From Overgrowth to Renewal

How restoration is transforming western dry forests

Written by Liane O'Neill | Illustrations by Erica Simek Sloniker

It’s a sunny day when the whirring of a blade sounds through the forest. A large machine called a feller buncher grips the trunk of a Douglas-fir that’s been identified for removal. Guided by a restoration plan that’s been years in the making, the operator steers around a nearby ponderosa pine and cuts the Douglas-fir before moving it to a bundle of other trees. Then, with the sounds of jingling and crunching, the freshly cut trees are pulled out of the woods to another machine that knocks off their branches, shaping them into logs.

Over the next few weeks, crews of chainsaws follow. Trained experts work around the healthy ponderosas and Douglas-firs that remain. They cut branches that extend close to the ground and thin congested groups of slender saplings, placing the cut trees into piles that will be burned, once they have dried in a year’s time.

Keep In Touch

Sign up for monthly emails to discover news, updates and opportunities.

Under the careful tending of these stewards, a forest that was once matted with a dense understory of branches, stunted trees and anemic shrubs opens up once more. It sighs as sunlight warms the ground, and breezes shift the branches of trees no longer constrained by crowding.

Quiet returns. Grasses and forbs germinate, taking advantage of the sunlight and moisture that can now reach the forest floor. Soil layers build up as scattered branches and needles accumulate and break down.

Two to five years after the original thinning, flames bring crackling heat. Trained teams holding heavy drip torches disperse to ignite dried and dead wood and debris. Following a burn plan, they coax the fire forward, all the while monitoring its progress and the weather to ensure it stays within defined perimeters.

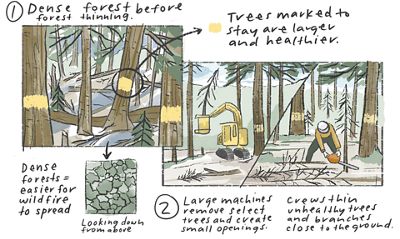

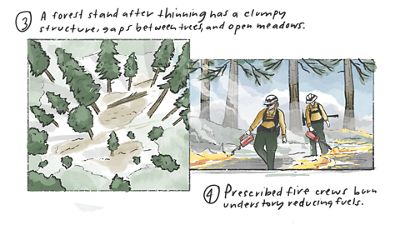

In a dense forest prior to forest thinning, where it is easier for wildfire to spread, trees marked to stay are larger and healthier. Then, large machines remove select trees and create small openings, and crews thin unhealthy trees and branches close to the ground.

A forest stand after thinning has a clumpy structure, gaps between trees, and open meadows. Prescribed fire crews then burn understory, reducing fuels.

A FOREST MADE FOR FIRE

The fire burns close to the ground at low heat with short flames. It consumes deep needle litter and dried vegetation, removing excess fuel that, under the wrong conditions, could stoke a destructive blaze.

According to Mike Schaedel, Western Montana forest restoration director with The Nature Conservancy, dry forest ecosystems like these, which grow across 150 million acres of western North America, have evolved to depend on fire. For example, seeds from ponderosa pine and western larch use the bare soil created by burns to germinate.

“If fire wasn’t important in these landscapes, that wouldn’t be an adaptation,” Schaedel says.

Western dry forests have had a close relationship with fire over millennia.

When European settlers came to western North America, they found park-like dry forest landscapes—grand giants spaced apart with grasses underneath.

“That wasn’t an accident,” Schaedel says. “People have been using fire to carefully maintain those forests for generations, using their own traditional ecological knowledge and science.”

Western dry forests became dependent on flames, which cleared excess growth and brought about life and regeneration. But today these ecosystems have become overgrown -- the result of forest and fire management practices that over-harvested large trees and removed fire from the landscape by preventing Indigenous burning and mandating any fires be rapidly put out. As a result, wildfires are now behaving in unpredictable ways and burning larger swaths of forest at greater severity.

This graphic shows ponderosa pine fire adaptations. It notes cambium protected from heat, and thick, fire resistant bark, as well as long needles that create a fluffy layer conducive to carrying fire. Low intensity fires then prune the trees, limiting ladder fuel for high-intensity fires. Additionally, fire clears the ground, enabling seed germination.

