The Guardians

In northern Canada, a First Nation community is asserting its people’s rights and authority over 6.5 million acres of their traditional homelands.

Summer 2021

Just below the Arctic Circle, Canada’s boreal forest is home to a First Nation village of fewer than 400 people reachable only by boat, plane or snowmobile. There are no roads connecting the town of Łutsël K’é to its neighbors. The waterways that stitch the landscape together are simultaneously highways and hunting grounds, connectors and delineators. Before the 1950s, when people began to concentrate around what is now Łutsël K’é (then called Snowdrift), the Łutsël K’é Dene lived nomadically across their traditional territory, which spans roughly 41 million acres.

Here, winter temperatures linger for most of the year, and “freeze-up” and “thaw” are seasons like spring or fall. During the summer months, Łutsël K’é averages around 20 hours of daylight. In the winter, it’s more like seven. The average high between November and March is 5.2 degrees Fahrenheit.

“It is a fierce landscape: minus 30 degrees with wind blowing on the boreal forest tundra edge is not a light experience,” says Tracey Williams, Northwest Territories conservation lead for Nature United, The Nature Conservancy’s Canadian affiliate. Williams—who now resides in Yellowknife—lived in Łutsël K’é for 12 years, a blink compared with the First Nation that calls this region home.

Musk oxen and moose, grizzlies and wolverines, red foxes and snowshoe hares also thrive in the frigid conditions beneath the towering pine, spruce and broadleaf trees. The landscape is a breeding ground for millions of birds, supports approximately 32,000 species of insects and is a refuge for two subspecies of threatened caribou.

In 2019, 6.5 million acres of this globally significant ecosystem were protected—roughly half were designated Canada’s newest national park. The protected area, located in the country’s Northwest Territories on the east arm of the deepest lake in North America, was named Thaidene Nëné (thy-DEN’-ay nen-ay), which means “Land of the Ancestors” in the Łutsël K’é Dene’s Dënesųłıné language.

The Łutsël K’é Dene have grappled with threats to their ancestral lands for generations. The mining industry has long made claims on the region rich in diamonds and precious metals. Increasingly, climate change is impacting the landscape, which stores 379 million tons of carbon.

But North America’s history of colonization and postcolonial land management was perhaps the biggest hurdle to securing formal protections for the traditional territory of the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation. In Canada, a major step toward independence from the British Empire was followed swiftly by the Indian Act of 1876, which limited the self-governance of First Nations people and forced assimilation. Many First Nations people were confined to reservations.

“In the past, [the Canadian government] drew a line on a map and said: ‘You’re out.’ No one ever asked people there, ‘How would you like to show up in this space?’” says Williams.

Forging a new vision of conservation—one conceived around cooperative management, predicated on respect for ancestral territory, and dedicated to preserving a First Nation’s traditional ways of life—would require years of hard work and an unprecedented partnership.

Parks Canada (an agency of the Canadian federal government) first proposed the idea of the national park in 1969. It was rejected by Łutsël K’é Dene leaders because historically, a national park designation signaled the removal of Indigenous people from their ancestral territories and prohibitions on traditional activities like hunting, fishing, gathering of ancestral medicine, and visitation and ceremony at cultural sites. Trauma triggered by Canada’s long history of colonialism—which included forcing Indigenous children to attend federally funded schools that promoted cultural genocide—reverberates across generations of First Nations like the Łutsël K’é Dene.

[Text continues below]

