Bridges to Biodiversity

TNC is removing stream barriers and clearing the way for free-flowing rivers.

Story by Luke Donovan

In the heart of the Ozarks, streams weave through woodlands of oak and pine, shaping the landscape and supporting a rich diversity of aquatic life. These waterways have flowed for millions of years, forming the backbone of the Interior Highlands region—a biologically significant area that spans southern Missouri, northern Arkansas and parts of Oklahoma.

These streams are home to hundreds of native species, from crayfish and mussels to darters and bass. But their ability to support healthy ecosystems depends on one critical factor: connectivity.

When small dams, low-water crossings, and other barriers disrupt the natural flow of water, they fragment habitats and limit the movement of aquatic species. That’s why The Nature Conservancy is focused on identifying and removing these barriers—to restore stream connectivity and protect the resilience of these vital systems.

Restoring Stream Connectivity

TNC’s review showed that the most disruptive types of infrastructure in the region are small dams and low-water crossings. These barriers interfere with the connectivity of the region’s waterways and put fish populations that are already vulnerable at even greater risk by impeding their ability to breed and find food as they swim upstream.

Though these barriers may look small enough to be harmless, even those that sit only an inch above the water’s surface can severely disrupt the area’s ecosystems.

Quote: Rob Hunt

While trout and salmon in western streams can swim and leap up waterfalls to reach their breeding ranges, many Ozark stream species are unable to overcome obstacles over just a few inches. These obstacles can shrink whole stream systems into 5- or 10-mile reaches to which these fish are constrained.

You may come across a low-water crossing and notice round pipes allowing water to pass through, seemingly allowing fish to pass safely and continue upstream. These pipes, known as culverts, can concentrate flow during high-water events, scouring the channel below. They can also quickly fill with sediment from upstream, causing water to pour over the driving surface and create deep pools on the downstream side of the crossing, creating a vertical obstacle for fish trying to move upstream.

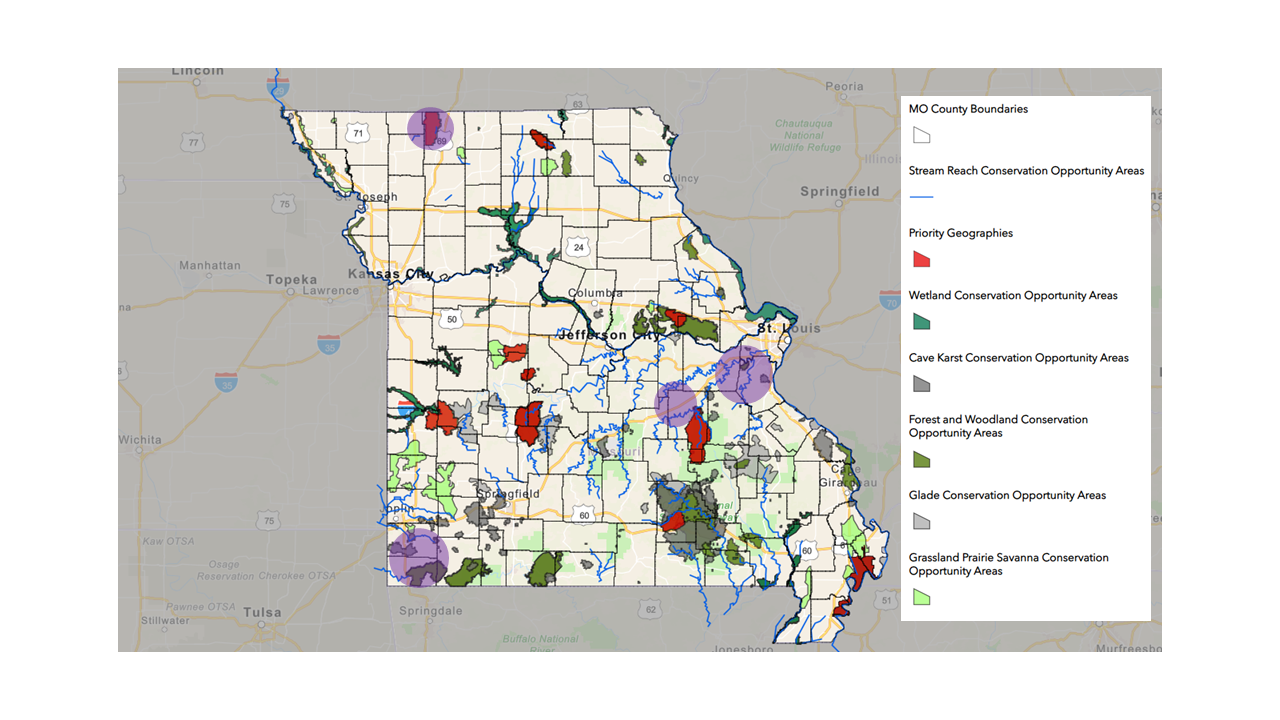

To address aquatic barriers across the Interior Highlands, TNC uses the National Aquatic Barrier Inventory and Prioritization Tool in collaboration with partners like the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and others. This tool helps identify where barriers remain, where they’ve been removed or replaced, and what impact they have on the environment. Efficiency is the name of the game in a region as vast as the Interior Highlands, and this tool helps TNC support the health of these ecosystems in a targeted and lasting way.

Stream Restoration Projects

Eroding streambanks are among the biggest threats to our rivers and streams, dumping tons of sediment and nutrients into the water that harm people and aquatic communities alike. Traditional solutions include added rocks, or rip-rap, along the banks. But there's another way.

Using bioengineering solutions that stabilize banks with natural materials such as trees and live plantings provides better long-term protection and critical habitat for aquatic species to survive. These techniques are commonly used nationwide but are rarely implemented in Missouri.

