Holding the Line: Protecting the Sagebrush Sea

Forests are encroaching into sagebrush landscapes, threatening wildlife that depend on sagebrush habitat. TNC and partners are working to address this issue.

A working wilderness of multi-generational ranches and public lands where wildlife and people thrive.

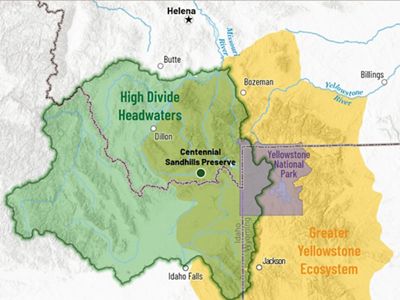

Rolling westward from Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, the High Divide Headwaters is a landscape of wildlife-rich mountain ranges and sagebrush-scented valleys with a proud ranching heritage.

Nestled between the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and northern Montana’s Crown of the Continent, the High Divide provides a vital connection between those regions for grizzly bears and wolverines and hosts seasonal migrations of elk, pronghorn and deer. It’s here that the headwaters of the mighty Missouri River flow clear and cold out of the surrounding mountains. The waters here support a population of rare Arctic grayling, a world-class sport fishery and local agriculture. The region is stewarded by multi-generational ranching families who are the economic drivers of rural Montana and our greatest hope for managing this land at a scale that truly matters.

Our 1,400-acre preserve protects a unique landscape of shifting sand dunes that supports wildlife and rare plants. Learn more here.

Within the High Divide lies the spectacular Centennial Valley, where vistas are still not broken by strings of powerlines. The region also hosts resilient sagebrush grasslands or “steppe” that are unique due to their high elevation.

But the High Divide is under intense development pressure that threatens the area’s biologically rich, intact landscape and rural way of life. The spread of non-native plant species poses another serious threat to the health of native plant and animal communities. The suppression of natural fire cycles has also upset the ecological balance in some areas. Our work at The Nature Conservancy is aimed at conserving this special place and restoring natural systems that have been knocked out of balance.

Among the High Divide Headwaters lies vast sagebrush grasslands, or “steppe,” unique and distinct from others in the Great Basin and Montana’s Great Plains due to its altitude. This high-elevation sagebrush steppe supports a wetter mosaic of habitats, many of which are essential for species that are declining across their broader range, like the greater sage-grouse.

Approximately 90 bird species and more than 85 mammals have come to rely on this high-elevation sagebrush habitat, which, when healthy, is more resistant to invasive plants, has a higher percentage of cover to hide from predators and produces more seasonal forage. In the future, we can look to these places to serve as refuges in a warmer and drier climate.

Yet, wildlife are not the only ones that call the sagebrush steppe home. Ranchers also rely on the remote and wild grasslands for livestock grazing, making this critical habitat a delicate but dynamic working wilderness.

Threats to Sagebrush Habitat

The sagebrush steppe, though resilient, becomes ever more fragile when pressured by human activity. Scientists have long suspected that cattle grazing was one of the primary contributors to the degradation of sagebrush habitat. However, the results of a 2016 study show that “current grazing practices in the Centennial Valley appear to have minimal effects on sage-grouse reproduction and survival during nesting and brood rearing seasons.” That is to say, the typical good stewardship demonstrated by livestock grazers in these high-elevation pastures, such as not grazing in areas when sage-grouse are nesting, has long supported a place where ranchers and wildlife can live in harmony. This is one of the reasons why greater sage-grouse populations are stable in the High Divide while rapidly declining elsewhere.

Rather, the primary threats to Southwest Montana’s sagebrush steppe include habitat fragmentation caused by residential development and exurban expansion. Invasive plants, conifer encroachment and barriers such as fences are also responsible for the loss of these otherwise intact and resilient intermountain sagebrush seas.

Opportunities: Greater Sage-Grouse

The recent success of greater sage-grouse conservation is a testament to how The Nature Conservancy has brought private and public land managers together to achieve lasting conservation outcomes. In 2010 the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service declared the greater sage-grouse as a candidate species for future listing under the Endangered Species Act, an action that granted private and public land managers and wildlife managers five years to put all promising conservation tools to work in order to halt the range-wide decline of the bird. In September 2015, the service determined that protection for the greater sage-grouse under the Endangered Species Act was no longer warranted. This outcome and future protection depend heavily on conservation opportunities and actions.

The Nature Conservancy works in communities across the High Divide to secure a healthy future for the area’s natural bounty and ranching heritage. We have more than 50 years of experience in Montana working with local communities to protect land, build trusting partnerships and lead science-based restoration—all of which have helped us protect and sustain such extraordinary places as the High Divide Headwaters.

The Nature Conservancy is a founding member of the Southwest Montana Sagebrush Partnership (SMSP). This coalition of state and federal agencies, local conservation districts and The Nature Conservancy are restoring and enhancing habitat and working with private ranches to enhance their operations in ways that help both nature and the owner’s bottom line. SMSP can work across boundaries and leverage funding opportunities to conserve sagebrush grasslands at a scale that matters.

Projects include removing encroaching conifer trees—pine, juniper and Douglas fir—that diminish sagebrush habitat, building low-tech structures that slow and retain water, reducing erosion and fortifying wet meadows, and modifying fences to make them more wildlife friendly.

Researchers from Montana State University, in partnership with TNC and the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, spent eight years in the Centennial Valley gathering data on greater sage-grouse populations, nesting and brood-rearing habits, and winter migration patterns. The preliminary results of this project are helping us to understand the impacts of grazing infrastructure such as water tanks, fences and roads, as well as to measure the importance of winter habitat availability for sage-grouse success.

Ranching is not a business for the faint-hearted. There's coping with the whims of weather that may leave a rancher searching for water for their cattle in August or helping a calf into the world in the middle of a blinding April snowstorm. Even in good years, it's hard to turn a profit. Ranching is steeped in tradition, but modern technology may help make things a little bit easier on ranchers and the environment.

Across the High Divide Headwaters, The Nature Conservancy is working with ranchers through the Southwest Montana Sagebrush Partnership to add high-tech tools to their traditional tool bag. And it is ranchers who are spreading the word.

Solar-powered wells and holding basins to collect snowmelt enable ranchers to spread their herds on to more remote pastures, easing grazing pressure on the more accessible areas. Virtual fencing uses electronic collars to direct cattle toward underutilized areas while excluding sensitive areas—all without a physical fence. Virtual fences also help wildlife whose movement can be thwarted by wire fences. GPS ear tags enable ranchers and range riders to monitor their herd's location without having to get on a horse or in a truck to track down the animals.

Third-generation rancher Colt High of the Broksle Ranch is a fan. “We're trying to cut costs and always improve the efficiency, so having this technology helps us better use our pastures and forage,” explains High. “And it cuts down on the labor and really opens up the possibilities of what we can do from a grazing perspective.”

As these new tools show promise, ranchers may become their greatest ambassadors. Through workshops and word of mouth, early adopters are bringing others on board. Eight ranches encompassing more than 250,000 acres have already embraced some form of technology.

TNC and our supporters have catalyzed this movement with information, skills and funding. Our staff scientists, along with partners, are measuring effects of the various tools, both environmentally and economically, so we can quantify their benefits. Those hard numbers, along with straight-shooting testimonials from respected ranchers who have put the technology to the test, will help encourage others to give the tools a try.

Support nature and people in Montana by making a gift to protect vital systems like the High Divide Headwaters.

Explore work across Montana.