Humboldt's New World

Two hundred years ago, a young scientist set off on a voyage of scientific discovery that would sketch a road map for the future of conservation.

July/August 2013

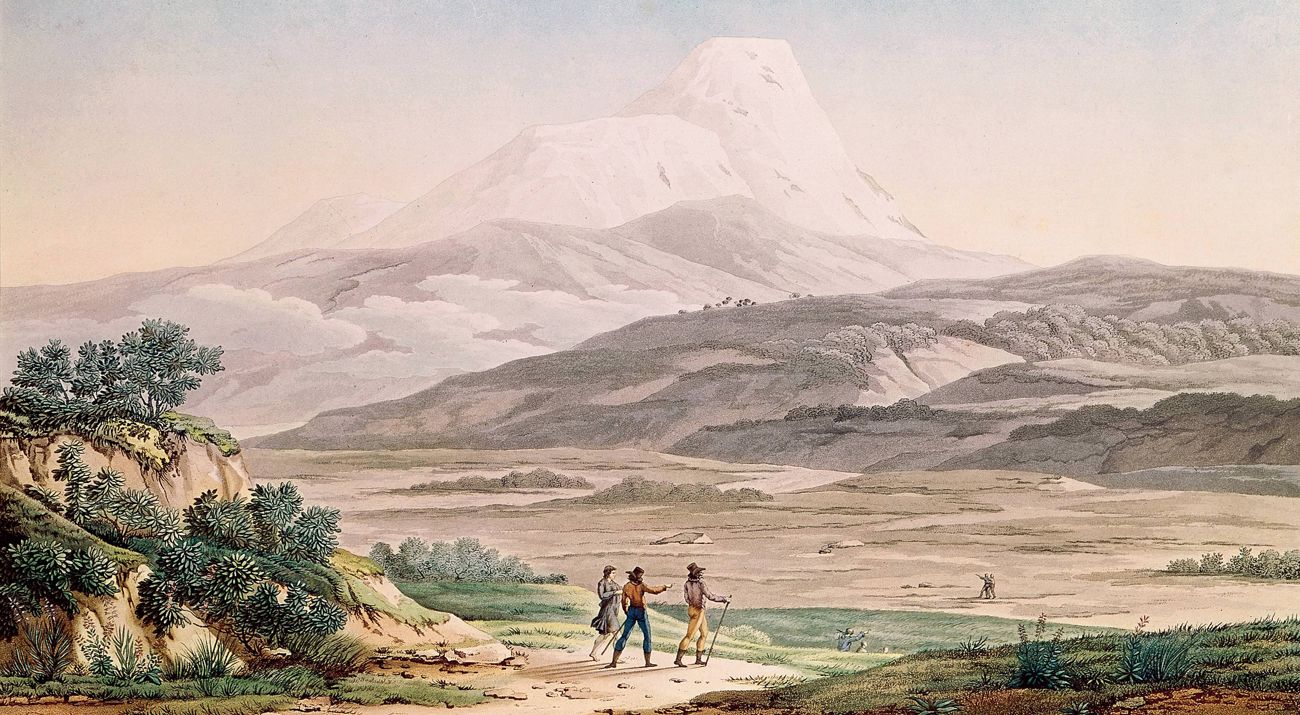

At 13,000 feet in Ecuador’s Andean highlands, two bumpy hours’ drive from Quito, stands a decrepit building with an astonishing view. Sitting on land The Nature Conservancy helps protect, the structure is crumbling, and its rafters are covered with guano deposited by two resident owls. Outside, the ice covered vision of the 18,874-foot Antisana Volcano, just four miles away, is enough to stop conversation. A plaque by the door explains why the building has not been torn down: In 1802, one of the most famous scientists in the world slept here, no doubt having marveled at the same view.

The Prussian naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt was midway through a five-year, 6,000-mile voyage of scientific discovery through Latin America that would revolutionize thinking in fields from astronomy to zoology. Charles Darwin himself called Humboldt “the greatest scientific traveler who ever lived,” and when Darwin set off on his own journey aboard the Beagle three decades later, he took a copy of Humboldt’s seven-volume travel narrative.

