A Periodic Cycle The emergence of periodical cicadas is one of nature’s great annual events, and it’s a boon to many other species of animals that feast on the slow-moving insects. © David Gumbart/TNC

All about Cicadas

Want more answers? Jump to more on:

An inescapable screeching sound coming from nearly every nearby tree and local forest. Winged insects clinging to unsuspecting people—or colliding with them, as the big bugs haphazardly fly around.

If these scenarios trigger a memory, you may live in a region of the United States that is home to periodical cicadas. The sudden appearance of millions of screaming, red-eyed insects is not something that is easily forgotten.

The periodical cicada spends the vast majority of its life underground, emerging after 13 or 17 years (depending on the species) to transform, reproduce and ultimately die over the space of just a few days. Huge populations of these insects—numbering in the millions—have synced up to emerge within the same window of time to give them the best chance of successfully finding a mate and producing young before they are eaten by predators or expire naturally.

13 states can expect to see the Brood XIV 17-year cicadas this spring, including Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. Kentucky and Tennessee will likely get the most cicadas this year.

Once this generation of insects—and the sound of their mating call—has died away, cicadaphiles may still be able to spot their offspring, which will begin hatching in early August. Check around tree roots where you may see nymphs crawling back into the ground to begin the cycle anew.

If you miss this year's hubbub, your next opportunity will be in 2027, as Brood XXII 13-year cicadas emerge in parts of northeastern Louisiana and southwestern Mississippi.

Quote: Tamra Reall

It’s magical, and that’s part of their name. Their genus name is magicada, and it’s because it’s a magical experience.

Once the soil reaches about 64 degrees Fahrenheit at a depth of 12-18 inches, the emergence of the cicadas is triggered. Male cicadas emerge first, followed by females a few days later. Females can be identified by their pointed abdomen and sheathed ovipositor, the organ they use to lay eggs.

As they leave the ground, the cicadas will shed their shells and develop wings, allowing them to fly around and locate fresh hardwood trees and shrubs. You can see the singing organ of the male cicada by gently raising its wing and looking for the tymbal located where the wing meets the body. Above ground, cicadas have no natural inclination to fly away from predators, which is why they don’t seem to be afraid of people.

After they’ve found a tree or shrub to land on, the cicadas will mate and lay eggs at the end of branches. Newly hatched cicadas will then chew through the branch tips, causing them to fall off, carrying the young insects back down to the soil where they will spend the next 13 or 17 years.

Bio-diversify your inbox.

Get the latest nature news (and occasional bug photos) monthly. Check out a sample Nature News email.

How Humans Impact Cicadas’ Natural Cycles

This is one of nature’s great cyclical events, and it’s a boon to many other species of animals that feast on the slow-moving insects. Like so many other natural cycles though, factors like ongoing human development and climate change could have a significant impact on an emerging brood. Scientists are eager to see how many of the cicadas will make an appearance this year compared to previous generations.

There has been increasing evidence of cicadas emerging several years ahead of schedule, which some scientists have suggested may be due to shifting temperatures. At the same time, insect populations have also seen serious declines worldwide over the last few decades, but the causes of these drops are not yet fully understood.

You Can Help! Cicada Community Science

That makes it more important than ever for scientists to learn where cicadas are emerging and in what sort of numbers—and we can all help. Using phone apps like Cicada Safari and iNaturalist, you can make digital observations that use your phone’s GPS to populate a map, helping to determine if or how a current year's brood range may have shifted since they last appeared.

As loud as they may be, we have plenty of reasons to be happy that cicadas will show up in huge numbers this year.

Cicada FAQ

Answers to common questions about periodical—and other—cicadas.

-

Where do cicadas live?

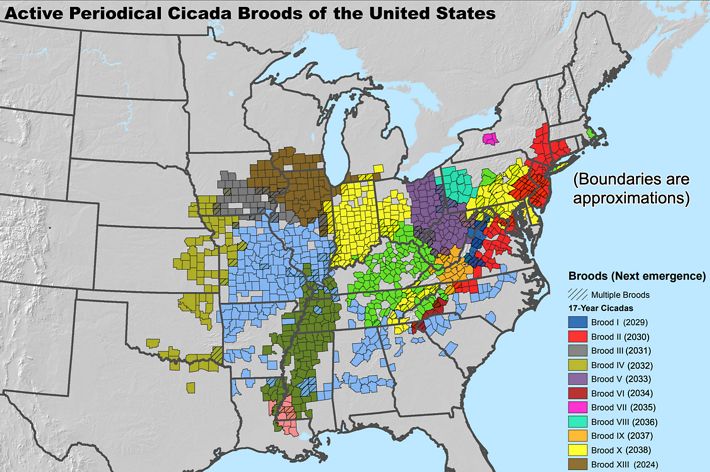

Seven species of the genus Magicicada can be found in eastern North America, emerging in two 13-year broods and twelve 17-year broods across parts of New England and the mid-Atlantic, reaching through the south into the Gulf coast states and parts of Texas and extending north within the Mississippi River basin into southern Wisconsin. Two broods, XI in New England and XXI with an historical range in the Florida panhandle, are believed to be extinct.

-

Why are cicadas so loud?

