Reconnecting the Missouri River Floodplain

The construction of a levee setback and development of a playbook to share experience-based lessons.

Flooding has always been a part of Ryan Ottmann’s life. “I’ve lived on the Missouri River my entire life. I still live in the house where I was born,” he says.

Some of his earliest memories are riding in the back of a pickup truck with his dad checking for holes in the levee. “High water events were family events—whole community events, actually.”

The first significant flood of Ryan’s life was in 1993. “The flood of ’93 was bad, and the flood of 2011 was a little worse,” he said. "But the flood of 2019 was exponentially worse than all the other floods combined. I live right on the bluff, and it was water from bluff to bluff for 200 days—and damage beyond belief."

That’s when he realized that they had to do something different for the community now, and for the future.

Download

Learn from the experiences and read recommendations from the L-536 project partners.

DownloadMoving a Levee on the Missouri River

Listen to this episode of TNC’s podcast, It’s in Our Nature, to hear from TNC staff and partners about this project.

Opening: You’re listening to It’s in Our Nature, the podcast that celebrates the connections between people and nature. With host, Adam McLane, The Nature Conservancy’s Missouri state director. For more information, visit nature.org/missouri.

Adam McLane: Hi everyone. I’m Adam McLane, Missouri state director for The Nature Conservancy. Thanks for joining us today. This is episode number three of our podcast, where our goal is to share stories that highlight the connection between people and nature...and the amazing things that can happen when we work together. And if there was ever a story to tell that falls into that category of amazing and people working with nature, instead of against it, this is it. We’re excited to be a part of this project and excited to share it with you all today. But before we get started, one request, it’s the request I always give in these podcasts. If you like it, please pass it along to somebody else. Joining me in the studio is Barbara Charry, who is our floodplain and nature-based solutions strategy manager in Missouri; and joining us via zoom - on the other side of the state is Corina Zhang, who’s an engineer with the U.S. Army Corps Engineers - Omaha district; and Regan Griffin, who’s a board member of the Atchison County Levee District. So today we’re going to talk about how these people and a host of other partners and community members moved to levee. You heard that right...we moved to levee! So let’s jump into it, Regan, well first thanks for joining. And second question-wise, just help us all understand Rock Port, where is this place? Just take us there. What’s the community like. What makes it special?

Regan Griffin: Yeah. Yeah. So Rockport is in the very Northwest, well, actually first I want to say good morning. Thanks for, thanks for having me on, but yeah, Rock Port’s in the very Northwest corner of the state of Missouri. It’s funny actually, when you talk to some folks when you start talking about how far up it is, they think, well, wait, we’re still in Missouri at that point...cause we’re, we’re our closest big city is actually Omaha, Nebraska. So

Adam McLane: That’s right…you’re almost near Canada, I think. Is that right?

Regan Griffin: Yeah, we can, you know, I can see it from my house. As someone once said. But yeah, you know, it’s, I feel like it’s one of those towns that’s like all the country songs, which is why I think people in small towns like country songs, cause there’s one traffic light you know, just everything revolves around the school or revolves around life, in the small town. You know, it’s, I think the big thing that makes it special town is very bonded together. I know we’ve been kind of growing up here as a town where it felt like we supported the youth well, and we still do just a town that cares for looks after each other care for one another. Just love to love to be people who are good to one another. So I think that describes it well.

Adam McLane: That’s awesome. Well, on the country theme, do you have a dog and a truck?

Regan Griffin: (Laughs) No, I have a truck I haven’t got a dog yet, although my two daughters want us to get one soon, so I’m sure that’ll happen

Adam McLane: (Laughs) Very good, thank you. And you, you help run your family farm there. Is that right?

Regan Griffin: Yeah. Yeah. I just came back in 2018 to take over Griffin Farms. So I’ve been doing it...my family has been in the farming business for about a hundred and well since 1860. So a fourth manager in that time. So it’s been a long time.

Adam McLane: Wow. Okay. And then I’m also going to jump over here to Corina. So Corina welcome. Do you want to introduce yourself just a little bit and then I want to hear about how you were brought onto the project.

Corina Zhang: Yes, good morning. And thank you guys so much for the opportunity to come and chat with you guys. And it’s like, I’m getting to hang out with all my good friends here. And yeah, great question of when we, when I was brought onto this project. So I was brought on you know, pretty early in the project. So I worked with the Corps and my role was one of the resident engineers. So I’m on the construction side of the Corps. And one of my earliest memories I remember was actually working with Regan and it was a bunch of us engineers and I think it was like the levee district. And this was after we had decided you know, realigning, the levee was a good idea or setting it back. And we were in like this little office and somebody like put a Sharpie in somebody’s hand and said, okay, where would you draw it?

Corina Zhang: (laughs) And we were, we were looking and trying to draw out like, so what would, what makes sense? And you know, I remember talking about all of the real estate and all of the different landowners, you know, being part of the conversation. And I remember talking to to a few people and people’s faces were like, oh, that’s not gonna work about alignment’s not gonna work. And and then when we finally landed on it, we started moving forward. But that was probably the earliest one we were just thinking about, would this even work? Is this gonna, this is gonna work.

Adam McLane: I’m mindful that I’m sitting here thinking like we’ve had this, we’ve talked to this language for two years on the project, a levee, a levee district, a levee board, a setback, a all of this stuff. And I’m mindful that a lot of the viewers or the lot of listeners probably have no idea what we’re talking about. So let’s do that together and then kind of deep dive into the project and the set. So maybe I’ll go back to Regan. Regan, would you just tell us what a levee district is and how it comes into play within your community?

Regan Griffin: Yeah, yeah. So the Atchison county levee district are responsible for the 56, roughly miles of levee that sits along the Missouri river, which is all along the west side of our county. And so we were formed in the late 1940s, early 1950s as the federal levee program was getting started. And so originally the group was there to basically kind of work with local landowners to say, "Hey, where can we build this levee?" Kind of like Corina we’re saying, get the Sharpie out, but back in the forties and fifties and say, where do we want this levee to set and work with local landowners to compensate them for that ground. And then since that time, it’s the levee district or levee board’s job to continue to do maintenance upkeep of the levees. And then a big piece is just the, the personal interactions and the connection of the Corps of Engineers who you know, basically is the, the arm of, you know, making the levee’s work and, and continuing to make sure that they’re all protected.