Two hundred years later, it’s no coincidence that Humboldt’s route leads through many places the Conservancy is working to protect. His quest to collect enough information to assemble a unified theory of the natural world led him to some of the most biologically distinct regions in the Americas: over icy peaks, through wild grasslands, up jungle rivers and across rich ocean currents. Today, many of the landscapes that inspired one of the world’s greatest thinkers are under threat, and together they form an atlas of much of the Conservancy’s work in the northern parts of South America.

“All this is my office," says Byron Mosquera as he sweeps his arm across the view of the towering peaks surrounding Humboldt’s humble lodging. Mosquera works as a guard for the Quito Water Protection Fund, the first of its kind in Latin America. Launched in 2000 with funding from the Quito Water Company and the Conservancy, the fund addresses one of Ecuador’s most serious conservation issues: protecting the water supply for the 2 million people who live in its booming capital.

Quito’s residents consume 7 cubic meters of water every second, enough to fill 242 Olympic swimming pools every day. Almost all of this water originates high in the Andes, in places like this. But not all of these places are protected.

Mosquera points to a hillside covered with short grass, site of a recent restoration project. “That used to be all sheep.” Before the water company bought and protected the land, its private owners grazed thousands of sheep here, which left the high-altitude grassland denuded and prone to erosion.

“You can imagine it was not in good shape,” says Oswaldo Proaño, a project coordinator for the fund.

Several of the old hacienda buildings near Humboldt’s shack have been converted into guards’ quarters. The new entrance gate is under construction, requiring vehicles to drive around it to visit the preserve. A short drive away, clouds slide over gray-green hillsides around Lake Micacocha, which supplies drinking water to 700,000 Quiteños, making it one of the city’s largest water sources.

By most measures, the water fund has been a rousing success. The initial capital investment to start the fund ($20,000 from the Quito Water Company and $1,000 from the Conservancy) has grown to $10.8 million thanks to prudent investments and ongoing support from the water company, as well as additional contributions from the Conservancy, the city’s electric utility, the Swiss government, a local brewer and a water-bottling company. The fund now provides$1.5 million every year for conservation projects like the one near Antisana. The Conservancy has since established water funds elsewhere in Ecuador as well as in Colombia, Brazil and Mexico. The goal is to have 32 funds in operation by 2015, protecting the water supply for 50 million people.

Born in 1769 to an aristocratic Prussian family in Berlin, Humboldt was fascinated with the natural world from childhood. Thanks to his voracious intellect, he researched and published scientific papers on subjects as seemingly unrelated as the distribution of plants across different geographies and the physiology of electrical nerve impulses—all while working as a mine inspector.

Several encounters with famous scientists of the day planted the seeds of Humboldt’s distinctive scientific mindset: that the only way to understand the world was to look at it as a whole, using all the physical sciences together, instead of breaking everything down into isolated parts and disciplines—equal parts Gaia and Grand Unified Theory. “Knowledge and comprehension are the joy and justifi cation of humanity,” he wrote. Data were key; the more the better.

In 1799, Humboldt and the French botanist Aimé Bonpland set sail for South America aboard the frigate Pizarro. Along with 42 of the fi nest scientific instruments available—including barometers, telescopes and chronometers—they carried a commission from King Charles IV of Spain to make the fi rst detailed scientifi c exploration of Spain’s mostly uncharted colonies in the Americas. Even if the king’s motives were purely commercial—the better he knew his colonies, the more wealth he could extract from them—for the scientists it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

After a six-week voyage, the ship landed on the Caribbean coast of Venezuela in mid-July. (At the time, Venezuela, Panama, Ecuador and Colombia were joined in the Spanish Viceroyalty of New Granada.)

The scientists set out on the Orinoco River, the world’s fourth largest by flow. They spent the next 75 days struggling upriver in canoes, choking on mosquitoes and eating everything from ants to manatees. They documented the lives of native peoples, such as the Maipures, and conducted the first scientific experiments on electric eels. They determined the creatures could aim their 600-volt charge and found that holding hands transmitted the teeth-rattling shock.

