Balancing Act A hunting ocelot is a triple threat—it can snag its prey on the ground, in a tree or from the water. Small rodents and reptiles are common quarry. © Charlie Hamilton James

In 1999, a strange virus began to afflict pig farmers in Malaysia. Patients suffered headaches, fevers and brain inflammation; ultimately more than 100 Malaysians died. Named the Nipah virus for the village where it was first identified, the pathogen is carried by fruit bats, which had been driven from their natural habitat by deforestation and fire and were foraging in orchards surrounding pig farms. It is believed that the bats were transmitting the virus to pigs, which passed it to humans. Nature’s deterioration, it seems, had spawned a public health crisis.

Bugle Boys

Few large mammals are as expressive as elk, which grunt, squeal and bark to communicate within their herds. The species’ most famous call is the bugle, an eerie trumpeting that males utter to court females or challenge rivals for breeding privileges. The deeper the bugle, the angrier the elk. Males can even be recognized by their unique bugles.

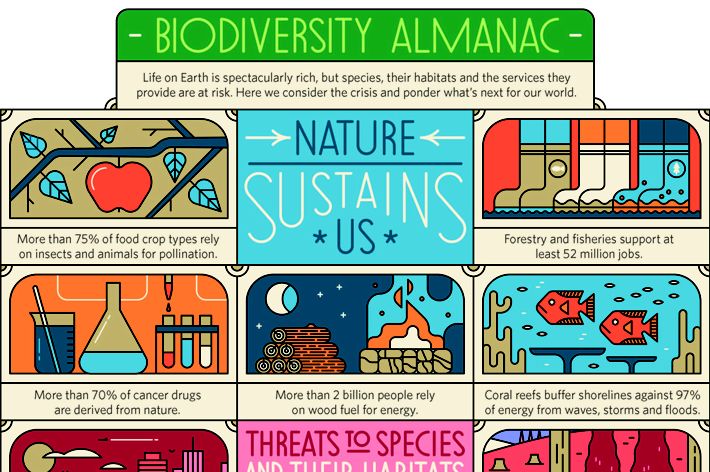

The Nipah virus spillover provided evidence of a profound truth: Our fate is inextricably linked to the biodiversity that surrounds us. Insects pollinate our crops; oceans feed us; forests provide us with shelter. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the fact that when nature suffers, human well-being follows suit—loss of habitat and more contact with wildlife increases the risk of transmitting zoonotic viruses to humans. “Healthy waters, healthy lands, healthy people—all are part of a cohesive and integrated whole,” says Lynn Scarlett, chief external affairs officer for The Nature Conservancy.

Gator Chomp

Alligators aren’t just apex predators in the freshwater swamps and marshes of the southeastern United States—they’re also ecosystem engineers. The “gator holes” that they excavate hold water during the dry season, creating vital oases for fish, herons, frogs and otters.

To keep that whole intact, delegates from nearly 200 countries will convene for the next meeting of the United Nation’s Convention on Biological Diversity, which will set global priorities for safeguarding habitats, saving species and protecting the ecological services that sustain human communities. Although a date for the convention is uncertain due to global travel restrictions at the time of publication, its mission couldn’t be more urgent. Since the late 19th century, the world has lost approximately half of its coral reefs, and other critical ecosystems, like wetlands and tropical forests, are shrinking fast. Around 1 million species are threatened today with extinction. “The arc of conservation is at a pivot point,” Scarlett says.

Baby Blues

Scorpions like this rock scorpion, photographed while illuminated by ultraviolet light, give birth to live young and the mothers are exceptionally devoted. The female carries her offspring, known as scorplings, on her back for weeks, until their exoskeletons harden and they’re ready for life on their own.

To meet that challenge, a suite of innovative conservation strategies has evolved. Consider what happened in 2020 when a hurricane bludgeoned a coral reef in Mexico with wind speeds exceeding 100 knots. The damage from Hurricane Delta triggered a payout of about $850,000 from an insurance policy, taken out by the state of Quintana Roo with TNC’s assistance—perhaps the first such policy ever purchased on a natural feature. Within days the funds put locals to work cementing corals back into place and planting new colonies, rebuilding the living sea wall that will defend their coastline from future storms.

“We have increasingly come to realize that we can’t just create a preserve and put our picket fence around it,” Scarlett says. “And that means we need to be engaging a world of environmental stewards.”

Along Came a Spider

The world’s heaviest spider, the goliath birdeater weighs up to 6 ounces—more than an average-sized avocado. In spite of its name, it rarely eats birds, as it prefers insects, worms and frogs. This tarantula is armed with inch-long fangs and barbed hairs that it can send flying at assailants.

But using out-of-the-box tactics and working with local partners are only half the battle. Tackling the scope of today’s mass-extinction crisis—the most severe since a hunk of space rock is believed to have set the dinosaurs on a crash course toward oblivion—requires a global perspective. Animals from gray whales to monarch butterflies cross national borders during their migrations; invasive species leap between continents; and climate change casts its net over the entire planet. The high seas, the vast expanse of ocean that lies beyond any nation’s territorial waters, have long been virtually lawless. But since 2018 U.N. delegates have been negotiating a treaty that would conserve and protect marine diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction—proof that international consensus is possible.

A Bug's Life

Moths like the Deyrolle's emperor moth are our planet’s nocturnal support staff: Scientists describe them as “secret pollinators” that sustain hundreds of plants, and their bodies feed birds, bats and even bears. They may be less conspicuous than butterflies, but they’re remarkably diverse: More than 11,000 species flit through the United States alone.

Pest Management

The biological sonar that bats use to navigate and hunt is called echolocation. A bat closing in on an insect may emit and interpret up to 200 sonic pulses each second. A hungry bat is an exterminator without equal: Researchers estimate that bats provide the equivalent of more than $20 billion in insect-control services each year.

Scarlett is counting on the upcoming conference to ratify a similarly bold global vision: a commitment known as “30x30,” under which nations would pledge to protect 30% of their lands and seas by 2030. She also hopes that the conference will create new conservation funding sources; a recent report by TNC and its partners estimates that at least $598 billion more per year is needed to stave off the collapse of nature’s systems.

Sunrise Ceremony

The courtship ritual performed by the sage-grouse, the icon of western North America’s sagebrush plains, is one of nature’s most dramatic. Males woo hens at display sites, called leks, fanning their tails and inflating their breast sacs. For decades, TNC has worked with ranchers and energy and mining companies to protect the grouse’s stage in the sage.

On the Move

The home ranges of black bears (like this one traveling a game trail in Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest) can cover a lot of ground: A male’s territory might be more than 300 square miles. In Florida, TNC identified and is safeguarding wildlife corridors so that these intelligent omnivores have room to roam.

Fulfilling such lofty objectives won’t be easy—the world failed to achieve the previous targets the convention established in 2010. But signs of hope are not hard to find: At least 17% of land and inland water worldwide is already protected, and as much as 80% of the world’s forest biodiversity can be found on the lands of Indigenous peoples, who make up less than 5% of the global population. Conservation efforts have pulled dozens of species back from the brink, including the California condor and the Przewalski’s horse. And even as the window for preserving biodiversity grows narrower every year, we have no choice but to try. “When it comes to ambition,” Scarlett says, “more is better.”