Adam McLane: Awesome, all right. And then before even getting into the project, you know, I kind of skipped us ahead. So I’m sorry about that Corina. I was like, "let’s get into the details of the project", but why, why, why was the project even needed? Why did we have to draw things on a map and say, will this even work? Talk to us about the flood of in 2019 Regan or Corina.

Regan Griffin: Yeah, I mean, you know, the 2019 flood was, I mean, by far the worst flood we’ve experienced in Northwest Missouri. We had one in 2011. It was interesting, there was a meeting in November of 2018 where John Remus, who is chief of, I can’t remember his title, I’m sure Corina can correct me, but he basically manages the river Missouri river for the Corps of Engineers. But he had a meeting in November of that year and a lot of local farmers and levee district people at the time got together. And I remember over and over people saying, this is like, it feels a lot like the fall of 2010, which 2011 was the last really bad flood we had. And so there’s already some sense of, okay, 2019 could be a bad year. A lot of the soil was very saturated, had a lot of water on the levees the previous year.

Regan Griffin: And then that that winter through 2018 to 2019 had a lot of snowpack up north. And so there’s some apprehension. And I mean, even the Corps was warning that this could be a really bad year. And then in March of that year is when the bomb cyclone hit, which just absolutely dumped a ton of rain on the area. Melted a lot of snow know that was already expected to hit, but then all of a sudden hit at one time. And it was just a kind of a perfect storm that, that really nailed us at that time.

Adam McLane: And what, how, what did, how long did it last that flooding, and what was the impact on the community?

Regan Griffin: Yeah, well, so I mean the original hit was in about March 15 when the waters first started over-topping to our levees and, you know, probably had our first breaches within about three or four days of that. And so that was March. I mean, we had floodwaters at least to October, November in certain areas. So it was it was the longest flood we’ve ever experienced. I mean, usually, you know, when you’re talking to maybe a few weeks of that, but I think it was an all six plus months of water in some areas standing, which was just really, really devastating. I mean, we’re an agricultural area. So, you know, a lot of the places that were hit were farming you know, for farm ground, but, you know, also just even we have a local elevator that was flooded and absolutely destroyed, and a lot of ways took a lot of money to build that back.

Regan Griffin: And then just other businesses the railroads, another thing BNSF has a railroad that runs right through the middle of our county. And that was shut down for a long time, which, I mean, the think you’d solve it, there’s always BNSF guys out there trying to fix that. Cause I mean, that’s kind of a main artery through the center of the country. Even shipping coal. I know there for awhile, I’d heard the stories. I’m not for sure if it’s fully true, but they’re responsible for bringing coal into certain cities for powering them. And I think there’s a, there’s talk for a while even the federal government having to basically kind of takeover to help with that. Cause they were worried that they could get to the places they need to. So just a lot of, a lot of stuff was, was on the ropes at that point.

Adam McLane: Wow. Barbara, I remember, I think you driving through that area, right. Weren’t you traveling at that time?

Barbara Charry: I was, I was coming down in May from a high school graduation visit and saw all the flooding and I’d heard about the flood in March and it was May, and it was like looking out at a lake and I said, this is supposed to be a river. I was blown away and I-29 was still close in some areas and we had a detour around yeah.

Adam McLane: And grain silos.

Barbara Charry: Yep, grain everywhere. It was, it was really devastating and, and really made a big impression on me. Yeah.

Adam McLane: Yeah, wow. Okay. Well, we get to get to the uplifting part of this whole thing. Cause I know that was tragic and had a tremendous impact on the community and Corina then gets to step in and say, okay, let’s pull that Sharpie marker out. Let’s start thinking about how to repair this right, Corina?

Corina Zhang: Yeah. And to help give folks an understanding of what drove, like why did it make sense to set the levee back? The Corps of Engineers the, the levee systems are driven by public law 8499, also known as PL-8499 and the damages really drive the technical solution that the Corps executes. And when we think through, as an engineer, you think through, you have a problem and then you have variables and constraints, and then you think of what are the solutions to that problem. And so when, when we were approached with this problem, the levee itself, the old levee was so damaged that when we considered well, what would be the least-cost and technically acceptable solution actually making a new levee started making sense. To give some context, the, the old levee on a levee system, L-536 that the Atchison county levee the overall damages for the existing levee was over 11 miles, if you included all the breaches and all of the damages to the old, the old levee system. So when we were thinking about it over 11 miles damage, and then you compare it to, well, what if we built a new levee and that’s about the new alignment was four and a half new miles of levee. You start thinking that could cost that could cost less. And when we did the analysis, that’s what ended up making sense. And so what was really risky though, was taking a strategic pause and saying, well, that means we’re not going to close the breaches right away. The other levee systems, we started initially just closing breaches one after the other, but in order for this to stay the least cost, technically feasible solution, we, we took a year to develop the real estate of what that new alignment would look like. And so that took some time, but we all collectively agreed that even though that risk is worth this investment essentially. And so when, when everybody was on board with that, knowing the risks that, okay, we’re not going to close the levee breaches, but we are going to make this new levee. And the levee sponsor was on board. You know, the community was on board. All of our local stakeholders are on board. So that’s when a lot of momentum started happening. And and it was really cool to watch everybody like come together, but it just, we didn’t skip a beat, even though there were a lot of challenges as I’m sure Regan and Barb could talk at length about.

