Kim Schonek stands at the edge of the barley field, keeping a wary eye out for a rattlesnake she saw nearby the other day. The soft, green barley stands chest-high, swaying in the warm winds of the Verde Valley. In another week, it'll begin to dry out under the June Arizona sun.

“Soon it’ll be amber waves of grain,” she says with a smirk. Everyone makes that joke around here, in the small town of Camp Verde. Barley, in this region full of alfalfa and field corn, has lately become the talk of the town.

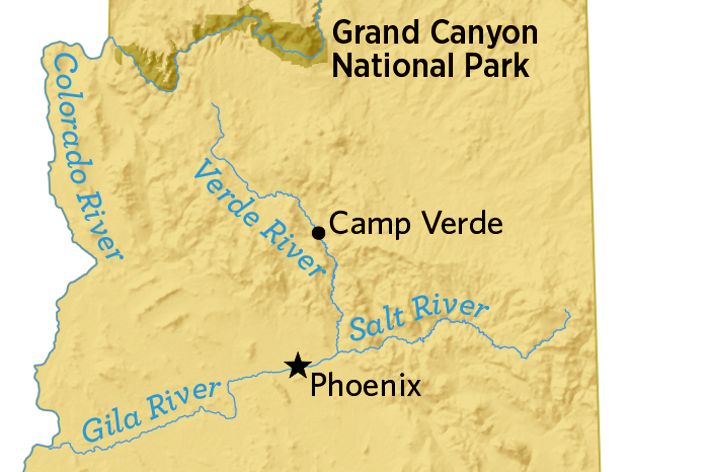

Camp Verde sits in the middle of the Verde Valley of Arizona, a semi-arid stretch of farmland, vineyards and horse country north of Phoenix and south of Flagstaff and the Grand Canyon. Its lifeblood, the 190-mile Verde River, cuts a lush path through the desert valley on its way to meet the Salt River, which in turn provides a portion of the drinking water to fast-growing Phoenix.

The Verde is a gem in a state famous for its deserts: a designated Wild and Scenic River for more than 40 miles. Razorback suckers and Colorado pikeminnow, both endangered fish, swim here in rippling water shaded by cottonwoods and willows. It’s one of the last rivers in Arizona that still runs year-round—except lately, sometimes, it doesn’t.

Seven major irrigation canals—“ditches” to locals—divert water from the river to farms, ranches and, increasingly, residential lawns. But irrigation combined with drought, a growing population and the proliferation of groundwater wells has become too much: The Verde has run dry in some stretches in recent years, putting fish and farms alike at risk.

Planting Barley to Save the River

Schonek, a program director for The Nature Conservancy, set up shop in Camp Verde in 2008 to find ways for the farmers and residents of the Verde Valley to keep the river flowing. What’s happening here in the valley is a microcosm of the issues communities are facing throughout the parched Colorado River basin: the struggle to grow economically and build new industries, but also maintain the family farming and ranching cultures that have existed for generations—and to do so amid the constraints of an increasingly stressed water supply.

In Camp Verde, at Schonek’s urging, an unlikely band of farmers, conservationists and local entrepreneurs is betting on barley as a way to thread this needle.

For three years the biggest farm company in town, the family-run Hauser & Hauser Farms, has been planting barley instead of alfalfa or field corn in a section of its fields. The barley, meant for beer-making, uses about one acre-foot of water per year, compared with corn’s two acre-feet and alfalfa’s four. And barley needs the water not in high summer but in the spring, when the Verde River is running fast and deep.

But for this crop-switching experiment to succeed and spread, the farmers need someone willing to malt the barley, and then someone willing to buy the barley and brew the beer. It’s a big bet and the stakes are high. Anyone could back out and the house of cards will collapse. But Schonek, standing on the edge of that fresh, promising barley field, is confident.

“Everybody’s taking risks,” she says. “And we have a lot of trust in each other.” That might be enough.

Claudia Hauser speeds past one of her cornfields and a row of pecan saplings in a utility vehicle. She’s wearing a baseball cap with the logo “FarmHer” on it, on her way to check a ditch headgate—a metal slat that controls how much water flows from the river to the farm.

Hauser and her husband, Kevin, have run Hauser & Hauser Farms for decades. They met as kids and knew each other as teens. She was shy, afraid to walk to the bus stop alone, she says. Kevin was a local farm boy skipping class who offered her a ride. They met again years later and have farmed together ever since, she says, and they’re anxious to ensure their children can continue farming in Camp Verde.

The Hausers first got to know TNC more than a decade ago, when they began working together on water conservation projects. In 2016 they completed a conservation easement together. The agreement ensured the land would not be subdivided, reducing the property’s tax value and easing the financial pressure on the family, Hauser says.

“Row croppers don’t make a lot of money,” she says. “But now, we’re good.” Today, the Hausers grow a variety of crops, including sweet corn—their specialty—plus field corn, alfalfa and, lately, barley.

