Inside the Alien Worlds of Vernal Pools

Each year, thousands of newly metamorphosed frogs and salamanders emerge from seasonal pools that are as threatened as they are ephemeral.

Summer 2021

A long trek on a dirt road atop the Cumberland Plateau leads to a pool no larger than a living room. Its surface is a dark mirror, reflecting oaks and hickories and patches of Tennessee sky. Rotting leaves and branches sit at the muddy edges of the water; from the outside, all seems quiet and still.

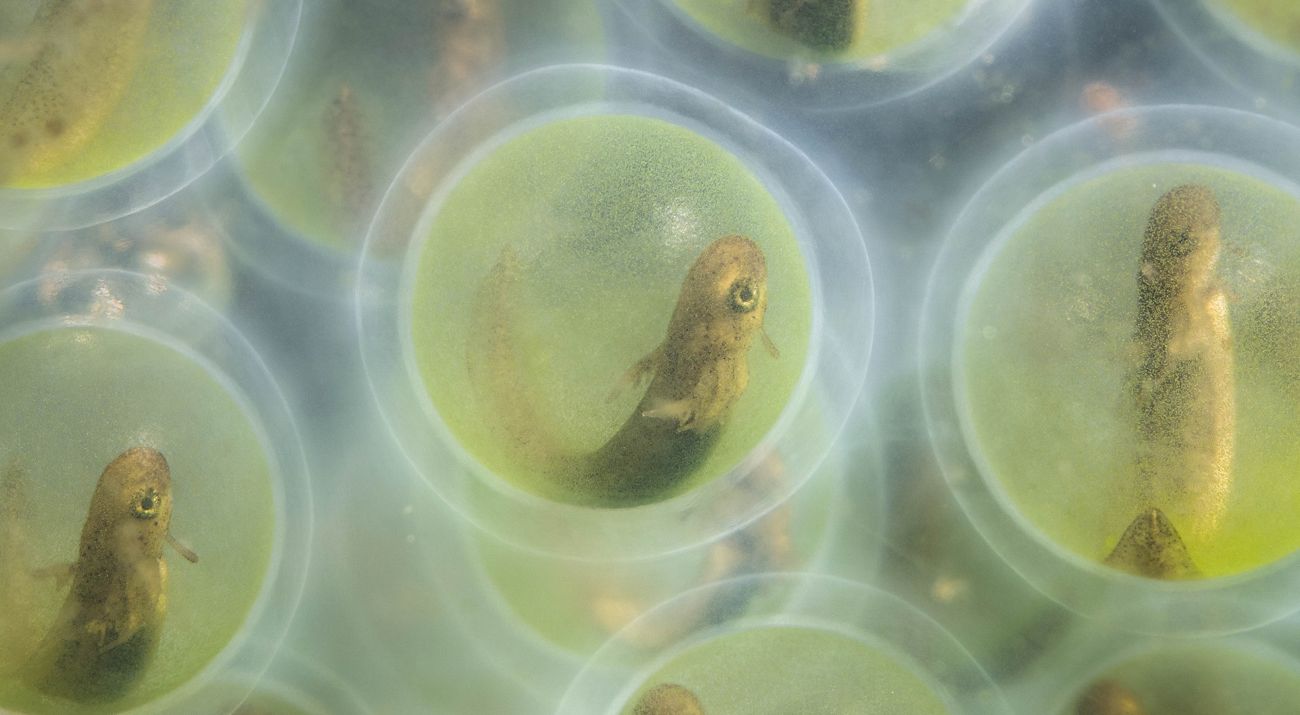

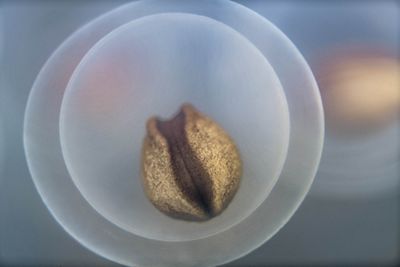

Beneath the water’s surface, spotted salamander eggs glisten pale green. Pickerel frog and spring peeper tadpoles search for algae. It’s late winter now; in a few months, the amphibians will test their terrestrial limbs, climb from the pool and disappear into the forest. Pools like this, crucial for their surrounding ecosystems and the animals that populate them, once dotted the Appalachian Mountains and foothills. But now, their number is declining.