Adam McLane: Well, and I just for cause I, it was, so I knew all about this project and I had seen aerial photography and images and all sorts of things, but until I actually got there to see the size and scope of this it is really, really something. And it’s hard to capture in words, but in terms of a levee setback, trying to make that a familiar, or breeched even to a levee, familiar to the audience, I did a lot of sand castle building in my days by the ocean. And so you build this giant wall for your sand castle and you had your little front entrance and then the tide would start coming up a little bit and slowly but surely that just starts getting undermined. And then finally, boom, it blows out. So that’s a lot of what would occur with a levee, right? And then, so we moved the sand castle back by 15 feet. So that, that tide wasn’t going to get there or when it did, it was just going to barely be touching. And is that an accurate capture to the general public? Other than it not being an ocean and it’s not sand...I get that.

Corina Zhang: I love that analogy. Yeah, I was actually talking to one of my colleagues, Lowell, Lowell Blankers, he’s another engineer. And he said, you know, the, the simple engineering description is "you moved the levee." And so if you, yeah, like you’re a little like the sand castle, you can, you know, almost you know, if you pinch your fingers together, when you look, you know, close to your eye and you, you, you pinch it and then you move, it that’s really what happened to the levee. And it seems very simple, but when you start thinking about all of the different things that are involved in order to make that happen, you have to find a lot of, a lot of dirt, essentially, a lot of material that’s clay, that’s sand, that’s top soil. There’s a lot of real estate coordination. There’s environmental compliance that needs to happen. There’s contractual obstacles that happen, or just writing the contract in general. There’s creating a new foundation that also has to happen for the new levee. So there’s a lot of there’s just a lot that goes in. It’s not just a, you know, pitching it with your fingers and then moving it. There’s a lot more that goes in. And for some context of the amount of material that was moved the, the new levee alignment took it - we’ve moved almost 2 million cubic yards of material. And just for some context that would almost fill the AT&T stadium where the Dallas Cowboys meet. So that’s a, it’s a lot of, a lot of dirt...a lot of dirt.

Adam McLane: Thank you for that description, Barbara, I’m going to pull you in here too. Cause I think, you know, as Corina described that moment in time where it started making sense that it was possible that a levee setback might be feasible and economically viable in this situation, that’s kind of when the about at the time you got pulled in, does that sound right?

Barbara Charry: We were pulled in really pretty early on, I think it was June when we started the inquiries that, you know, one of the big issues for a levee setback is a need for real estate, you know, for the new footprint and then all the land that’s going to be on the riverside of the new levee. And so that was a big consideration and, and a big problem to solve. So that was the initial reason we were pulled in. And it just seemed like such a compelling idea and such an incredible project that, back in August of 2019, I pulled together a whole bunch of partners to say, okay, this is an incredible idea and incredible opportunity. This is something that community really, really wants. How can we all come together and make it, make it work? So we had started having that discussion in August with that meeting in St. Joe. And then we continued to meet, and that was kind of The Nature Conservancy’s role is, you know, trying to help figure out the real estate component and then bringing people together and convening meetings. And we just started meeting regularly in small groups and in large groups and encountering problems and, and challenges and figuring out ways to address them as we went on, you know, month by month through the process.

Adam McLane: That’s awesome. So this is a huge project. Were there moments in time, you know, Corina spoke to some of the challenges in brief, but was there a moment in time that you were like, this can never happen...it’s too big.

Barbara Charry: There were a lot of moments in time like that. It was a really big project. And honestly, in talking to lots of people there, you know, a lot of shaking heads of, yeah, this’ll never happen. And so that was actually good going into this with eyes wide open saying, you know, this is really worth doing. It’s worth learning about if we can make this happen, it will be such an incredible opportunity for the community. But we know it’s a big challenge and it may not happen. And so that kept us going with realistic ideas and, and but, but we kept going and kept solving problems and every time we think, okay, we’ve got this figured out. And then there would be something else that we needed to address and learn, because it’s really a learning experience for everybody involved. And we, and we kept solving problems and, and it’s just incredibly excited to have a levee on the ground now protecting that community.

Adam McLane: Wow. Well, this is, I know having seen this project move forward, that there were a tremendous number of partners and what the win like this and success full completion. Do you want to name some of those partners?

Barbara Charry: I sure do. I mean, this is the ultimate partnership project. It was just an incredible effort. And each partner really had a really critical role and I really want to give a shout out to all of them. There was the Northwest Missouri Council of Governments, and they were really incredible on helping in the local level, helping with grant opportunities, environmental and economic assessments. And then there’s the Missouri River Recovery Program. And they were instrumental in providing land and material for building that new levee. The Natural Resources Conservation Service was also critical. They were helping with enrolling landowners in conservation easements. And so this was a way to compensate the landowners for the now riverside land. They have a really important program called the Emergency Watershed Program - Floodplain Easement. And this is disaster funds that come after the 2019 fund that Congress appropriates them and makes them available through NRCS.

Barbara Charry: So that was a really important role. The Department of Natural Resources in Missouri, they were a real problem solver and they helped coordinate all the state agencies that were involved and worked with the Governor as well. And then the Missouri Department of Conservation provided funds for real estate, as well as the State Emergency Management Agency. Again, they were key for providing funding for real estate through appropriations by the legislature that they had made help levee boards and levee districts around the state recover from the 2019 flood. So it was, it was a great effort and each in each of those and all the staff for those different agencies really brought their "A" game. I mean, they were really tremendous problem solvers and team players.

Adam McLane: Wow, there’s a quote, I don’t know who said it, but I I, it always comes to mind in moments like that, which has many hands make light work. And it sounds like that was required for this levee district and I mean, for this levee itself. And then it also sounds like, I mean, there has to be a Venn diagram that had this project sitting right in the middle of that many different missions and future goals for the future. Is that rare, or do you think that that Venn diagram exists elsewhere too?

Barbara Charry: I think it exists elsewhere for sure. And I think, you know, the key role that The Nature Conservancy was able to play because as a nonprofit, we could bring all those different groups together and look at it holistically. You know, each of the agencies have these incredible missions and they provide different components. And, but bringing that Venn overlap part together was kind of our role. And I really do think it could be replicated elsewhere.

