Study: Digital Tree-Marking Methods Speed Up Forest Management and Reduce Costs

Protecting nature starts with science.

In 2025,

TNC Forest Program staff, a TNC Scientist, and partners published Innovative Tree Designation Methods for a Complex Silvicultural Treatment in the Journal of Forestry.

In the majestic ponderosa pine forests of northern Arizona, the rhythmic, upward-trilling calls of Swainson's thrush mixes with the frenetic whistles of mountain chickadees. Pine needles coat the ground, the source of the sharp-fresh smell on the wind. Dappled shadows of the canopy fall on diverse grasses that thrive in the open spaces among trees—some old and wide, others small enough to span with two hands.

The Sounds of the Forest

Mountain Chickadee by Wil Hershberger; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

A pair of mountain chickadees is interacting and the male is singing.

Quote: Journal of Forestry, 2025

Southwestern ponderosa pine forests are the dominant natural forested community over millions of hectares in Arizona, New Mexico, southern Utah and southwestern Colorado.

The Challenge

Over time, the opportunity to experience a healthy ponderosa pine forest in Arizona has significantly diminished. Expansion-era changes in land use, such as clearing for livestock grazing, was followed by the cessation of Indigenous cultural burning and the suppression of natural fire ignited by lightning. During the last century, those combined circumstances have resulted in dense, single-age forests with dangerous quantities of accumulated dead wood and pine needles on the ground. In addition, the hotter, drier weather patterns of recent decades have all converged to one outcome: many areas are one spark away from devastating wildfire.

Thinning trees is a common practice to reduce fuel and restore balance in a forest—but it is expensive, and not an easy task.

Reducing tree density typically requires skilled technicians to make their way to remote areas. They move across rough terrain with heavy cans of bright orange paint, pausing to mark individual trees. It is slow, hard work. But to prevent wildfires, it has been necessary work—until now.

Science in Action

The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service came together to find a better way. Researchers from Northern Arizona University and Paul Smith's College Institute of Forestry joined the effort to test tree marking methods.

“We want to accomplish as much as possible as quickly as possible with the resources we have,” said TNC Arizona Forest Program Director Joel Jurgens.

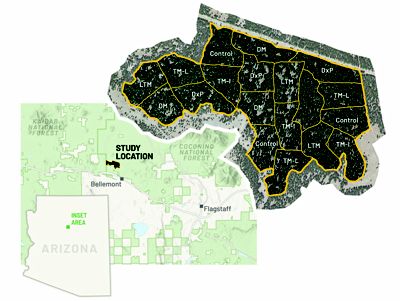

The partners zeroed in on the Coconino National Forest, which spans more than 1.8 million acres and includes Humphrey's Peak, the highest point in the state. The forest surrounds the towns of Sedona and Flagstaff and borders four other national forests. TNC and the Forest Service conceptualized how to use different kinds of imagery and communications tools to guide harvesting less desirable trees and leaving old-growth specimens and hardwoods like oak or aspen. A 410-acre area of the forest known as Walker Hill was divided into three blocks. Each block was subdivided into six sections. A different method was used to guide tree thinning in each section:

What is LiDAR?

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) is a remote sensing technology. Lasers mounted on airplanes emit pulses. The amount of time it takes for them to reflect off objects and return to a sensor is measured and analyzed to create highly detailed 3-D maps.

- Traditional Leave-Tree Marking (LTM): Technicians make decisions on-site and mark trees to leave with paint. A harvesting crew follows later, leaving only the trees that are marked.

- Designation by Prescription (DxP): A harvesting machine operator selects trees to remove based on a written description of what to cut and what to leave, considering the arrangement of trees to clear openings and create healthy groups.

- Imagery-Based Tablet Marking (TM-I): A forest technician in the field creates a map on a tablet using satellite imagery to indicate areas to avoid, which is then given to a harvesting machine operator to guide tree removal.

- LiDAR-Based Tablet Marking (TM-L): Similarly, maps to guide harvesting are created in the field using LiDAR data—which is 3-D imagery that indicates the height of the forest canopy.