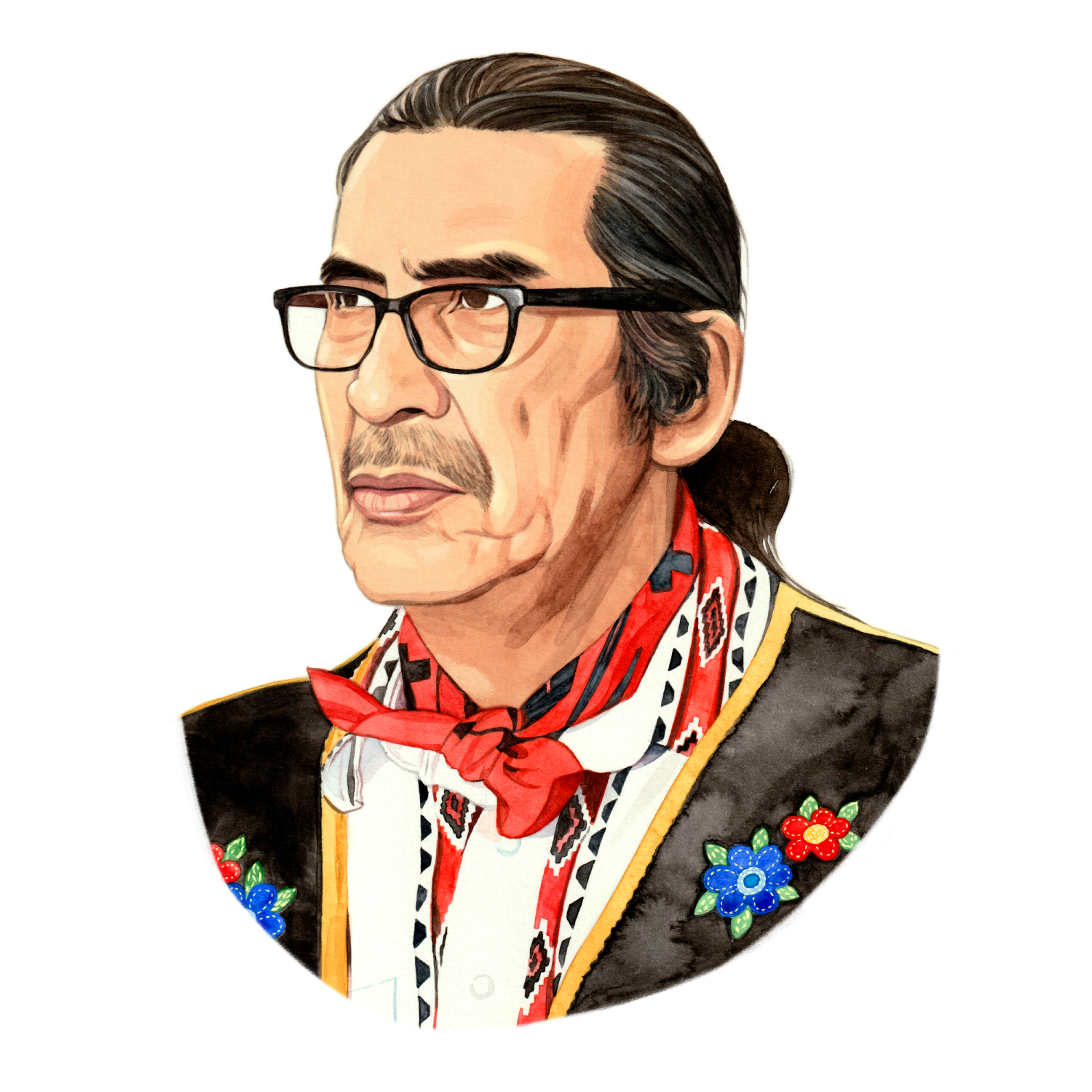

JC Catholique, Board Member, Thaidene Nëné Xá Dá Yáłti

The Łutsël K’é community worked for generations to protect their traditional territories in a way that preserved their relationship with the land, water and wildlife. In 2019, through an innovative model of Indigenous-led conservation, the Łutsël K’é Dene assumed a leadership role in the management of Thaidene Nëné—the newly protected heart of their ancestral lands.

"Every time I go to Ts’ąkuı Theda area ['The Old Lady of the Falls'; scroll down to read the story], it brings me back in time. That’s where my family comes from. It’s my homeland. Everything is clean and quiet. There are all kinds of wildlife.

"The Elders said, ‘Find a way to protect that area.’

"So, over the years, the community talked about it. They said maybe we should go with the idea of having a national park. They didn’t like the idea at first. But as development started to happen with the diamond mines, people got concerned because wildlife got impacted. The caribou did not come to the community as before. It opened up people’s minds to the damages that development can cause to the land, water and wildlife.

"We had public meetings about it throughout the years and eventually the attitudes started to change. We can work with Parks Canada, and we can work with the Government of the Northwest Territories. But our traditional laws have to come first. That’s the only way that people agreed to the park.

"People really wanted that land, Ts’ąkuı Theda, to be protected. For us, everything on the land is sacred, especially where the Old Lady sits at the falls. It’s a spiritual site.

"I’ve traveled lots. Been to Germany, the States, around Canada, throughout the Northwest Territories. There’s no place like Thaidene Nëné. The water is so clear. This is a place where you can go to a lake and drink directly from it.”

The Old Lady of the Falls

For the Łutsël K’é Dene, oral tradition is the way stories, customs and knowledge of the land and culture are carried from one generation to the next. One story harkens back to a time when giant animals roamed the Earth. Driven by great hunger, Łutsël K’é Dene harvested a massive beaver. An elderly Dene woman asked for some of the beaver’s blood but was denied because there was not enough to go around. When her people moved on, she was left behind. There are many interpretations of what happens next. In one version, the creator asks the woman to remain for eternity—ensconced in rock near modern-day Parry Falls—and provide guidance to anyone who visits her. Today, the Łutsël K’é Dene make summer pilgrimages to the Old Lady of the Falls (known as Ts’ąkuı Theda) along the Lockhart River, to pay their respects, ask for help and tap into the water’s healing properties. Reverence for this grandmotherly figure and her ecosystem has been a driving force behind the community’s efforts to protect the land, water and animals of Thaidene Nëné.