In two and a half months, Humboldt and Bonpland traveled 1,500 miles to the river’s source, where they made the first of many major geographic discoveries: The Orinoco and the Amazon, South America’s two mightiest rivers, were connected by the Casiquiare canal.

Humboldt’s Orinoco journey took him through the “sea of grass” of the Venezuelan Llanos, one of the richest tropical grasslands in the world. Today, much of this expanse of rivers, marshes and seasonally flooded savannas is as wild as it was in Humboldt’s time. Jaguars, anacondas and giant anteaters share the forests with 700 species of birds, more than are found in the entire continental United States. The rivers teem with more than 1,000 fish species, including a 300-pound catfish called the lau-lau, as well as the endangered Orinoco crocodile, reduced to an estimated 1,500 in the wild.

Unlike in Humboldt’s era, this riot of life is now facing incursions from oil and gas developers, large-scale agriculture and illegal wildcat miners. In response, the Conservancy has teamed up with governments and local communities in both Venezuela and Colombia to help protect biodiversity and guide environmentally sustainable development.

In 1999, in one of its largest land donations ever, the Conservancy transferred more than 180,000 acres to the Venezuelan government for inclusion in Aguaro-Guariquito National Park, along the Orinoco. In 2012, Venezuela’s municipal government of Romulo Gallegos designated, in collaboration with the Conservancy, more than 1 million acres for “cultural and ecological protection” (see “The Changing Land,” March/April 2013). Other municipalities have expressed interest in copying the project, says Conservancy anthropologist Eduardo Ariza. “More than 20 indigenous peoples occupy large areas in the Llanos,” he says, “but still have no ownership over their territory.”

After a brief detour to Cuba, Humboldt and Bonpland arrived in Cartagena and in April 1801 started paddling up the Magdalena River, Colombia’s main waterway. They made the first chart of the river as they ascended, covering 600 miles in six backbreaking weeks to reach the settlement of Honda. From there it was 50 steep miles of walking to Santa Fe de Bogotá, capital of the Viceroyalty of New Grenada, at 8,660 feet in the Andes. Over the next two months, Humboldt ventured out from the city to measure the heights of mountains and examine fossilized mastodon bones while Bonpland recovered from malaria.

Although the Magdalena River basin covers only a quarter of Colombia, today it supports 80 percent of the country’s population and generates 86 percent of its gross domestic product. The lush riverside vegetation that Humboldt and Bonpland struggled through at the height of the rainy season is now three-quarters gone, and fish catch has fallen 80 percent in the past 15 years.

The Conservancy has made the Magdalena a priority at a critical time, says Rosario Gomez, the Conservancy’s Magdalena River project coordinator. The government agency responsible for managing the river has proposed a series of projects to channelize and dam the river for hydropower. Gomez and her team are working with officials to develop an alternative: a riverwide management plan that balances infrastructure development with conservation.

The effort is still in its early stages, but as of the end of 2012, nearly 2,500 ranchers had signed up for a project designed to boost productivity while reducing deforestation and water contamination from fertilizers and herbicides. And after the success of Quito’s water fund, the Conservancy in 2008 helped set up a similar fund in Bogotá to protect lands that supply water to the city’s 8 million inhabitants. More funds are planned for Cartagena, Medellín and Barranquilla.

Humboldt, of course, had drawn a connection between healthy landscapes and water supplies during his time in Venezuela: He attributed the falling water levels in Lake Valencia, west of Caracas, to the clear-cutting of nearby forests.

The two explorers left Bogotá in September 1801 and headed south through the Andes. Four months later they arrived in San Francisco de Quito, now the capital of Ecuador. The city of about 40,000 filled a river basin at 9,360 feet at the base of an active volcano called Pichincha.

The Andes run down the middle of Ecuador like a knobby spine, with 10 peaks higher than 15,000 feet, including many active volcanoes. The main north-south route—today part of the Pan-American Highway—is an eye-popping slalom around gigantic peaks. Humboldt dubbed this extraordinary passage the “Avenue of the Volcanoes,” a nickname that has endured.