Known as vernal pools, these seasonal wetlands are mostly dry in summer but fill with rainwater and snowmelt in the late fall, winter and spring, when the clay beneath the topsoil is saturated enough to hold water. Though they vary by geology and location, the ephemeral nature of vernal pools keeps them free of fish, making them a vital breeding ground for invertebrates and amphibians, whose life cycles are perfectly synchronized with the annual cycles of the pool—cycles now at risk from climate change and development. Legal protection for these ponds is murky; it’s difficult to protect something that isn’t always there.

“A normal person would walk across a vernal pool and have no idea whatsoever that anything lies beneath that blackness,” says Michael S. Hayslett, a Virginia vernal pool ecologist. “But beneath the veil lies a truly fantastical world.”

A Link Formed by Evolution

Vernal pools come to life in the fall, when marbled salamanders arrive during nighttime in droves to breed and lay eggs in the dry depressions. “They are just betting that these pools will fill,” says JJ Apodaca, a North Carolina herpetologist. “Once they do, the eggs hatch and get a head start in growth on larger species, like tiger and spotted salamanders, which arrive sometime between December and February.”

Wood frogs lay eggs by the thousands, and pool-bound fairy shrimp hatch in midwinter. By late winter and early spring, the pools are teeming with life that will flow out into the surrounding forest as the amphibians metamorphose.

Thousands of years of evolution have tied these species, called obligates because of this dependency, to vernal pools’ annual cycles. Along with the many other species that use vernal pools—like newts, spring peepers and even some mammals—these obligates make up a large percentage of the biomass in their respective ecosystems.

Amphibians, Apodaca says, prop up the food chain, forming the link between invertebrates and larger vertebrates, including birds and mammals. “Sure, there is often only a little bit of water in a vernal pool,” he says. “But it’s enough to sprout an extremely complex ecosystem that is disproportionately important to the health of the forest.”

The Race to Save Vernal Pools

Already, though, innumerable vernal pools have been dredged, drained or simply built over, and how climate change will impact them is still unknown. Even small shifts in precipitation patterns can alter their hydrology and timing, causing a mismatch with the species that have evolved to keep pace with them. Protecting the remaining vernal pools, in all their diversity, is therefore critical, says ecologist Hayslett.

Hayslett is part of a community of ecologists and herpetologists protecting the vernal pools that remain by documenting them, conserving surrounding forest habitat as “buffer zones,” and in some cases building new pools. Hayslett helped secure protection for JK Black Oak Wildlife Sanctuary in Virginia, a property with more than a dozen vernal pools. Meanwhile, this year in North Carolina, Apodaca, working with The Nature Conservancy, plans to build 10 pools on Phoenix Mountain, located in a global hot spot of amphibian biodiversity.

New Science

Even as conservationists race to preserve vernal pools, scientists are still learning about the species that rely on them. In 2016, Ryan Kerney, a biology professor at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania, constructed seven vernal pools not far from his laboratory, with the help of TNC. There, spotted salamander eggs grow as they do across Appalachia, tinged with green—a clue to one of the most fascinating known symbiotic relationships. A green algae called Oophila lives within the spotted salamander egg capsules and within embryonic cells and tissues, photosynthesizing and allowing the salamander to grow faster and larger. Kerney is investigating the chemical signaling that induces the algae to move into the cells, and how it might play a role in salamander tail regeneration—one small step toward solving the remaining mysteries of vernal pools.

“The health of these forests is built upon abundance, and abundance is what vernal pools do best: Life in them gathers, forms, grows and then disperses, spreading like a glue that holds the ecosystem together,” says Apodaca. “When we protect vernal pools, we protect more than frog calls, fairy shrimp, and amazing symbiosis: We protect the essence of an Appalachian forest.”

Get the Magazine

Sign up to become a member of The Nature Conservancy and you'll receive the quarterly print edition of the magazine as part of your membership.