“My dad said boarding school destroyed Dene people,” says JC Catholique, an Elder of the Łutsël K’é Dene. “It took their language, their history, their way of life, their connection with the land, their connection with their family and their stories. A lot of those things weren’t passed on.”

But as the region’s unique geology drew renewed interest from mining companies in the 1990s, the community reconsidered. Elders issued a mandate to protect Łutsël K’é Dene territorial homelands and reengaged in negotiations. This time, Łutsël K’é Dene leaders voiced a desire to imagine, articulate and manifest what protection would look like—including taking a seat at the management table.

Negotiations worked in fits and starts. In the midst of the process, responsibility for public land, water and resource management in the Northwest Territories was transferred from the federal government to the region’s territorial government. Interests then had to be balanced across a triumvirate that included Parks Canada, the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation.

Doris Terri Enzoe, Sub-Chief, Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation

The Łutsël K’é Dene survive on hunting, fishing and trapping. Traditional knowledge is passed down from one generation to the next. Programs that support monitoring of the land promote this intergenerational learning.

"I was born in the barren lands [tundra], then we moved to Fort Reliance and then Snowdrift [Łutsël K’é]. In fall time, me, my brother, my mom and my dad would go out trapping until Christmas because that was the only way to feed your family.

"Now I have one girl, three boys, five grandsons and one granddaughter. There’s a place near the falls where we go fishing all the time. We go crazy for fish. When we see a moose and shoot a moose, it’s even more exciting.

"The Elders decided years ago that we should have something for our young generations, to protect the land for them because development was coming and it might destroy our water, our animals. My sister, Gloria, was working with the Elders then. She started Ni Hat’ni Dene (Watchers of the Land).

"My son Kyle and I applied. You can bring young girls and young men out to teach them how to live off the land. We showed them spiritual places, burial sites, the places where our ancestors used to live. We showed them where you have to be quiet, where you have to pay [respect to] the water. We showed them that this is a good place for stopping when it’s windy. This is a good place for fishing.

"Kyle was with Ni Hat’ni for 14 summers. I was with them for 10. The life cycle has all changed since I trapped with my family as a kid—it’s so different—but we still have to keep our old ways of living if we want to keep Thaidene Nëné.”

“Once Łutsël K’é solidified their vision for protecting their ancestral lands, they realized this would only be half the battle,” says Williams. “They would need to share that vision with the world—and there might be organizations that could help them build momentum for their work.”

In 2009, the Łutsël K’é Dene invited TNC to provide technical support in service of that goal, including mapping the ecological and cultural values of the proposed protected areas. The organization also leveraged political and fundraising connections to advance the designation efforts led by the First Nation.

Denecho Catholique, Ni Hat’ni Dene Guardian

The Łutsël K’é Dene leveraged the Thaidene Nëné Trust to expand their existing Ni Hat’Ni Dene guardian program to a year-round operation. The program offers summer internships for young people aged 18 to 24 to help them cultivate skills—such as navigation, harvesting plants and animals, and reading the weather—that will prepare them for careers as caretakers of their environment.

"I’ve been going out on the land ever since I was little, and now it’s my job.

"As Ni Hat’ni Dene guardians, we go out in pairs. We monitor wildlife as well as hunting practices. We observe environmental changes, the weather and visitors in Thaidene Nëné. We also protect cultural areas.

"For me, it’s like a dream come true. I have an awesome job. I rarely stay in the office. Out in the bush—out on the land—is my office. I enjoy the work.

"We have really rich land. Especially the barren lands. It’s like a whole different country. Everything out there wants to eat you—bears, wolves. Every hill looks the same, so it’s easy to get lost. But that’s how I learned to navigate and hunt.

"You’re not allowed to say “beautiful” when you go up to the barren lands, the Elders get mad because when you say it’s beautiful, you’re asking for bad weather, they say.

"I hope to [continue developing] this program for the younger generations. As a monitor, it feels like it’s my responsibility to show the younger kids how to get involved. Us Dene people, we are strong. We stick together, as a community.”

Listen to Denecho Catholique

The Ni Hat’ni Dene Guardian program teaches young people how to steward the land, waters and wildlife of Thaidene Nëné.

TBD

Finally, in August 2019—50 years after the government of Canada first proposed the idea—an agreement was reached to protect Thaidene Nëné as part national park reserve, part territorial protected area and part wildlife conservation area. Honoring the vision of Łutsël K’é Elders and leaders, Nature United helped establish a trust that will steward Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area into the future. The trust was capitalized at $15 million and matched by the Government of Canada for a total of $30 million. Each year, the trust is expected to generate approximately $1 million in interest that can be used to support the Łutsël K’é Dene’s management of the protected area, including trainings, planning, research, monitoring and education. In the spring of 2021, the first disbursement from the fund was made to the community.