Hauser pulls up to the ditch gate. It looks like a tiny dam, channeling water down small concrete chutes that carry it to retention ponds and little canals along the cornfields. Such ditches crisscross the Verde Valley and have since the 1860s.

Quote

Claudia Hauser wants to make sure her farm lasts forever. To do that, she says, they need the Verde to keep flowing.

Hauser pulls out her phone and—through controls on her screen—adjusts the amount of water flowing into the farm’s retention ponds. “This … is a game changer,” she says, nodding at the phone. Previously, she had to walk through the fields at 2 a.m. to turn a rusty wheel to adjust the water. The automation is one of many water-saving experiments on the farm as part of the collaboration with Schonek and TNC.

So when Schonek came to the Hausers in 2016 with another idea—plant barley instead of alfalfa or field corn—the Hausers didn’t immediately laugh her off. “For a farmer who has land payments and equipment payments, you want to plant what’s going to get you the best money,” Hauser says. A new crop is a risk, especially one without an established market in the region.

To lessen the risk, TNC guaranteed a certain price for the first crop of barley. That convinced the Hausers. “We couldn’t lose,” Claudia Hauser says. “I mean, we could just do alfalfa and field corn, but where’s the fun in that?”

In 2017, the Hausers planted a pilot barley crop on 14 acres. The next year they planted 144 acres. In 2019, they planted the most productive 120 acres and still harvested more barley than in 2018.

Hauser hopes it helps the river. The lack of water is always in the back of a farmer’s mind, she says. “We need to make sure that the life of our farm is forever.” To do that, she says, they need the Verde to keep flowing.

Where the Water in the Verde River Goes

The Verde River first burbles up from the ground near Paulden, Arizona, northwest of Camp Verde. On most days the river here is a trickle through the small canyon it has cut in the dry valley. Nearby, prairie dogs pop up from their holes and a pronghorn lingers near the ruins of an old duck-hunting lodge. A few miles downstream, the river runs through a wide canyon, past a boulder covered with petroglyphs.

The Verde watershed, and most of Arizona, is part of the Colorado River basin—a stretch of land across seven U.S. and two Mexican states that drains into the Colorado. Today, the river rarely makes it to its mouth at the Gulf of California. More water has been allocated to farmers and other users than actually exists in its main stem most years.

The whole basin, says Aaron Derwingson, who works on water projects in the basin for TNC, is now facing a “perfect storm”: Over-allocation, long-term drought and a higher demand for water have come to a head. And it’s not just the water in the river that matters. Farmers and residents have turned to pumping groundwater, which in turn affects spring-fed tributaries. “All water is connected in the basin,” he says.

This dynamic is apparent in the Verde Valley. Agriculture uses a large portion of surface water, as it has for decades. Meanwhile, the number of groundwater wells in the valley has grown from 250 in 1950 to more than 8,900 today.

What is true for the Verde is true across the Colorado basin: As wells suck water out of the ground, and ranching and agricultural producers continue to pull away surface water, the rivers sometimes don’t flow—and the farmers and cities using river water may have to turn elsewhere.

How River Conservation Supports Local Businesses

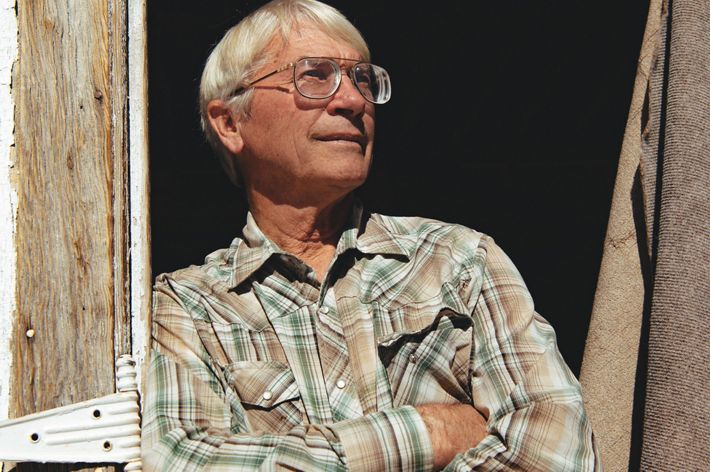

Chip Norton is poring over spreadsheets in a nondescript warehouse full of room-height silver vats and bags of grain in Camp Verde. He’d rather be kayaking on the Verde River with a beer in hand. “I love to go paddle in the Verde River in the summer,” he says. “When there’s enough water to float a boat.”

Norton began volunteering with TNC after retiring a decade ago, removing invasive plants from the Verde riverfront. He was a rock climber and a rafting guide. When he and his wife decided to stop rock climbing, he says, “we retired to running marathons.”

