Ocean and Coasts Network

The Ocean and Coasts Network will help us tackle challenges across a vast geography of shorelines and open waters in the southeastern U.S. and Gulf Coast region.

This endangered baleen whale is threatened by boat strikes, fishing gear entanglement and climate change—but The Nature Conservancy is here to help.

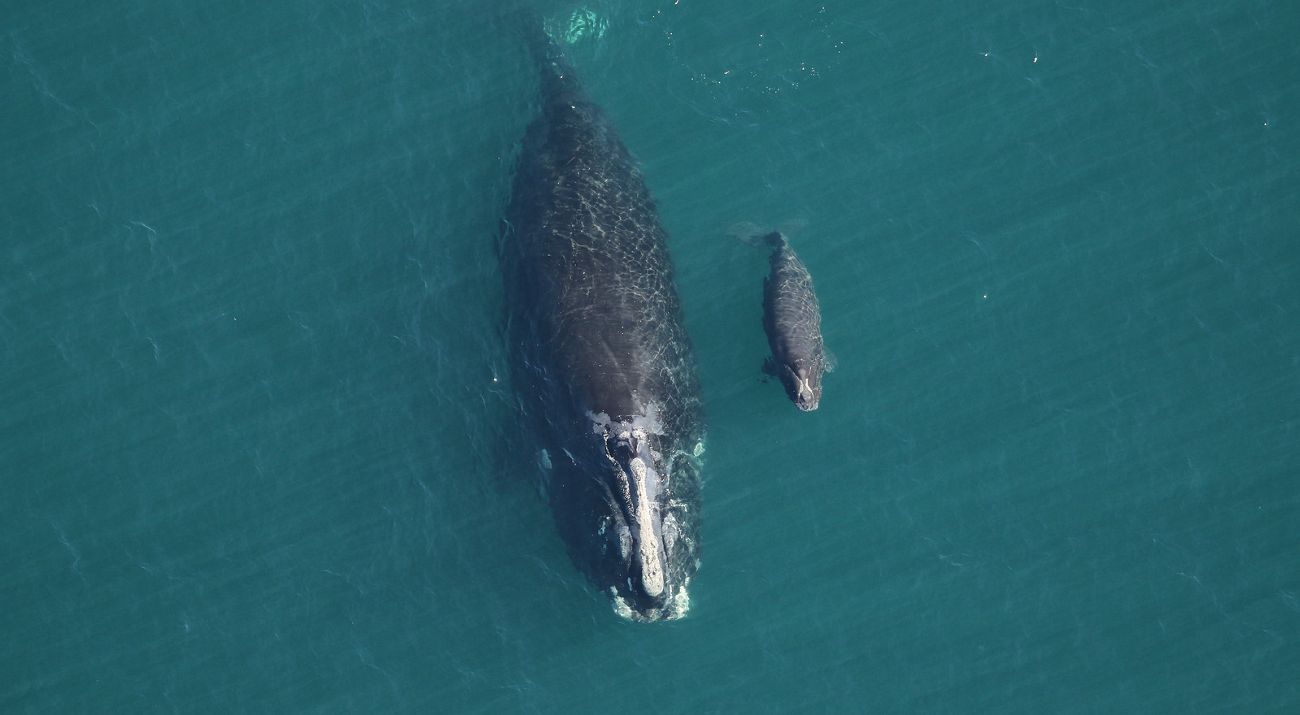

The aerial image captured off the coast of Georgia should have been a heart-warming sight: a North Atlantic right whale, flanked by her calf.

On closer inspection, however, it was clear that the mother, Snow Cone or #3560, was entangled in fishing rope.

“Our colleagues in New England and Canada cut more than 100 yards of rope off of her last year, but they weren’t able to remove it entirely," explains Clay George, senior wildlife biologist at Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

"The fact that she was still able to migrate south 1,000 miles and calve successfully is a minor miracle.”

North Atlantic right whale #3560, known as Snow Cone, swims with her calf. Snow Cone shows obvious signs of entanglement 10 nautical miles off the coast of Cumberland Island.

The North Atlantic right whale, which can reach up to 52 feet in length, is one of the most endangered whales in the world. Its tendency to hug the coastline and travel near the water’s surface at slow speeds, combined with its docile nature, made it an attractive prospect to 19th-century whalers. They all but killed off the species, leaving an estimated population of only 100 by the turn of the 20th century.

Although the species increased slowly but steadily after whaling was ended, the population has faced a sharp decline over the past 10 years, from 480 whales in 2011 to approximately 375 in 2022. That’s a 20% decrease.

As of 2025, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates only about 370 individuals remain, including about 70 reproductively active females.

A North Atlantic right whale has fishing gear trapped in its jaws. Rope can be seen stretching along its body and past its tail.

Humans remain the greatest threat to this beautiful and peaceful creature, with boat strikes and fixed fishing gear accounting for almost all non-calf deaths and serious injuries. Another human impact, climate change, has exacerbated the danger.

“Historically, most of the whales spent the summer months feeding in the Gulf of Maine, along the U.S./Canadian border, but warming waters caused by climate change are pushing them farther north to the Gulf of St. Lawrence,” said Clay George, senior wildlife biologist at Georgia Department of Natural Resources. “This is a serious problem because there’s more vessel traffic and fixed fishing gear, like lobster and snow crab.”

The whales get little reprieve when they travel south to the coast of the Carolinas, Georgia and North Florida to calve. Two calves and one mother whale have been struck by boats off Georgia and Florida in the last five years. And ship traffic from busy East Coast ports poses a serious risk during the whales’ southward and northward migrations.

The good news is that the North Atlantic right whale has proven to us in the past that it can bounce back and recover, if we give it the opportunity.

The Nature Conservancy is one of many partners working toward the whales’ recovery. One key piece of the puzzle is better data.

TNC scientists have focused on mapping areas of the Atlantic vital to the right whale’s migration patterns and feeding and calving grounds.

“These tools build on decades of research and can help us better understand where critical habitats are located and their relationship with right whales and other key species,” says Mary Conley, Southeast marine conservation director for TNC.

“It also shows us why it’s so important to work across state and regional boundaries—we can’t take a state-by-state approach to helping species that travel thousands of miles in their lifetimes.”

The South Atlantic Bight Marine Assessment, launched by TNC in 2017, for the first time collected map layers illustrating water depth, migration routes and sea floor features from North Carolina to the Florida Keys. A new Southeast Marine Mapping Tool, introduced in 2025, arms scientists and policymakers with an easier way to parse through that data.

Why is this data so important? Because data informs ocean planning decisions. For example, a better understanding of whale migratory routes and calving grounds was behind NOAA’s establishment in 2021 of Right Whale Slow Zones. This voluntary program notifies vessel operators when they’re entering territory in which whales have been spotted, encouraging them to slow down to avoid collisions. In 2023, with funding from the Inflation Reduction Act, NOAA announced a partnership with the federally funded Center for Enterprise Modernization to further improve data on how to detect whales and avoid ship strikes in high traffic areas.

“The good news is that the North Atlantic right whale has proven to us in the past that it can bounce back and recover, if we give it the opportunity,” says George.

Solutions for Sustainable Fisheries

The Nature Conservancy has designed tools to improve long-term sustainability of marine resources. We've also joined forces with crab fishermen to keeps whales and other marine life safe.

Sign up to receive email updates from TNC in Georgia

Cashew is seen “cradling” her calf, a common mother-calf behavior in which the mother is belly up and the calf rests on or above her belly between her flippers.