. A combination of drawings, rubbings and cyanotypes. The books feel as if you are walking around a tree, following its perimeter, and each step, each page, offers a new perspective, another vista, another verse to the song.

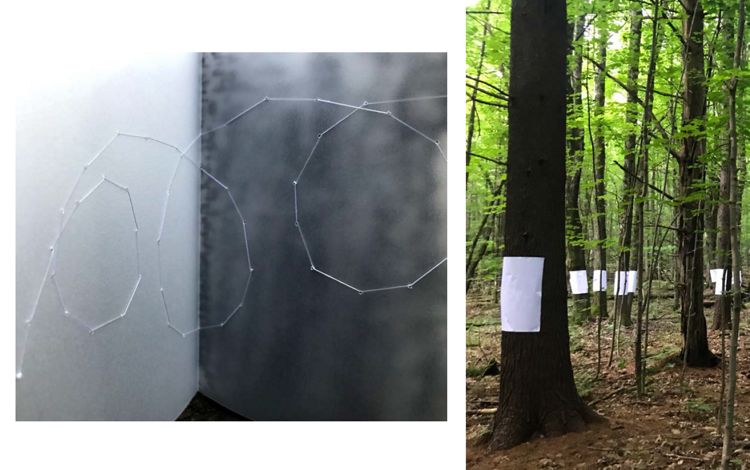

The installation for Equinox is a labyrinth made from bark inspired cyanotypes. The infinite detail of the cyanotype bark rubbings became the path. With TNC staff, we installed the Cyanotype Labyrinth. It went in quite fluidly, and will live in that spot for a year. It is cloth, so it is impermanent. We all are.

Right now, the blue cyanotype bark is striking with the green of spring. I can imagine it with fall colors, peeking out through deep snow, or in among the brown leaf litter early next spring. It will continue echoing the bark of trees and it will no doubt become a little frayed around the edges.

The labyrinth weaves itself in and out and among the tall trees of Equinox. It is quiet. It is bold. It fits in with the landscape but is so obviously of some other.

Because of the pandemic, and nonexistent in-person time working together with TNC staff on the labyrinth was unbelievably special. It was nourishing. We finished the install in a few hours. And then we were held there, for a few more, looking, listening, and talking.

Did the place hold us?

Being together?

Our conversation?

The labyrinth?

I like to think that it was all of the above. That we added something to that place, and together held it until everything came back into balance.

Laplatte

The LaPlatte River meanders broadly before it flows into Lake Champlain creating marshes and wetlands, so important to both river health and the abundant species that thrive there. Laplatte had felt almost small to me. It looked wild but the prevalent urban sounds of automobiles and planes were in contrast to the natural views.

Then winter came. With the land and waters frozen, I began to understand Laplatte’s vast complexity and uniqueness. As with tip-ups, the interrelated systems of the marsh, the chaos and the order, the mundane and the unusual, all were held in what felt like balance.

How does nature do that?

How can we?

The curve of the river was the departure point for the Laplatte installation. I worked closely with woodworker, Mario Sacca, on the initial design of the bench. We shared the pull of the river curve and wanting the bench to belong to the place.

Mario then, took off with the idea, making the uprights for the bench out of tree crotches, curves in their own right. And working with the live edge of the boards for the plank seat and back. There is an ease with the abundance of curves, a harmony.

We installed the bench with Canada geese splash landing next to us. Paddling up and down the river, goslings in toe, letting us know with exuberance who was in charge.

When we stood back to look at this new addition to the landscape, we took a deep breath. It really did feel like it belonged.

Raven Ridge

On a recent early morning trip to Raven Ridge, I was greeted by almost as many red efts as mosquitos. I actually had to put my glasses on as I walked down the path to avoid stepping on them. There were hundreds of them, and mostly teeny tiny ones, about 1 ½” in length. The overnight rain seemed to bring everyone out, with birdsong filling the air.

It was full on spring.

At Raven Ridge, the trail follows along at the base of the ledges with beautiful views of rock outcroppings. The rock formations give a miniscule glimpse of what goes on underneath us, and what has gone on before us.

The formations are monumental; they are a challenge to grasp. Try envisioning the actual forces it might take to bend and shape rock, not carve it, bend it. I can visualize rock moving, but the force behind that movement?

Does it fill you with wonder?

The ledges, with their clear yet amorphous lines were the jumping off point for the installation at Raven Ridge. It is a ridgeline of bark inspired cyanotypes, echoing the silhouettes and contours of the land, zigzagging through the woods, with trees as the connector.

Spending time in and among the ledges, discovering the breadth of the natural of communities, is an education in diversity. From blueberries and vernal pools, to pileated woodpeckers and bear scat. Sometimes it is hard not to pay attention.

The blue ridge line at first seems almost a shadow. There, but not there. Gaining momentum the shadow becomes a line, then many lines, the cyanotype cloth lines accentuating the physical lines of the ledges, resonating with the ridge.

Installing with TNC staff was again, a feeling of emergence and connection. The work went right along and our conversation flowed along with it, a seamless stream of art and science. An absolute joy to be a part of.

The cloth lines overlap, they drift along. The cyanotype blue bark lines are reminiscent of horizon lines, water currents, sap lines, or more than 1000’ of prayer flags fluttering in the wind, hovering above the ground, reverberating the landscape, and woven into the woods.

The three installations are quite different.

The bench, useful in a practical kind of way, a pleasure to rest on.