Adam McLane: Regan. So what was it like for I’m imagining this moment in time where the, the line gets drawn on a map and the engineering begins and it all makes sense and they start to do a cost analysis, but there’s landowners involved and a community involved, in a new kind of project. What was that like when, when you went back to the community and the levee district started talking to the community and landowners around about this idea?

Regan Griffin: Yeah, I know I was, I was pretty apprehensive. I mean, we, you know, like I mentioned before 2011 had a flood in 93, I had a flood, we had high water events in between those years. And I would just say the general approach has been, always, don’t give an inch, you know, kind of just put back in place. We gave you your, you know, we gave you the levee seventy years ago. You’re good. And you know, I think in general, the thought was maybe if we start giving up, they’re just going to basically want more ground or, you know, we’re, we’re, we’re benefiting you know, nature groups with just giving up stuff, you know, kind of that sense of us versus them, unfortunately, mentality. But you know, really when we went to the landowners and it started talking to them one, I mean, you know, we looked at this just like Barbara saying, I mean, this was one of those opportunities that benefited, you know, groups that maybe wouldn’t normally be on the same side together.

Regan Griffin: But then also, I mean, in looking at it, we, we kind of realized too, this is our best chance for helping some of our landowners in the way they’d been affected by the flood. I mean, they were there’s some ground that was just absolutely devastated. And looking back, even at the 2011 flood, we had landowners, the same thing happened. And again, didn’t try for a setback. I don’t think it would have probably qualified then anyways, the way the, where, where it was broken at. But you know, there’s landowners are still not able to use that ground. You know, it’s still a pile of sand and a lot of places. And so our thought was we’re helping our local landowners, the best we can, we’re helping the, you know, by and large the community and the landowners in the area, because we’re, we’re hoping to give them better resiliency in a flood, hopefully in the future. And then all of the other partners who are coming together, everyone’s kind of getting a part that they get to see something a key part of what they’re trying to advance happen. And so we’re kind of felt like this is, this is a perfect moment to do this.

Adam McLane: So Corina help us fast forward to today and where the project currently is. And, but I do, you do have to go backwards a little bit and talk about the dredging, the sand from the, from the river part of solving a challenge, because that’s just too cool a story not to share. But then after you do that, take us to present day up there, what works still remains.

Corina Zhang: Yes. This project from a construction perspective was just so cool and innovative. I’m going to geek out a little bit here. But yes, but if you think about going back, how do you move 2 million cubic yards of material or approximately 2 million yards of material, you have to find that material from somewhere. And so that includes sand for your seepage berms, which is on the land side of, of the levee cross section. And we realized early on that we don’t have enough sand actually to complete this. And so we were working with everybody. I remember we went into our meeting where there’s like 20 different people. You know, that Barb is leading here and we were thinking, you know, we really need really need sand. And so it was actually one of one of our leads in the field, his name’s TJ Davey. And he said, well, how about we dredge the you know, the sand seepage berms. We had already used this in a different form early on in our previous projects where we closed the breaches using dredging because it wasn’t accessible via land. And so that was the best way to actually close the breaches quickly. And we thought, well, if we could close breaches, maybe we can dredge in place the sand seepage berms. And so that took a lot of coordination with ensuring that we are compliant with environmental regulations. I remember Dru Buntin from, from MDNR making a call to help us like expedite this permit that we needed. Otherwise, we were going to lose our window to dredge. Cause you only have a short window when you can do the, these sort of activities in order not to impact like the from an environmental perspective. And then also from like a transportation perspective, like there’s freights that go up and down the river too. And we actually got it done, like we pulled it off and I remember that dread coming in and we figured out where it would be least impactful to get the sand material and we made so if you think about it, there’s a slurry. So there’s water and sand that is being dredged out and it’s going through this giant kind of vacuum tube, so to speak. And, and then it goes in place where where we put it. And so in order to contain the water, we made these we called it containment berms on either side and made sure that the water went into these ditches that were already existing. And then they go out back into the river and when the water comes out and the sand settles you’re left with fully compacted, sand seepage berms. And so they were, it was phenomenal. It was excellent material and it was so cool to see it happen. You saw my not miles, but a lot of pipelines from the river going into this levee and never been done before. And a lot of people were very skeptical. They thought is this, is this even possible? The entire group, whenever some sort of innovative idea happens. It’s like, why not? Why not try? I love it.

Adam McLane: I was Corina. I, I could have told them it would work because I’ve dripped castles. Right. So I’m going back to my castle. That’s my only engineering that I’ve ever done in my life, probably as clearly and obviously building sand castles by the ocean, but the slurry is really like a drip castle. Right? So you were just vacuuming drip castle material, spraying it on top.

Corina Zhang: That’s it, that’s it you know, some full concept there, kids do it all the time, right?

Adam McLane: Yes. It’ll just be the explanation whenever, whenever you try and do innovative things in the future and you get pushback from other engineers, just turn it into a childhood story about sand castles or something and I’m sure they’ll be like, oh, that makes sense.

Corina Zhang: Absolutely. I’m going to try to live my life as childlike as possible. But yeah, so to continue on with where we’re, where we are. So we so we are pretty close to the end. We actually have, believe it or not, we have a levee in the new alignment. If you look on Google imagery, you’ll see the old levee alignment, and now you see the levee alignment in place. It’s, it’s so cool. We are we’re pretty close to the finish line. So in March was our big push to achieve a full height, levee you know, cross section and then get fully encapsulated by, by mid-March. And we were successful in that, and everybody had a part in it, every agency, everybody on the ground, a lot of the local landowners and the local farmers actually were the operators that help build this levee.

Corina Zhang: So that was huge. They were directly invested in making this happen and we yeah, we’re pretty close. We’re right now just finishing up the sand seepage, berms and placing topsoil, and then we’re going to be seeding and just restoring the ground in between the old and the new levee. So it’s a lot of restoration activities we’re looking to be complete in the summertime this year, which is pretty incredible. If you think about when the flood happened back in 2019 in two years completing it, that’s wild. That’s wild.