- Desktop Marking (DM): A harvest plan that combines satellite and LiDAR data is created from anywhere on a computer, which is then shared with crews in the field on a tablet.

- Each block also contained a control unit, or a section that was not treated for comparison.

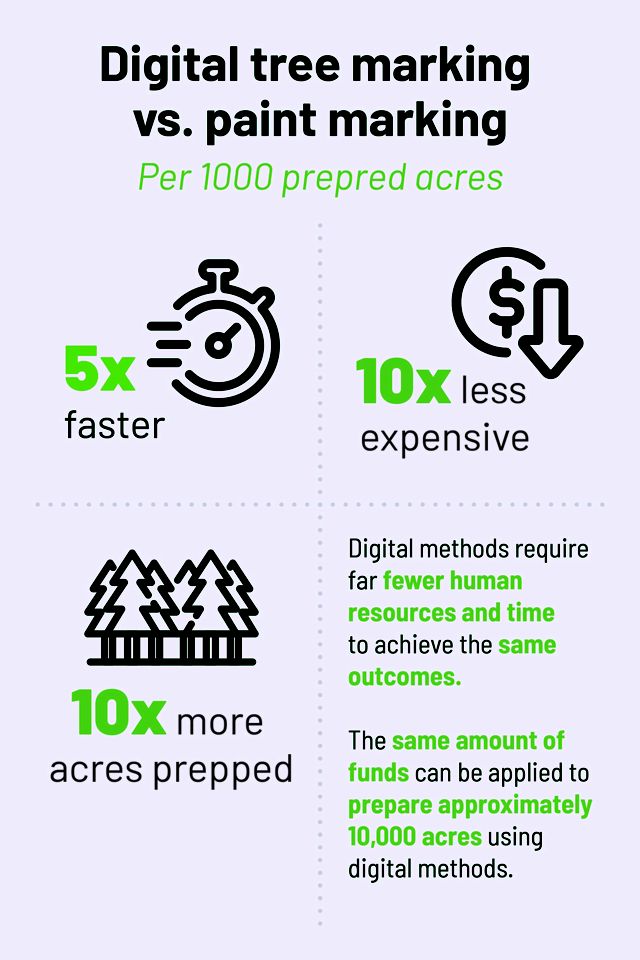

The results were published in the Journal of Forestry in 2025. Innovative Tree Designation Methods for a Complex Silvicultural Treatment is the first rigorous scientific study to assess digital tree marking techniques. It soundly documents how practices using technology can save time and costs associated with thinning forests.

The Results—And Why They Matter

The different methods for designating trees to thin led to comparable improvements in forest health. However, digital tree-marking methods allowed for dramatically faster work in preparing project areas for thinning.

Across U.S. western forests, wildfires are on the rise—in frequency and severity–and they are harder to fight because of extreme conditions. Communities in high-risk regions are experiencing myriad adverse impacts, from the loss of life and property to the mental health consequences of trauma as evacuation orders and fear occur more often. Smoke from fires travels, lowering air quality hundreds of miles away. Public and private land managers are seeking cost-effective methods to accelerate the number of acres treated with preventive measures—and that’s why the Walker Hill study is so important.

“A hallmark of TNC is our commitment to learning from each other across borders and sharing our research with partners,” said Travis Woolley, TNC Arizona’s forest ecologist. He reports that colleagues working in multiple states and regional initiatives, such as the Western Dry Forests Program, agency partners and Tribal nation representatives have reached out with questions about the digital tree-marking study. “This project provides hope that we can protect forests and people at a meaningful scale.”

We are grateful for the partnership and expertise of the authors of Innovative Tree Designation Methods for a Complex Silvicultural Treatment:

- John D. Foppert, Institute of Forestry, Paul Smith’s College, New York

- Neal F. Maker, Forest Biometrics Research Institute, Oregon

- Kristen M. Waring, School of Forestry, Northern Arizona University

- Travis Woolley & Joel A. Jurgens, The Nature Conservancy

- Mark R. Nabel, USDA Forest Service, Coconino National Forest

- Jeffrey Rainey, Colorado Forest Service, Colorado State University