The explorers spent most of their time in Ecuador scrambling up mountains. On his fi rst try at Pichincha, Humboldt grew dizzy, passed out and had to be carried down. He was successful on his second and third climbs while lugging an array of instruments—barometers, hygrometers, electrometers—to study the 15,695-foot peak.

In Humboldt’s time the Andes were considered the highest mountain range in the world, and Ecuador’s Chimborazo (20,702 feet) was thought to be the tallest of them all. Humboldt and Bonpland tried to climb the mountain in June 1802, struggling so high their noses bled from the altitude. When they fi nally turned back at 19,286 feet, they had gone higher than anyone else in recorded history, even in a balloon. It was this record-breaking feat, as much as anything, that cemented Humboldt’s worldwide celebrity.

The most important legacy of the Chimborazo climb, though, is a diagram Humboldt made afterward showing which plants grew where on the volcano’s slopes, based on altitude, rainfall and soil type. In a single, richly detailed image, he showed that organisms at similar elevations and latitudes around the world tend to have similar traits and adaptations. It was classic Humboldtian science, blending concepts from biology, geology, climatology and ecology.

Today, fluffy llamas graze in the fields across from the new visitors center at the entrance to Chimborazo National Park on the mountain’s southern flank. The Conservancy helped design the buildings using local materials in a style that evokes chunky Inca stonework. The Conservancy also helped Ecuador’s Tourism and Environment ministries come up with a plan under which local indigenous communities will manage the center, benefit from the entrance fees and eventually run guided tours.

As the road climbs, the sound of the straining car motor sends vicuñas (smaller cousins of the llamas) bolting away across the barren slopes. At a climber’s hut at 15,900 feet, the icy air and the blinding sunlight are equally bracing. Families sit on rocks to pose for pictures, squinting into the wind. Behind the hut is a 20-foot stone pyramid bearing three plaques—one dedicated to Simón Bolívar, the George Washington of South America, and two to Humboldt.

After dipping into the upper Amazon, Humboldt and Bonpland recrossed the Andes and reached the Pacific, spending two months in Lima before boarding a ship to Guayaquil and then Mexico. As Humboldt sailed north, he made the fi rst measurements of the temperature and speed of the massive ocean current that now bears his name.

Sweeping north along the west coast of South America, the Humboldt Current brings cold waters from Antarctica that help keep the coasts of Peru and Chile cool and dry. The nutrient-rich flow also supports the largest and most productive fi sheries on the planet, accounting for an estimated 12 percent of total world catch. Most of this consists of the anchoveta, a kind of anchovy that is the cornerstone of Peru’s industrial fishing industry.

This rich ecosystem is threatened by coastal development, overfishing and pollution. Every few years the El Niño climate phenomenon brings an influx of warm water that can disrupt marine ecosystems and the birds and mammals that depend on them, including Humboldt penguins.

In Peru, the Conservancy is working with the government and other partners to promote the creation of coastal marine reserves and improve fisheries management. In just the past five years, three reserves have been created. “The Conservancy’s success in improving the management practices [here] can be a tipping point for fi sheries management worldwide,” says Conservancy project manager Fernando Ghersi.

It took Humboldt another year and a half to make it home. He made a transect through Mexico and a stop in the United States. He dined at the White House as a guest of Thomas Jefferson, who—inspired in part by news of Humboldt’s discoveries—had just dispatched Lewis and Clark on their journey.

When the scientists landed in France on August 1, 1804, Humboldt found that his travels had made him one of the most famous men in the world. He spent the rest of his life analyzing and writing up his findings in dozens of books and papers.

When Humboldt died in 1859, the New York Herald called him “one of the greatest men of his age or of any other.” He popularized natural science as no one ever had before. Ironically, despite the hundreds of places, species, schools and natural features named after him, Humboldt has been largely forgotten today. But his essential insight is as relevant as ever: that only by combining detailed observations with big-picture thinking will we ever be able to grasp the fundamental unity of the natural world, including our place in it.

And the best way to do this, he knew better than most, is by experiencing the world firsthand—whether by visiting a neighborhood park or a distant snow-clad volcano. “The most dangerous worldview,” Humboldt wrote, “is the worldview of those who have not viewed the world.”