Adam McLane: That is incredible. Thanks for sharing that story Corina and you know, I’m just trying to recap, and then maybe I’ll hand it to you Barbara, to let us know the nature side of what the impact will be on the riverside and potentially for nutrients and that stuff. But in recapping, so we had 2019, you know, that, that two year window that you’re talking about 2019, multiple breaches in this section, then deciding in partnership with the community and the levee district, that boy, this is really viable to do this setback, then full construction of that. And when you were talking about operators of the community, helping in these, I mean, that is heavy duty machinery from all around that’s coming and moving dirt and moving dirt and moving dirt. And then now you’re sitting in a spot where it’s been realigned, it’s back. It’s complete on the one side and you’re working on, you know, the other, the non-riverside, just wrapping that side up all within two years. Is that right?

Corina Zhang: That’s a great summary. I also forgot this is a key detail, but I forgot to mention that in between that time, when we were moving dirt the, the Midwest got hit with a polar vortex. I believe most of you all experienced where it was like negative 20 for, for like several days. And then just freezing cold for gosh it was like weeks, I feel like. But I gotta hand it off to the team who continue to be innovative. And they came up with this idea to use these giant tents where you can put thousands of cubic yards - and we had eight tenths that were spread around the site and we pumped them full of heat with heaters. I remember it was, gosh, it was, you know, it was pretty cool, like, you know, in the single digits and you would go on one of these tents, and I remember reading the temperature was like close to 80 degrees in there. So that was the job that people wanted on, when that’s happening, you know, help man the tents. But that really helped us to keep maintaining our momentum because once the cold let up, we were able to continue directly placing, otherwise if we wouldn’t had those, we would have been solved for several weeks. No doubt. But, but yeah.

Adam McLane: Well, and I saw those tents on that visit. And so listeners, if you were to think about like your little gazebo tent that you use at sporting events or whatever, they’d have the little frame that goes up on the side, multiply that times like 3 million. And that’s probably the size of it. It was like two football fields would fit inside. There was a football field. What was it, Corina? Was it a football field would fit inside each one of those tents? And you had like 10 of them.

Corina Zhang: I want to say it was, I can’t remember the actual amount, but you can fit a giant excavator in there and dozers. And, and so you can think about moving that. I think it was approximately two or three football fields, something like that.

Adam McLane: Okay. Barbara we’ve talked infrastructure on the site and the design of the levee itself. But there, but we’re also talking about digging soils out and replacing them and then having, what a thousand new acres inside that are now connected to the levee or connected to the river is that accurate?

Barbara Charry: That’s right. That’s right. So doing this levee setback, we’re ending up reconnecting over a thousand acres of land that was landward of the old levee - it’s now river word of the new levee and reconnected to the river. So this has incredible environmental benefits and it’s been seen in other places where, where land’s been reconnected to the rivers and restored just an incredible amount of habitat. I mean, floodplain habitat is incredibly rich. It is just high value for lots of animals. One of the things that happens is the fish species really do great in there. They spawn, its nurseries. And so that in turn provides a ton of food for birds and mammals. And so it’s just an incredible place for, for nesting animals and feeding and migrating animals. And so this area is actually, it’s actually where the Mississippi and the central flyway come together up on the Missouri river in that area. And so you’ve got a tremendous amount of waterfowl that are migrating through and they are hungry. They need, they need a lot of energy to make it up and down on their trips. So we’ve seen, you know, in these places that there’s a lot of response and a lot of use, and when the levee’s restored all that land and they’re excavating and building, they’re creating these small depressions that are mimicking and become wetlands, right. Where, where all that food and, and feeding can happen. So that’s part of the construction process is recreating those wetlands and then allowing things to sort of naturally vegetate and restore that way. And we know on the Missouri River because it’s levee there, there’s not a lot of these floodplain pools. And so they’re really important places for wildlife or migrating along the Missouri River. So this is really creating a lot more of that habitat. And then also water quality. That’s another, you know, another really key benefit for nature and for people to actually. That story you’re talking about the the seepage berms for the dredged material. You know, it’s the same thing when, when the waters come into a floodplain, all the water slows down and all that sediment and material that’s in the water settles out just as, as you use to create the new levee that’s happening in the floodplain. And so those sediments, which are have a lot of nutrients in them, they settle out, out on floodplains and help clean the water. So it’s, you know, contributing to a cleaner water, which is, which is another great benefit of this project.

Adam McLane: Wow. Regan, can you tell me your favorite place to eat breakfast in Rock Port without getting in trouble with other people that have breakfast places up there?

Regan Griffin: (laughs) Unfortunately, there’s, there’s a few places that opened it up. I haven’t tried, there’s a new place called the Bowling Alley, I need to try out. But unfortunately we had a lot of restaurants closed because of the flood at least kind of two. And so unfortunately it was one of them that I like, so I need to try out the Bowling Alley otherwise it’s, McDonald’s usually, which wouldn’t really call a good breakfast place. I’m not going to call it that.

Adam McLane: Okay. Well you go to this breakfast place, whichever one, it happens to be whether it’s McDonald’s or the Bowling Alley is that you said I was gone. Yep. Okay. Okay. So you go sit at the Bowling Alley for breakfast and have a cup of coffee, and there’s a lot of other people sitting around having a cup of coffee, and they’re talking about this project and how it all happened and whether they feel good about it or whether there’s still anxiety or what does that coffee talk sound like right now in a community the size of Rock Port?

Regan Griffin: I mean, I think the big thing is just the hope for, we’re not going to be doing this again in five or 10 years. And I mean, you know, there’s a lot of issues, climate change, whatever that might be causing this to happen more regularly. But our hope was in doing this project, that we were not going to be fighting the same fight over and over, which we’ve been fighting now for years. But that, you know, this section of levee, at least we’re not going to have to say, okay we had another catastrophic fail there, the next flood. But, you know, potentially it moved back and we don’t even have flooding there. Or if we do, you know, that this new levee, the design of it, the way it was built, that it’s going to stand up. And so our hope is that the landowners down there feel, Hey, we’re secure for, you know, these, these events stand for 67 years. We’re, we’re good for another 67 plus years you know, be protected.