We've demonstrated these techniques on stream restoration projects around the state with a host of partners, from private landowners to state and federal agencies, to show how we can work with nature instead of against it.

Kiefer Creek

Running through the heart of Castlewood State Park in St. Louis County is Kiefer Creek—a small but important tributary to the Meramec River, which eventually makes it way to the Mississippi River and all the way down to the Gulf of America.

Here, TNC worked with, the State of Missouri, Missouri Department of Natural Resources and Missouri State Parks to stabilize more than 2,000 feet of severely eroding stream bank and improve approximately nine acres of riparian habitat—which is the vegetation and plant communities surrounding the creek.

LaBarque Creek

LaBarque Creek is the most biologically diverse creek that flows into the Meramec River in the St. Louis area. It’s home to over 40 fish species and runs approximately 6 miles before it reaches the Meramec, just south of Eureka, MO.

In 2016, Washington University’s Tyson Research Center contacted TNC to help restore a 250-foot stretch of an extremely eroding streambank on a tight bend of the creek that had dumped over 400 tons of soil and sediment into the creek in previous years. The project was a success and fish monitoring shows an increase in species quantity and diversity.

Huzzah Creek

Huzzah Creek is an ecologically and economically significant drainage in the Meramec River Basin. It hosts a vibrant kayaking and floating industry, providing among best-in-the-state fishing for smallmouth bass. It also supports farmers that rely on its floodplains for livestock grazing and feed crops.

At this site, TNC worked with the Missouri Dept. of Conservation, Ozark Land Trust and a landowner to stabilize nearly 2,000 feet of eroding streambank by implementing bioengineering techniques to stop the erosion, enhance habitat for fish and wildlife and keep private land from washing away.

Elk River

This property on the Elk River lost an astonishing 8,000 tons of soil annually, in total an area of about seven acres in size and ten feet deep.

Working with the Dept. of Natural Resources, the statewide Soil and Water Conservation Program and a private landowner, TNC used bioengineering techniques on 1,600 feet of streambank to stabilize erosion and improve habitat for fish and wildlife, and downstream recreation.

This site is now used to demonstrate to community leaders, private landowners and other stakeholders how about the techniques and how they can be applied elsewhere.

Little Creek

The project at Little Creek had two main goals, stop the erosion that was harming the quality of the creek and fix a perched culvert that was creating a barrier for the Topeka shiner, a federally endangered minnow to migrate up and down the stream for food and breeding.

Now both sides of the creek are re-connected through the culvert using a bioengineered underwater ramp that ensures a more gradual and natural slope. This should allow Topeka shiners and other species to migrate up and downstream to access more habitat.

Alongside the use of smart technologies, collaboration in the region has proven to be crucial in maintaining consistent and widespread barrier removals. Because the region stretches into three different states, collaboration with other conservation organizations is essential. These partnerships allow more resources to be allocated toward safer fish passages, including critical support and funding to finance barrier replacements and removals.

Sherry Fischer, stream and watershed unit supervisor at MDC, is involved in overseeing funds which help to replace harmful barriers with bridges that allow waters to flow naturally beneath. “Most of these projects are really only possible through partnerships and collaboration because of their price tag,” she says. “Luckily, the Missouri Conservation Heritage Foundation’s Stream Stewardship Trust Fund, an in-lieu fee mitigation program, has been able to provide funding for many projects that reestablish connectivity for critical species.”

Read about our work in the Interior Highlands

Learn MoreThe Niangua Darter: A Symbol of Stream Health

The Niangua darter, a federally threatened and state-endangered fish found in only about eight streams running through the Ozarks, serves as an important indicator species for the health of the region’s waterways. They require high water quality to survive, so when barriers and culverts alter the morphology of streams, their fragile populations are put at risk.

Thanks to collaborative conservation efforts throughout the region, however, Niangua darters have become icons of the success of the work being done to remove and replace barriers. According to Craig Fuller, fisheries biologist at MDC, roughly 10 low-water crossings in the Little Niangua River Watershed were cutting off Niangua darter populations from critical habitat. Over a 10-year span, those barriers were replaced with bridges designed to restore natural stream flow and connectivity. The results were clear: previously, Niangua darters were found in only 50% of streams in the area, but soon they were showing up in more than 65% of streams. The species was recovering across the watershed.

It is clear that these projects help to support the health of aquatic life and ecosystems, but they are also vital in promoting more reliable infrastructure for the people in the region who depend on these low-water crossings for safe transportation. Many of these crossings in rural communities are no more than concrete slabs laid across the river’s foundation and are prone to degrading during high waters and flood events. When these bridges are impassable or damaged, these communities may become cut off from emergency services, medical care and school bus routes. It’s important to continue replacement and removal efforts across the region, not only for the well-being of its water systems, but for local communities.

“The most common road-related barriers to aquatic organisms are found in rural areas because these types of crossings are usually less expensive to construct,” says Emily Moyer, resilient waters program manager at TNC in Oklahoma. “But, they often require more maintenance and have a shorter lifespan than fish-friendly bridges and box culverts. When these become barriers, the native stream morphology changes, which can become a battle against nature, causing more maintenance and shorter lifespans for crossings.”

Quote: Emily Moyer

TNC is working to change the norms of using past practices and to share new ideas about more effective solutions. We're partnering with conservation groups, as well as a variety of road managers, including counties, Tribes and the local department of transportation to accomplish our goals.

There’s no easy path to barrier removal in the Interior Highlands, but TNC’s persistence and partnerships help bring renewed hope to the region’s waterways. Every single barrier that is removed or replaced strengthens the ecosystems and local communities by creating safer infrastructure, reconnecting habitat and restoring natural flow that allows these beautiful streams to run freely.

Sign up for Nature News

Get conservation stories, news and local opportunities from where you live.