Six Black Conservationists and Environmental Activists to Celebrate

Black leaders have been advancing conservation for centuries. Here are just a few of their stories.

Conservation at its best embraces all voices—globally and in the United States.

Black leaders have been blazing a path in conservation for centuries.

Our best chance to solve our planet’s most complex problems relies on the strength in our differences and brings together all of our ideas.

We hope you find inspiration in this group of Black conservationists who have led—and continue to lead—the way forward. While we may never know the names of all Black environmental stewards and activists who have shaped the American landscape, their contributions live on.

Carver used his talents as a scientist, professor, farmer and inventor to regenerate soil and build economic self-reliance for former enslaved people kept in debt by sharecropping.

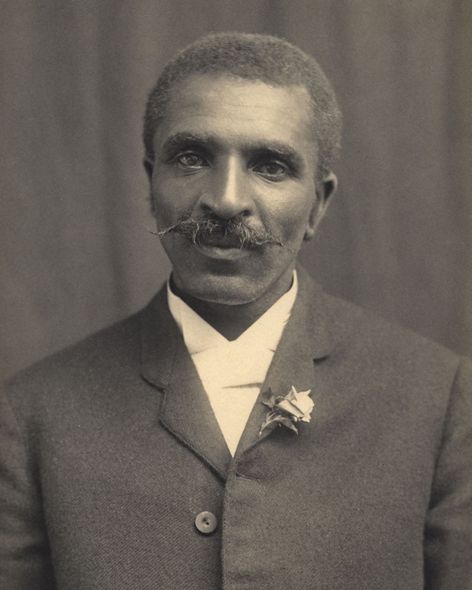

George Washington Carver

One of the most impactful conservationists in United States history, George Washington Carver healed land and uplifted farmers recently freed from slavery.

Born into slavery himself, Carver overcame race-based rejections from multiple colleges and became the first Black student at Iowa State University and later its first Black faculty member.

He helped found the agricultural school at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute. Upon arriving in the South, Carver noted how degraded the soil was from a long history of intensive cotton growing.

Carver experimented and perfected ways to bring nutrients back to the land: an idea that in modern times is embraced as regenerative agriculture, a powerful climate solution.

Carver’s methods of rotating a variety of crops and turning some cover crops under the soil boosted the land’s productivity. To create a market for diverse soil-fixing crops like peanuts and sweet potatoes, Carver invented hundreds of uses for them.

By demonstrating these lessons far and wide, Carver hoped to liberate the region’s formerly enslaved Black farmers from a sharecropping system that kept them indebted and dependent on white landowners.

While his historical narrative is often tied to his promotion of the peanut, his tireless efforts to take on an unjust status quo through nature and ingenuity are now seeing the light of day.

Due to his contributions to the nation’s agriculture, Carver was the first non-president to be honored with a national monument.

Hattie Carthan

Hattie Carthan had been interested in trees all her life, but it was her love for her home and her neighbors that sprung her to action. When her once tree-lined neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn started losing its trees at an alarming rate, she started replanting them herself.

At the age of 71, Hattie founded the Neighborhood Tree Corps to inspire young people to care for and plant trees. Her passion helped build a grassroots movement for more green space in cities.

Carthan’s acts of community engagement and environmental action live on through the Hattie Carthan Garden and the Magnolia Tree Earth Center.

Rue Mapp

As a child exploring her family’s ranch, Rue Mapp realized that we’re not separate from nature and that nature is best shared with others.

In 2009, Mapp started a blog called Outdoor Afro to reconnect more Black people to the outdoors. Since then, it’s turned into a non-profit organization with more than 100 leaders in more than 60 cities across the US.

Today, Outdoor Afro provides leadership training and community building, dispels myths about Black people and the outdoors, and generates enthusiasm for nature. Leaders organize trips from mountain climbing to kayaking to exploring city parks, where participants practice conservation stewardship, including environmental ethics and education.

For more than a decade, Mapp has been changing the visual narrative of people in nature and helping create a future where nature and people of all communities thrive together.

Get more nature stories in your inbox

Hazel Johnson

Known as the mother of the environmental justice movement, Hazel Johnson fought to improve living conditions in Chicago public housing from the 1970s until her death in 2011.

She began investigating high cancer rates in her neighborhood of Altgeld Gardens and discovered the problem was environmental. Altgeld Gardens was built on a landfill, and the air, water and land around it was polluted.

Johnson went on to found the People for Community Recovery and was committed to environmental change. A hallmark of her activism involved working with activists to collaborate with the Environmental Protection Agency and urge President Clinton to sign the Environmental Justice Executive Order.

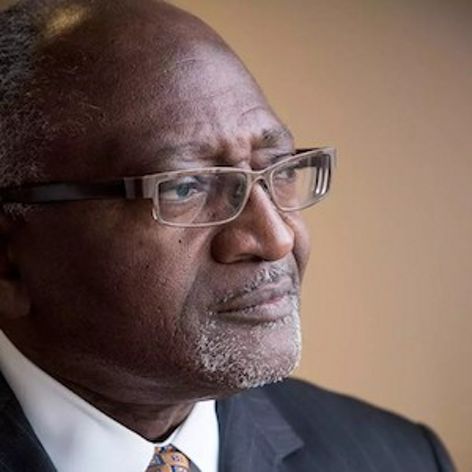

Dr. Robert Bullard

Robert Bullard is known as the father of environmental justice, a movement to promote a more equitable manner for how different communities experience environmental benefits and burdens.

Bullard's efforts began with Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Inc. (1979), a case in which an African American community in Houston rallied against the establishment of a landfill in their neighborhood. In his research, Bullard found toxic waste sites were often placed within Black communities in Houston.

He’s since gone on to become an honored activist, author and mentor in environmental justice. In 2020, he received the Champions of the Earth Lifetime Achievement Award, the highest environmental honor granted by the United Nations.

He is currently a distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University.

Colonel Charles Young

Born to enslaved parents in 1864, Charles Young was the first Black colonel in the US Army and the first Black superintendent of a national park, among many other accomplishments.

At a time when the military supervised all national park activities, Young was sent to Sequoia and General Grant National Parks (now Sequoia and Kings Canyon). His troops built roads that opened up the giant sequoia groves to tourism for the first time, an accomplishment previous superintendents had been unable to complete. Parts of these roads are still in use today.

Another lasting legacy was his recommendation that the government acquire more land surrounding the parks and his early negotiations with landowners to sell.

In his report to the Secretary of the Interior, he wrote:

“A journey through this park and the Sierra Forest Reserve to the Mount Whitney country will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are, with their clothing of trees, shrubs, rocks, and vines, and of their importance to the valleys below as reservoirs for storage of water for agricultural and domestic purposes. In this, lies the necessity of forest preservation.”

History continues to be made

The number of Black Americans who have broken barriers to contribute to conservation is far greater than this list. There are unsung heroes and lesser-known leaders in communities all across the nation who are working to create a future where all people and nature thrive.

Follow these organizations and others in your area to stay plugged into conservation work from a diversity of voices.