Adam McLane: What would you tell other levee boards or communities that you know, look to this as a, hmm. Is this something that we should consider? What would you tell those groups or how to go about even starting thinking about a process like this?

Regan Griffin: I mean, you know, it’s kinda like, I was just saying, I think the big thing was, we just, we said we’ve got to do different you know, we don’t, and I’m sure a lot of communities feel like this who’ve experienced floods or flooding, you know, 2019, maybe 2011, maybe 93, similar rests or, or other kind of moments like that, that, you know, you can keep fighting that same area, keep, you know, hey, we’re going to figure out how to put this right back together, where it is. And then, you know, the next flood potentially have to deal with that same spot. Or you can say, hey, let’s use the opportunity to look at other options for solving this situation. And, and that’s what we did thankfully we had you know, the rest of the board was on board for that. Thankfully the community members, the landowners specifically, but other folks that we were working with were behind it. And I mean, I’d say the biggest thing, you know, you asked Barb, you ask Corina, I mean, we, we, this would not have happened without the partners involved and we’re so thankful for TNC and all the work that they did, the Corps as well, and worked with some great folks, Corina and others at the Corps. But yeah, I mean, even felt very supported and backed by our Governor, Governor Parson and Dru Buntin, the DNR, and so many different agencies saying, hey, we want to help make this happen because I mean, this is a lot of money, the real estate piece, and, you know, putting all together, it was, it was a lot of money that a levee district like ours just doesn’t have the money to do that. But thankfully we had, you know, bigger groups and bigger agencies who were willing to say, hey, if you guys are actually willing to do this, we’re willing to come alongside you. I mean, that’s a big piece is just, you know, it’s, it’s not, it doesn’t have to be owned by your local community. I think if you start reaching out, I think there’s groups that will help make this happen. If you start asking the right people and getting there.

Adam McLane: I love it. And since Regan started talking about hopes for the project and for it lasting a long time and hopes within the community, I’ll ask Corina and Barbara both about what are your hopes from this project? So Barbara, you want to go first and then I’ll hand it over to Corina.

Barbara Charry: Sure. So, you know, I really, I really hope that this, this project inspires people to find solutions for their community that really improve their lives, improve habitat, benefit, nature and that they reach out to develop partnerships. And that when things are difficult, it doesn’t mean they’re impossible. There’s always way to get things done. You know, just what Regan was saying, you know, with community leadership and reaching out you know, really that’s, that’s the most important ingredient is that community leadership,

Adam McLane: Great, Corina? What are you, what are your hopes for this project moving forward or what, what was learned from this project or what is learned from the project? Tell me about your hopes.

Corina Zhang: Man. Craig question. I really want to echo what Bard said. And my hope when people look at this project is they see it and say, we can overcome big obstacles to that. There’s nothing too big that can’t be overcome and, and, and to bring people with them like you really need, you need everybody, you can’t, there was no way this project could have been done just with one entity. There’s, there’s no way and big problems that, that a lot of people face that a lot of different agencies will face you, you need everybody. And that you’re on the same team that I, yeah, my hope is that when people look at this, they see that even though all of these different agencies had different priorities or different resources, we were all on the same team and that we all wanted each other to win just as much as we want to have our priority met too. But yeah, you, you need each other, we all need each other.

Adam McLane: Last words that anybody wants to share with, or talk to about the partnership or anything else about this project before we kind of wrap up this story.

Barbara Charry: You know, I just wanna, I just wanna thank everybody. You know, I want to thank everybody for coming together for the partners, for being honest and, and digging deep for solutions being willing to take chances and going above and beyond, you know, it was a big lift for everybody involved and I really want to thank them for seeing what was possible. And, and again, the success of the project was really due to each agency and each person and Corina and Regan and, you know, all, all the others. So thank you.

Regan Griffin: I would just say kind of, I mean, even Barbara was mentioning earlier about the hope piece. I know one of the things we were even helpful to help, you know, be a pilot program, I guess you would say again, helping communities realize you don’t have to keep doing the same thing over and over there’s opportunities to kind of change and help set yourself to be more resilient. And so that was even one of our things going into this is realizing, I mean, this, this doesn’t happen normally. And there’s a reason why all this, all the hoops you had to jump through you, it was pretty difficult. So hopefully the next time someone decides, hey, I’d like to maybe look at doing one of these, that the blueprints there, we know how to do it now. And you know, you know, you guys at TNC or other agencies can step in and say, hey, it’s, it’s not reinventing the wheel. We can do this.

Corina Zhang: oh man, they all, everything that you guys said. I also do just want to thank everybody who’s listening right now, who took the time and wanted to listen. And then and the, the leadership of all of the different agencies, they helped support us whenever we would make decisions. You know, they, they really supported us and were behind us. And I think you know, good leadership, sometimes it’s hard to come by. And the leadership of all of these different agencies were very instrumental. And so they all know who they are and we all appreciate them.

Adam McLane: Well, I am going to share something Corina with Corina and Barbara. That’s kind of personal. I have an 11-year-old daughter named Morgan who loves to build stuff and is like, she’s strong-willed. And so seeing you too, in your leadership positions within this project, just like rocking out a levee and figuring out new problems and how to move them forward is like an incredible role model, like to look up to. And, and cause she thinks about, you know, out in the world, what is it that I can, and can’t do? What are my skillsets gonna allow me to do? And seeing people like you leading these kinds of projects is really, really cool. So thank you for that leadership and for rocking this kind of stuff out for future generations to look at and go, yeah, I can do that. I can build levees. Heck yeah.

Regan Griffin: I’d like to get some quality women working here.

