Report: Mesquite Bosque Habitat Can Be Effectively Restored

Protecting nature starts with science.

In 2025,

TNC released Becoming Bosque: Testing the benefits of mesquite restoration, a report that details learnings from restoration efforts at TNC’s Middle San Pedro River Preserve.

Gnarly mesquite trees grow in valleys across the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. They are common and can even be a thorny nuisance in some situations.

It might seem curious, then, that The Nature Conservancy is working to better understand how to restore mesquite trees. But as the saying goes, location is everything—and in the desert, that means proximity to water. On dry slopes, they become scattered shrubs. But near rivers, they can grow into tall trees and form woodlands called mesquite bosque.

“Mesquite trees are the anchor species of mesquite bosque, an incredibly important and relatively rare habitat type,” says Gita Bodner, Ph.D., conservation ecologist with TNC in Arizona. Mesquite bosques are ribbons of forests that tend to grow alongside rivers, just outside the line of the most water-loving trees like cottonwoods. The land underneath these riparian forests is generally flat; their roots reach to shallow groundwater, and fertile soil builds over time. “Over the past 200 years, large areas of bosque have been cut down or dried up,” says Bodner. “We're just now learning how to get some back.”

What Is Riparian?

Riparian refers to the bank and land closest to rivers and streams. This zone is where trees and plants that need the most water thrive, and they are generally resilient to flooding.

Bodner has authored Becoming Bosque: Testing the benefits of mesquite restoration, a report that details learnings from restoration efforts at TNC’s Middle San Pedro River Preserve. “This research indicates that in areas with appropriate growing conditions, habitat that resembles mesquite bosque form and function can be restored in 20 years or less.”

Leveraging Our Lands

According to Bodner, identifying potential restoration sites is challenging, and there is little research on how to establish new mesquite bosques. “It’s more than the trees,” says Bodner. “It is the soil, the mix of plants, the climatic conditions. Most of all, it’s access to water; those shallow groundwater areas, where the top of the aquifer sits within reach of tree roots.”

Arizona’s Apache Highlands region, which includes the San Pedro River, is a prime area for mesquite bosques. In 2002, TNC acquired 1,900 acres in Cochise County that has become the Middle San Pedro River Preserve, where velvet mesquites grow in both mature bosque woodlands on shady terraces near the river and in upland scrub stands on dry hillsides. There are also areas of floodplain terrace previously cleared for farming. TNC halted crop irrigation on the preserve to leave more water for the river and allowed native plants to recolonize. Young mesquite trees in second-growth riparian thickets quickly appeared and now cover most of the once-farmed fields.

Science in Action

Since 2021, TNC and partners have been studying mesquites on the preserve to better understand differences across landscape settings, tree ages and management choices.

“We set out to evaluate if second-growth thickets are becoming bosques,” says Bodner. “Do they function more like their rare mature forest neighbors, or like the common upland scrub?”

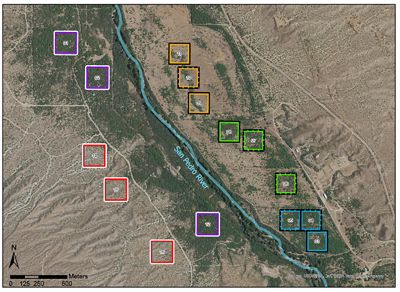

Researchers divided the Middle San Pedro Preserve's mesquite-dominated habitats into 15 six-acre plots to compare values across three main stand types—mature mesquite bosques, second-growth thickets and upland scrub.

- Mature sections of the preserve on the west side of the river include some of the best bosque habitat in the region. Plots in this tall forest habitat were used to understand “reference conditions” to evaluate how similar other areas are to bosque form and function and to establish desired condition targets for restoration prescriptions.

- The hills above are clothed in desert scrub habitat, with a combination of scattered mesquites and other shrubs; plots in this habitat provide a contrast that shows how different bosques are from the upland mesquite habitats that are much more widespread in the region.

- On historic floodplain to the east, the preserve’s 300-acre farm field was fallowed in 2002 and now features second-growth mesquite that range from dense thickets to strands of woodland winding through open terrain.

As an additional part of the research, trees were selectively thinned from some of the second-growth thicket plots, to test whether that tactic could accelerate recovery to the form and function of nearby mature stands.

The results, available in a comprehensive report, indicate that with the right growing conditions, functioning mesquite bosques can be restored in a practical time frame. “It’s surprising how fast these trees are growing and how much wildlife the thickets already support,” says Bodner.

Connecting the Results to Biodiversity

Scientists and land stewards have long known that mesquite bosques provide benefits such as shade, floodplain protection and carbon capture. The research at TNC’s Middle San Pedro River Preserve suggests that near-stream areas of second-growth mesquite thickets may be providing more wildlife benefits than is commonly recognized.

Researchers including Aaron Flesch, Ph.D. with the University of Arizona helped document breeding bird communities in the study plots. “Mesquite bosques are among the most significant and biodiverse environments in our region, but they face major threats,” said Flesch, who designed the bird survey found in the report. “Restoring these subtropical woodlands is important for wildlife, and this work offers major opportunities to further that goal. Birds are ideal monitoring tools for this purpose given their dependencies on a diversity of resources and conditions in these systems.”

To understand how stand structures affect bird populations, researchers used point counts and spot mapping to estimate bird abundance and species composition from visual and auditory observations three times per year in the breeding seasons from 2021-2024.

- Lucy’s warblers, often considered mesquite bosque specialists, also nested frequently in second-growth thickets. Mature bosque stands still had denser populations—up to 7 pairs per acre. This suggests that second-growth riparian mesquite stands may be important for Lucy’s warblers across the region and that this habitat value can continue to improve as young thickets mature.

- Yellow warblers and yellow-breasted chats are also common in riparian stands but avoid upland scrub. These birds nest even more often in thickets than in mature bosque stands, which suggests that bird diversity may benefit from having a mix of tree ages within mesquite bosque zones.

- In contrast, black-throated sparrows, a hallmark bird of deserts, were abundant in upland scrub plots. Apart from small numbers in the sparsest of thicket plots, they are almost entirely absent from bosque and thicket sites. Western kingbirds and verdins also preferred upland stands. These birds underscore the differences between upland and riparian mesquite habitats.

The Sounds of Mesquite Bosque

Lucy's warbler by Dave Slager; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Natural calls and songs from a Lucy's warbler.

Up to 80% of Arizona wildlife species are dependent on riparian areas for breeding, migration, shelter and seasonal forage during some part of their life cycles. “Shady woodlands of tall mesquite trees are a primary reason why the San Pedro is a major flyway for migratory birds,” says Bodner, “and healthy mesquite bosques provide resident birds with flowers to sip, bugs to eat and places to rest, nest and raise their young.” The report demonstrates that research to quantify species that rely on TNC preserves can produce useful insight for efforts to understand and improve other habitat types—in the San Pedro River basin, across Arizona and beyond.