Iris Catholique, Thaidene Nëné Manager, Advisor To Thaidene Nëné Xá Dá Yáłtı

Appointees from the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation, Parks Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories serve on a management board—Thaidene Nëné Xá Dá Yáłtı—that oversees all 6.5 million acres of the Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area.

"I think it’s really important that the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation is part of the management board because it’s leading the way for how things can be managed in partnership, as opposed to how things have been run within Canada over the last 150 years. This model for Thaidene Nëné has been set up so it’s very respectful of our Indigenous and Treaty Rights. It’s all based on a consensus decision-making model.

"[The management board] is going to be dealing with everything from the development of trails—where those locations will be—to helping the territorial government decide whether different operators are allowed. They need to complete baseline assessments of ecological integrity and make sure that those areas stay preserved.

"They also need to select different locations for where we’re going to enhance our infrastructure within Thaidene Nëné. Our Ni Hat’Ni Dene guardians are planning to build a new cabin in the Fort Reliance area so we can have year-round monitoring of people and their use of the land.

"I’d like to see this community become self-sustaining. We have all of the resources. We just need to build capacity within our young people to fully work, operate and live within the park and to promote it.

"We’ve been reaching out a lot more, enhancing our web page and our newsletters. Just trying to keep people connected and aware of what we’re doing and what our plans are. I want the world to come visit Thaidene Nëné and see how beautiful our people are and the deep connection we have with the land.”

For conservation in general, this is a really excellent example of Indigenous people driving outcomes they’re seeking,” says Jenny Brown, director of conservation for Nature United. “It’s also a good example of what that takes. It’s a long-term commitment.”

Designation was just the beginning. Today, Thaidene Nëné is helping the Łutsël K’é Dene diversify their economy while preserving their ancestral lands for future generations. Renovations are underway on the Frontier Lodge, purchased by the community in 2020. The lodge and other tourism-focused businesses that develop around the protected area will create jobs and provide educational opportunities for visitors. The designation of Thaidene Nëné also allowed the community to expand their environmental stewardship program called Ni Hat’ni Dene, or “Watchers of the Land,” which transfers important cultural and ecological knowledge about the landscape from experienced knowledge-holders to younger generations. A crew of guardians tracks environmental changes on land and water throughout the protected area, interacts with visitors and maintains cultural sites. Recently, Nature United also provided technical support for the Łutsël K’é Dene’s plan for threatened barren-ground caribou, which will strengthen stewardship of wildlife across Thaidene Nëné and beyond.

Adeline Jonasson, Former Chief And Councilor Of The Łutsël K’é Dene

In addition to preserving the spiritual center of Łutsël K’é Dene culture, Thaidene Nëné will help improve and diversify the community’s economic future. In 2019, the community purchased the lakeside Frontier Lodge, which the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation is now transforming into an adventure hub that offers fishing expeditions and camping trips, as well as opportunities to view the northern lights and arctic wildlife.

"My interest in being an advisory committee member was to protect Thaidene Nëné. Along with other committee members, we ensured the land, water, animals were protected. We wanted to make sure that our way of life wasn’t disrupted and that we could continue to live as we have since time immemorial.

"We have the opportunity for our community to invest in the land in the way that is different from what others do. For example, we purchased the tourist lodge that is only about five minutes outside the community. We’re hoping that we’ll have more people employed there.

"In 10 years, if you call me, I would say: You need to come and visit our tourist lodge. You can come in the summer or the winter, because it’s a year-round tourist lodge now. And then you can come over to the community and check out our museum that we have here, that will give you the history of the area. You’ll see the beautiful handcrafts that the community women and men have made. Come and take a trip, because we have outpost camps into Thaidene Nëné. Or in the wintertime, people in the community have dog teams that will take you out and you will see aurora borealis.

"That is what is going to sustain our community. The mines never did. But Thaidene Nëné? Thaidene Nëné will be here forever.”

Listen to Adeline Jonasson

Managing the Frontier Lodge is one way Thaidene Nëné is diversifying the Łutsël K'é Dene First Nation's economic opportunities.

TBD

The path to Thaidene Nëné has not been easy, but the precedent it establishes is far-reaching.

“If you see Thaidene Nëné as a continuum of Indigenous people building their rightful place in management and governance models, it holds promise for others to build on,” Williams says. “We can build better paradigms if people of place are involved directly.”

Get the Magazine

Sign up to become a member of TNC and you'll receive the quarterly magazine.

Subscribe now