Adam McLane: Agreed. Well, thank you all very, very much. I know zoom is difficult to do these things onto and so you taking the time to share this story, I think is really remarkable. I want to share all my gratitude for the partnership that created this project. And I share all of these hopes that you all share in particular that it works and it works for a long, long, long, long time. Because I think that’s a pathway forward to seeing more and more of these happen in the right places throughout that system. And I want to thank everybody that listened today.

And if you have, if you have a desire to dig a little bit deeper into this project, pun not intended, but it’s pretty good. One for more information on the project, go to nature.org/moriverlevee—that levee with two E’s. And for more info about The Nature Conservancy and what we do, you can visit, visit nature.org/missouri. So thanks for listening and be sure to subscribe to our podcast so you can catch future episodes.

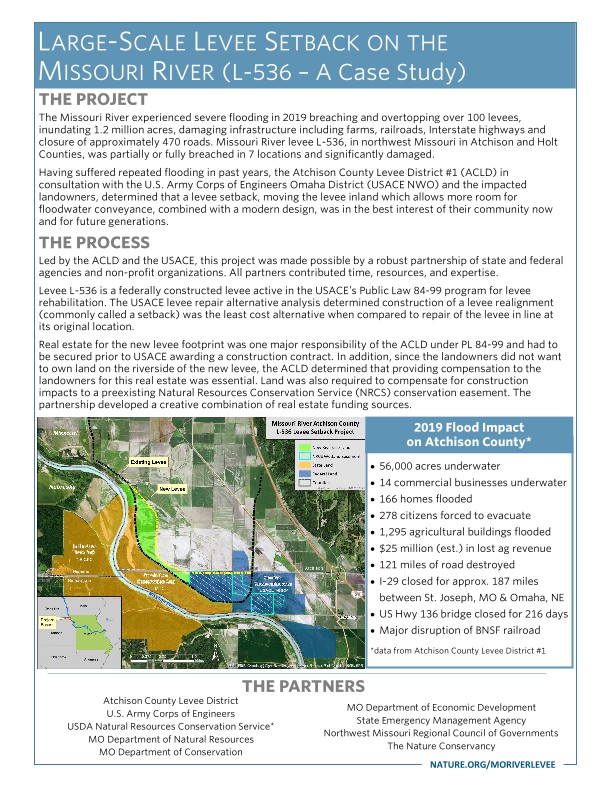

2019 Flood Impacts to Atchison County:

- 56,000 acres underwater

- 14 commercial businesses underwater

- 166 homes flooded

- 278 citizens forced to evacuate

- 1,295 agricultural buildings flooded

- $25 million (est.) in lost ag revenue

- 121 miles of road destroyed

- I-29 closed for approx. 187 miles between St. Joseph, Mo & Omaha, Ne.

- US Hwy 136 bridge closed for 216 days

- Major disruption of BNSF railroad

Devastating Impacts on the Community and the Agriculture Industry

The extreme flooding that the northwestern side of the state experienced in the spring of 2019 was devastating to the local communities, businesses and the agriculture industry.

The Missouri River breached over 100 levees, inundating 1.2 million acres, damaging infrastructure including farms, railroads, Interstate highways and closing approximately 470 roads. Missouri River levee L-536, in Atchison and Holt Counties, was breached in 7 locations alone—and suffered significant damages.

At the time of the flood, the current levee, which was originally constructed in the 1950s, and could be at risk for future breaches if reconstructed in the same alignment.

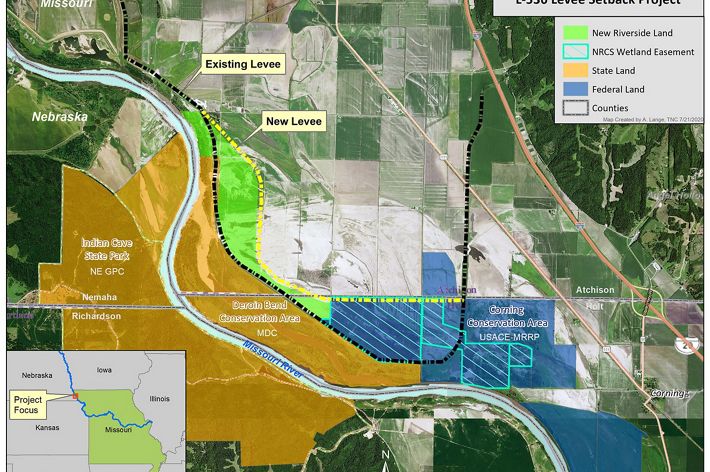

The Atchison County Levee District in consultation with the impacted landowners, determined that a levee setback—moving the levee inland to allow more room for floodwater—combined with a modern design, was in the best interest of their community now and for future generations.

Finding a Longterm Solution to Lessen Flood Impacts

As president of the Atchison County Levee District (ACLD) in Missouri, Ryan and his board are responsible for one of the largest levee districts in the country, maintaining 54 miles of levee along the Missouri River.

The group now had to develop a workable plan to minimize flood damage and address environmental concerns.

After discussions with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), it was determined that a levee setback—moving the levee to allow the river more room—was possible. The setback was the best long-term solution, but it wasn’t the easiest option.

“We were going to these landowners, many of whom are farming land that’s been in their families for hundreds of years, and telling them we are thinking about a setback, and that their ground would now be outside of the levee,” he said. “It’s not an easy ask.”

Project Partners—Resource Links

- Atchison County Levee District

- Missouri Department of Conservation

- Missouri Department of Natural Resources

- Northwest Missouri Regional Council of Governments

- State Emergency Management Agency

- The Nature Conservancy

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—Missouri River Recovery Program

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—Omaha District

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

Bringing the Partners to the Table

The young ACLD board recruited help from a host of partners—including The Nature Conservancy—and support from previous generations within its community to partner with the landowners and get the project done.

TNC’s Barbara Charry was brought into the conversation.

“One of the things that TNC can do as a nonprofit is to convene people and so that's what we did,” says Barbara. “We brought together our partners from across the state with the levee district and the USACE to set up a partner meeting in St. Joseph, Missouri in August of 2019.”