How Photography Teaches Us Restoration Lessons

Photography is a powerful tool to understand the efficacy of forest health treatments. In our new article, learn how photographer John Marshall's camera is helping uncover the legacy of fire suppression across the West while also showing us what the next chapter could be. Read more.

RESTORING HEALTHIER FORESTS

Together, ecological thinning and burning can transform a forest’s trajectory and return the land to a healthier, more resilient condition. Studies have shown burning alone can reduce wildfire severity in dry forests by up to 62%. When burning is used in combination with thinning, that number increases to 72%.

TNC experts and partners work with landowners to identify dense sections of forest for treatment. They focus on landscapes where high-severity fire could pose the greatest risk—areas near communities or important ecological resources, like large trees, old-growth forests or threatened wildlife habitat.

They aim to restore a forest structure with greater resilience to severe wildfire and climate change, one that mimics conditions from hundreds of years ago, when low-intensity fire regularly managed forests.

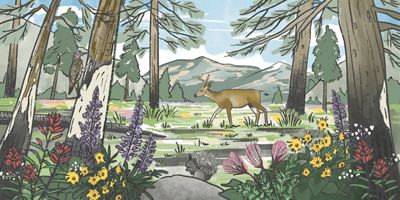

When thinning, experts try to achieve a clumpy spatial pattern, in which some trees are grouped together while others are individually spaced and broken up by meadows and gaps. Fire-adapted species, like ponderosa pine and Western larch, as well as the biggest, healthiest trees, are left to flourish, along with some younger trees, creating a diverse forest structure.

“We want to see a wide range of tree sizes and ages—old intermixed with young, and even some dead trees, for the benefit of wildlife,” says Rob Addington, TNC’s Colorado forest and fire program director. “And we want to see meadows interspersed throughout the forest—in some cases, some pretty large meadows with vibrant plant communities.”

In many ways, restoration begins not with the forest canopy, but with the forest floor. Prescribed burns and other low-intensity fires help recycle nutrients, spurring regrowth.

Quote: Matthew Ward

Generally, low-intensity fire has a positive impact. You’re speeding up the process of nitrogen being reincorporated into the soil. That nitrogen comes from decaying needles, leaves and woody debris.

Addington says that often the goal of restoration is to open up the forest and stimulate the grasses, forbs and other plants that make up ground cover. This, in turn, encourages greater diversity, supporting a more resilient ecosystem.

“A lot of diversity originates in the ground cover and the understory plant community,” he says. “The diversity there affects the diversity of the insect community, which can then affect the diversity of other wildlife, like the songbird population. You get these trophic cascades that go all the way through the system.”