Still, Norton was itching for a new project. When he told his friend Schonek over a beer that he was considering opening a brewery, she told him she had been mulling an idea of her own: getting farmers to plant less-thirsty grains like barley instead of corn and alfalfa. Could they put their ideas together?

Barley is a key ingredient in beer, along with hops and water. But to be usable to a brewer, harvested barley must be malted—a process that essentially prepares the grain for fermentation and makes it taste a bit nuttier. And to a craft brewer, barley grown and malted nearby is both appealing for its marketability and for its reduced transportation costs. But there was no malt house in Arizona.

Quote

This year, craft brewers within a 100-mile radius of Sinagua Malt are buying all the barley Norton has.

After more brainstorming, Schonek and Norton had landed on their answer: What about a malt house?

Norton ran with it. He established Sinagua Malt as a public benefit company in 2017 to process the grain coming from Camp Verde, using his own savings and investment from TNC to build the business. He now runs the malt house pro bono out of a warehouse near the I-17 exit to Camp Verde. The sign outside still reads Vince’s Auto-Body from the last owner.

Today Norton is rushing. He and his assistants have to finish processing last year’s barley before this year’s is harvested in two weeks. The malt house is operating at max capacity. The demand is there to operate the malt house at four times its current output, he says. He’d like to at least double it in 2020. This year, craft brewers within a 100-mile radius of Sinagua Malt are buying all the barley he has.

It’s a sunny Thursday in June at Arizona Wilderness Brewing Company in downtown Phoenix. The misters on the patio—which use recycled water—have just kicked on and the two founders, Jonathan Buford and Patrick Ware, are lounging underneath the spray, chatting with Kim Schonek about bringing their beer to an upcoming event to support sustainable rivers.

The brewing company has bought the bulk of the malted barley produced by the Hausers and Norton: In 2018, when the Hausers planted 144 acres of barley, the crop produced more than 253,000 pints of beer. In 2019 it produced more than 1 million pints.

Arizona Wilderness pays more for the grain than the going rate charged by larger commercial producers. But the founders say sustainability and the distinct taste of the barley are integral to their brand.

The two look like relatives of the guitarists for ZZ Top, with long beards and sunglasses. They opened the brewery in 2013 in Gilbert, Arizona, and in 2019 opened this downtown Phoenix location. Nearly all of their business—like most of their ingredients—is local.

Schonek holds up a four-pack she wants to buy. A few days ago, Claudia Hauser sampled the beer, a watermelon gose made from watermelons her son grew, and loved it. Schonek wants to buy more to give out around town. Preaching crop-switching to save a river might go down a little more smoothly with a cold one.

She’s making some headway. On nearby Yavapai-Apache Nation lands, the Yavapai have planted an heirloom variety of rye. Called gazelle rye, it uses water earlier in the growing season than field corn, just like barley. Artisanal bakers prize it for its distinct flavor.

Meanwhile, Derwingson’s team is launching a similar venture in Colorado, this time focused on switching an irrigated pasture to a heritage variety of apple. Crop-switching, Derwingson says, will never be a silver-bullet solution to all water woes in the Colorado River basin, but it will become one of the options TNC suggests as communities come to grips with their stressed water supplies.

Back on the patio at the brewery, the ever-practical Schonek keeps up a running conversation about what happens next: Will the harvest happen on time? Will the rains come? Will the combines work as they should? Will the Verde run dry this year?

In 2018, the crop-switching project reduced water demand on the Verde River by 78.5 million gallons. If all goes as planned, they’ll save that much again every year the malt house is in operation.

Quote

Preaching crop-switching to save a river might go down a little more smoothly with a cold one.

The coming year also will test the young project: For the first time, TNC won’t guarantee the price of the barley. If the Hausers plant the crop and Norton processes it and brewers buy it—and everyone makes money—Schonek will know the project is financially viable.

“There were some moments where this whole thing could have fallen apart. And it would have been terrible,” Schonek says. “But we’ve passed the point where, I don’t know if this will feel as wildly successful 10 years from now [as it does now], but I know that it will be something.”

By the second week of June in Camp Verde the barley has begun to brown and the sun is beating down hard on the valley.

Chip Norton, not an entirely failed retiree, has taken a break from the warehouse to head down to the river. At the water’s edge he cracks open a can of beer and tucks it into his life vest, just under his chin.

Two dogs and a child are playing in the river as a mother looks on. Norton waves and drags his kayak into the Verde.

Norton wanted a retirement project but ended up with a company. He wanted to kayak this river year-round, and he ended up running a malt house.

Downriver he navigates a few rapids before the sun begins to set. Bats emerge from their sleep, searching for insects above the water, the whip of their wings so close that little puffs of air can be felt when they pass. A river otter bumps Norton’s boat and surfaces next to him. Norton laughs, lifts the beer from his vest and takes a sip.

Editor’s Note: As we went to press, Kevin Hauser passed away, at home with his family. He is a vital part of the Verde River story, and we honor his memory.