The groups identified a lot of barriers and problems and yet there was a lot of excitement and interest in making something happen. “All partners played a critical role in a variety of ways to figure out a problem, find a funding source, find a technical solution, find a political solution and move things forward,” she says.

Demonstrating the Benefits for Landowners Up and Down the River

“Max Peeler is a crucial part of this levee system, and he has been for years,” says Ryan. “He has lived and breathed the Missouri River and levee system all his life. He’s a very valuable source of information for us and he’s also a landowner and a farmer in the section where we needed a setback.”

Max agreed with the plan but said it’s always hard to give up land. “You hate to give up land, but when we started looking at the wetlands it seemed like the right thing to do,” says Max. Soon after, all the other landowners were on board, as well.

Quote: Ryan Ottmann

We want this to be a pilot project, to show other communities that it’s possible.

Ecological Benefits of a Levee Setback

- Floodplain habitat for fish and wildlife

- Spawning and nursery areas for many fish species during high water

- Fish and aquatic life in the floodplain during highwater are food for birds and mammals

- Increased groundwater recharge

- Floodplains improve water quality by retaining nutrients deposited during floods

The setback benefits the local community, those downstream and the whole ecosystem that surrounds it. “It’s about preserving nature and coexisting with it. We both benefit when it’s done correctly,” says Ryan.

“We want this to be a pilot project, to show other communities that it’s possible, and set a precedent so it will be easier in the future,” he says.

“This is an incredible demonstration project that other landowners and levee districts up and down the Missouri River can look to as one of the tools in the toolbox to help with the catastrophic flooding that we’re all facing right now on the Missouri River,” says Barbara.

This project is teaching the complexity of this type of system and the pathway forward. “Our intention is to take the information here and work with all of our partners to improve those programs so that it becomes easier for other levee districts to make this choice in the future,” she says.

Looking Toward the Future

New levee construction began in August 2020 and was completed by the summer of 2021. “We couldn’t have done it without the help from our community, our partners and from TNC,” Ryan says.

For Barbara, the project brings a lot of optimism about the future. “There are so many people out there working away in different agencies, and landowners who are willing to take a chance and do something different,” she says. “It gives me a lot of hope for the future.”

Ryan agrees and for him, this is more than just a levee project. “We just had twins, a boy and a girl, and we named our son River James. So yeah, this river means everything to me,” he says.

Inspiring Change

“Don’t think you can’t do it.” That’s Ryan’s advice for other levee districts and landowners who are in a similar situation with repetitive flooding. “There are funding mechanisms to get this done. They’re not easy but we also hope to help that become easier,” he says.

The group of partners continues to collaborate on this project with a goal to lessen the challenges that can make a project like this seem impossible.

The playbook and factsheet below include some of the technical aspects of the project along with contacts and representatives from partners who can provide additional information for interested levee districts, landowners and communities.

Any communities or organizations that are interested in learning more about this project are encouraged to review the factsheet and contact one of the partners for more information.

Get the Levee Setback Playbook

Learn from the experiences and read recommendations from the L-536 project partners.

Access the PlaybookDeveloping a Playbook

Following the historic flood, and construction of the levee setback the partner group took their lessons learned and collaborated on the L-536 Levee Setback Playbook—a how-to guide for communities interested in pursuing similar nature-based solutions that enhance flood resiliency.

“The L-536 levee project in itself is a great demonstration for how communities can use nature-based approaches to reduce their flood risk,” says The Nature Conservancy’s Barbara Charry. “This playbook is our way to help make it easier for communities to pursue those approaches.”

The development of the playbook was supported by The Nature Conservancy with experience-based contributions from project partners involved in the L-536 realignment project including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

Quote: Dru Buntin

I believe this playbook can be a great resource to our river communities in Missouri and beyond.

“In my opinion, building a project this complex as fast as we did can’t be done by the USACE and a levee sponsor alone, you need a team of focused collaborators,” says Dave Crane, Environmental-Lead on L-536 for the USACE. “Our experiences, expertise and recommendations can be used to help communities and decision-makers evaluate habitat-and-flood risk management win-wins through the power of partnership, whether it’s for pre-disaster planning or recovery after a severe event like what happened in 2019.”

Dru Buntin, Director of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources says one of the key takeaways illustrated in the playbook is the power of local leadership demonstrated by the Atchison County Levee District, which took a holistic approach with their entire levee system. “I believe this playbook can be a great resource to our river communities in Missouri and beyond that have dealt with repetitive flood events and want to look at more resilient and protective solutions,” says Buntin.

Print-Friendly Version of the Playbook and Sections

- Complete Playbook (.pdf)

- Executive Summary (.pdf)

- Section 1 (.pdf)

- Section 2 (.pdf)

- Section 3 (.pdf)

- Section 4 (.pdf)

Interactive Playbook Sections

The interactive playbook can be viewed in its entirety or by section:

- Executive Summary

- Section 1: The Story—tells the story of the historic flooding in 2019 and provides an overview of the scope and benefits of the setback, the partners involved and project milestones.

- Section 2: The Challenges—dives deeper into the L-536 setback project, identifying the challenges—big and small—that project partners encountered and overcame through collaborative problem solving.

- Section 3: The Recommendations—provides recommendations from the lessons learned during the L-536 setback regarding legislation, regulation, policies and practices that can better support levee setback projects.

- Section 4: The How-To Guide—illustrates a process for levee sponsors considering or pursuing a similar project, as well as identifying helpful pre-disaster planning efforts.

Completed Environmental Assessment

The USACE completed a tiered Environmental Assessment for the L-536 project to document the alternatives analysis, compliance with environmental laws and overall results of the levee setback project. The final report and appendices can be found here.

Download

Learn more about the levee setback project including technical details and environmental benefits.

DownloadMake a Difference in Missouri

Since 1956, we have worked to conserve the lands and waters that make Missouri unique and beautiful. Your support has helped us protect more than 150,000 acres, and we’ve still got a lot of work to do. Your donation will make a difference. We can't save nature without you.