The cyanotype labyrinth, not what you regularly find in the middle of the woods, yet we are familiar with the idea and we know what to do when we see one.

The blue ridge line? Not useful in the practical sense, and although not familiar, it almost is. We can relate it to things we have seen before but it isn’t really any of them. It is cause for thought, or at the very least, a good reaction.

Why make art installations in nature?

The Natural Areas are beautiful places unto themselves. They certainly don’t need to be decorated.

They do need us to pay attention, to shift our thinking. To care.

To connect.

To reconnect.

Forming special sites along the trails encourages us to ponder, to look and see things in new ways, to look again, to expand our perceptions, our ways of thinking, how we pay attention.

I hope the essence of this work is an offering to the courage of reconnection.

At this time of racial, social, and environmental reckoning and a global pandemic, reconnecting holds us together and inspires resilience.

Because,

we are in a time where the conservation of places is essential to survival.

As with nature, there are all sorts of levels we need to be working on, at the same time.

But the conservation of interconnected lands, resilient wild places, is our foundation. Without a foundation, we have nothing to build on.

Guided by the Abenaki understanding that people and place are one, guided by nature’s interconnectedness of everything, we can understand that we need all of us, the earth needs all of us, working together as one.

We need science to fill us with the how’s and why’s of systems. And we need art to permeate our thinking, from the inside out, with intuition and passion.

And we need everything else, in between, and all around.

Together, we can expand our thinking, our understanding, our reconnection

.

We may not fix everything, but we have to try.

We need all of us.

This is our collective work.

And this work, our work, matters.

The Australian philosopher Val Plumwood wrote:

We will go onward in a different mode of humanity, or not at all

Here are two questions to ponder:

If trees could speak english, what would they say?

If we could understand tree, what would we hear?

View my Spring Visual Journal

Spring Visual Journal

Download

From the Field: Summer

Summer

The three installations, completed in May, now begin their walk through the seasons, a yearlong performance for Raven Ridge and Equinox, and many years for the bench at Laplatte. Each installation has looked so full in the green of summer. Weather is already transforming them, the rain and sun, the changing light, the falling leaves. What will winter bring?

I watch a chickadee sit on the edge of a burl on the back of the bench at Laplatte. Another hops up on the top of one of the uprights, seemingly surveying the surrounding area. The bench is a welcoming place to sit and watch the Laplatte flow by, the kingfisher dive, and the painted turtles sun themselves. The ground in front of the bench is well travelled, letting me know I am not alone in my sitting.

The cyanotype cloth “bark” of the labyrinth at Equinox has become host for the common bagworm moth, hundreds of them. The tiny stick like clumps contrast beautifully against the deep blues of the labyrinth. On both sides of the cloth, the bagworms are small lines of three-dimensional polka dots. An unintended and welcome collaboration. With the summer rains in southern Vermont, almost iridescent lines left by slugs let us know of their travels, up and down, over the cloth.

Bagworms frequent the ridge line at Raven Ridge too. Spiders, take up residence. And in more protected spots, white cocoons intricately stitched to the cloth are in sharp contrast to my own stitches.

The arc of a collaborative process.

Maidenhair Ferns

They draw me in and I have discovered I am not alone in this. Maidenhair look so delicate and light. Their laciness almost belies their strength. I have learned they are indicators of resilient soils and I look for them to help me understand what is underneath, what their roots journey into or out from. There are so many ways to tell a story. What would the maidenhair say? How do we fine tune to listen?

Hermit Thrush

I wait for the song in the spring, and then carefully pay attention as each day passes in August, smiling as I hear it one more time.

I was walking up to the height of land at Equinox and stopped to listen and revel in the sound. I stood and heard one thrush, and then another. Back and forth. My heart sang. I was filled with what I felt was their exuberance. Is exuberance even in their vocabulary?

Then, I began thinking of why they sing and my mind travelled as I searched for answers. My understanding is that birdsong is territorial. The males sing to say, ‘we are nesting here, this is our place’.

What an opportunity for biomimicry. What if we humans followed their lead? Can you imagine the US/Mexican border? The sound of it all? It might be quiet in the fall and winter months, and then burst forth in the spring. The birds do physical displays as well, and we could throw that into the mix. It would begin to feel much more like a celebration of life than a border catastrophe.

The Vermont/New Hampshire border might not have quite the same beat, but we could find a captivating rhythm of sound. Imagine the Russia/US border in the Aleutians? Or the Chinese/Tibet border?

Diversity

Heather Furman writes our “greatest challenges (are) turning the tide on climate change and biodiversity loss.”

Significant to the three Natural Areas that I have frequented this last year are resilient soils and biodiversity. Each place is a cradle, nurturing and caring, for a diversity of life including ours. They are rejuvenating to be in. Looking around, there are hard woods and soft woods, clay soils and glacial till, ferns and fungi, red efts and red-eyed vireos.

Walking through these woods, making bark rubbings of downed ash and blistered beech, contemplating biodiversity loss, I glimpsed a truth that grasps me still. How is it that one of our natural world’s greatest threats is diversity loss, when we are in a fundamental cultural struggle of diversity inclusion? The dichotomy is painful. We understand biodiversity is crucial to our survival. How is our own diversity any different?

Together

In paying attention, we make connections. In making connections, we begin to understand we are re connecting.

It’s all right there, all around us.

Right here.

We need all of us.

Right now.

Summer Visual Journal

Download

Make a Difference in Vermont

To make a gift, contact Catherine Newman, our Director of Philanthropy, or follow the link below.