The extremely loud noises you hear are the mating calls of male cicadas. To humans, it might sound obnoxious or unpleasant, but it’s actually an important way for cicadas to find each other in order to reproduce within a relatively short amount of time. There are five basic sounds to a ciacada’s call: chorus, three stages of courtship calls and female wing flicks. The calls can reach 80-100 decibels in volume—equal to the sound of a garbage disposal, lawn mower or a jackhammer.

-

Do other animals eat cicadas?

The cicada emergence is hugely beneficial for other animals. Many animal species time their own reproduction with the cicadas, allowing them to feed even more of their young successfully than they might otherwise. Scientists can actually trace increases in other animal populations to the appearance of cicadas.

Living with Cicadas: Embrace the Emergence

With cicadas all around, you might be wondering how they will affect your pets, plants or yard. The good news is that cicadas are harmless on all counts.

Any damage that may be caused to mature trees and shrubs by hatching larvae should be minor and temporary. However, it’s probably a good idea to delay planting new trees until the fall.

If you’re worried about damage to an ornamental shrub or fruit producing tree, the best course of action is to cover it with netting while the cicadas are out (net holes should be 1 cm or smaller). Be sure to attach the netting to the trunk or the cicadas will climb up the trunk to the branches. Spraying the tree with chemicals won’t stop the cicadas but may poison the animals that eventually eat them.

You may notice patches of your yard where chunks of sod have been removed and small holes have been dug. You are probably looking at evidence of foxes, raccoons, skunks and crows on the hunt for cicada nymphs and a high-protein snack.

How to Live with Cicadas

Wondering how cicadas may affect you, your pets, plants or yard? We have answers.

-

Why did a cicada land on me?!?!

If a cicada lands on you, it’s by accident. Cicadas fly around looking for hardwood trees or woody shrubs to land on, where they hope to attract a mate and lay their eggs. In places like cities, there are often more people than trees and the cicadas might have to spend some time flying around to find the right spot.

-

Can cicadas hurt me?

Cicadas do not bite or sting. Their mouths have no mandibles, or jaws, and they have no physical characteristics like a stinger with which to defend themselves. They may emit an ear-piercing screech, however! The feeling of a cicada gripping you with their feet might be a bit strange or surprising if you’ve never had one land on you before. After all, they’ve evolved those feet to grip onto tree bark, not humans.

-

Are cicadas poisonous? Are my pets at risk?

Cicadas are not poisonous. Dogs and cats are among the many animals that seem to love eating cicadas, but thankfully the insects alone don’t pose any risk to them. Unless of course they eat too many cicadas, which—like too much of anything—could make them sick.

-

Can people eat cicadas?

Yes, humans can eat cicadas too. As with many other types of insects, adventurous humans can find recipes to try out with cicadas as well. HOWEVER, it’s also important to note that cicadas that have been living under lawns treated with pesticides might still have trace amounts in their bodies. "Organic” cicadas are more likely to be found in parks or other areas free from chemical treatment.

-

Will cicadas harm my plants?

Cicadas do not eat garden plants, so gardeners don’t need to worry about them destroying all their hard work like a swarm of locusts or invasive Japanese beetles might. In fact, cicadas don’t really eat at all, but will use their mouthparts to sip sap from trees and stay hydrated.

-

Will cicadas harm my trees?

Cicadas will not kill mature trees and shrubs they lay their eggs on. Any damage that may be caused by hatching larvae should be minor and temporary. Still, if you’re worried about damage, the best course of action is to cover your trees with netting. Spraying the tree with chemicals won’t stop the cicadas but may poison the animals that eventually eat them.

-

Will cicadas harm my lawn or yard?

In the short term, cicadas will alter your lawn’s appearance, but in the long term it will actually help. All those tunnels cicadas are digging as they emerge will aerate your soil and encourage root growth this fall and next spring. While your yard may appear to be a mess from all the holes and mud chimneys, just run a rake over your turf and add some grass seed after the cicadas are gone and your yard will be as good as new in no time.

-

How long do cicadas last?

Cicadas that emerged in May will begin to die off in mid-June after they have mated and laid eggs. The eggs will begin to hatch in early August. The dead adult insects will drop back to the ground and help fertilize the soil. You can even add dead cicadas to your compost pile. It’s a great example of the natural circle of life.

A Blast from the Past: 2008

It’s been 17 years since Brood XIV last emerged. What was happening in 2008?

- Barack Obama was elected to become the 44th President of the United States.

- NASA's uncrewed Phoenix spacecraft confirmed the presence of water ice on Mars.

- Iron Man was released in movie theaters, kicking off the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU).

- Taylor Swift received her first Grammy nomination (for Best New Artist—Amy Winehouse took home the award).

- Satoshi Nakamoto published Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.

- Adorbs, hate-watch and Me Too entered the lexicon.

- Beijing, China hosted the Summer Olympics. Jamaica's Usain Bolt shattered speed records in the 100- and 200-meter dashes; USA's Michael Phelps surpassed Mark Spitz's medal record, winning eight gold medals; and Rohullah Nikpai earned Afghanistan's first ever Olympic medal with a win over world champion Juan Antonio Ramos of Spain for a bronze in taekwondo (58kg).