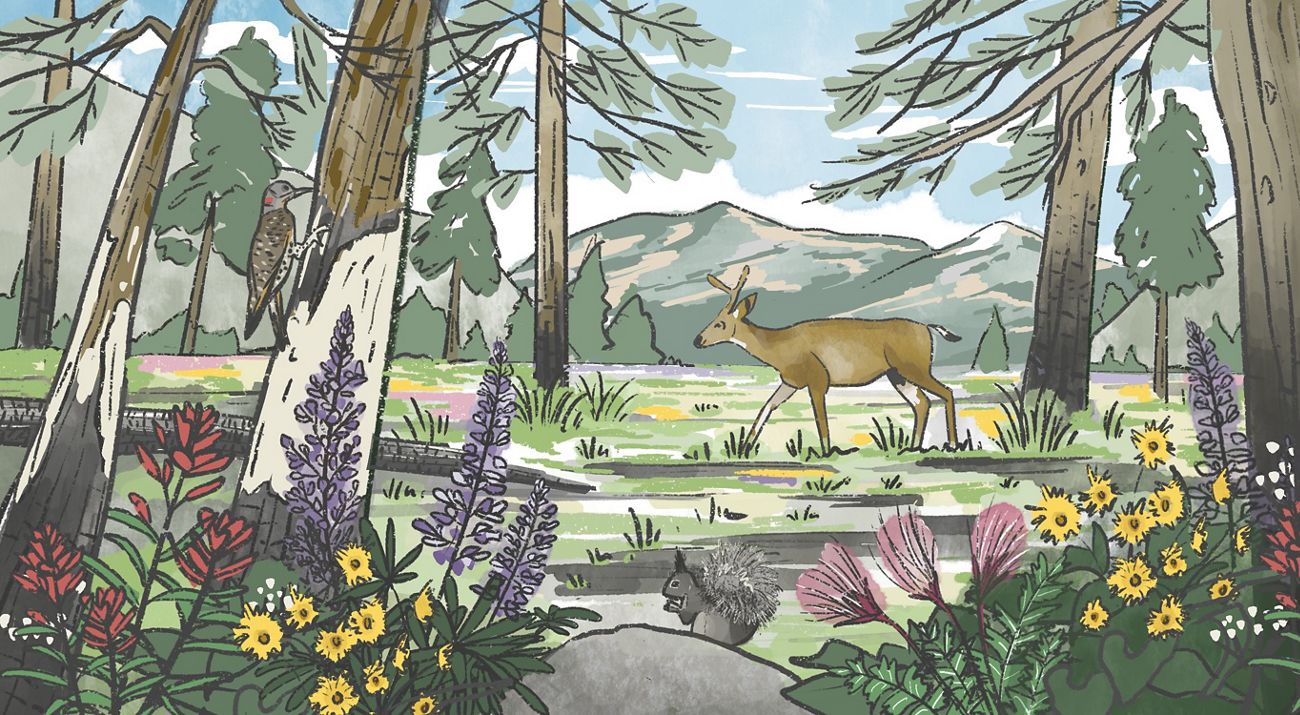

SPRING OF REGENERATION

Just months after a prescribed burn, the forest is already transforming. Out of the soot and scorch, below the healthy, newly spaced conifers, young grasses, forbs and sedges emerge, and recovery begins.

In the spring, lupine send knee-high blooms of purple and blue up into the air, mingling with yellow splashes of sunflower-like balsamroot and arnica, as well as multicolored hues of paintbrush flowers. In forests with wetter meadows, violet and lilac tones of blue camas, a culturally significant food for Indigenous Peoples, dot open spaces.

“Following either thinning or burning, it often doesn’t look great, but when you return a few months later or less, what you see in terms of what's coming back is really astounding,” Addington says.

By the beginning of summer, grasses and shrubs like mountain mahogany, wax currant and antelope bitterbrush are putting out healthy shoots and branches.

The verdant growth and new openings in the forest created by the restoration attract mule deer and elk, who seek out the nutrient-rich plants. Birds, like hairy woodpeckers, northern goshawk and Mexican spotted owls are also attracted to burn sites.

“A lot of birds key into fires—whether it’s a woodpecker that’s going to search for insects after fire, or whether it’s a hawk zooming over because there’s nothing for mice or voles to hide in,” Ward says. “They’ll start hunting at those locations, hoping for a high success rate. So wildlife return almost immediately.”

In Montana, dusky grouse, large fowl with dark feathers and purple-red air sacks on their necks, emerge to mate.

“They seem to just pop out of the woodwork, I’ve seen it a couple of times now in stands we’ve thinned and burned,” Schaedel says.

THE CYCLE OF RESTORATION

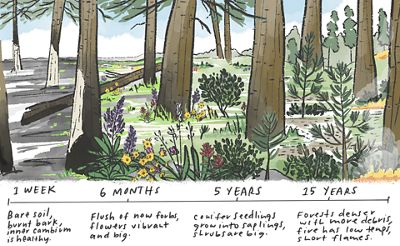

The flush of new life and regrowth of vibrant flowers and understory plants lasts about two to three years. In a few years, seedlings from fire-adapted trees like ponderosa pine, germinated by soils exposed by the return of fire, will emerge.

In five years, those seedlings will develop into saplings. Shrubs will grow large and robust, and hearty grasses will continue to develop.

As the years roll on, dried vegetation will begin to accumulate once more, as branches shed, trees live and die, and needles begin to pile. Some of the young saplings will begin to crowd the more mature trees.

“As you get further away from when that fire happened, the cycle starts again where you see more trees coming in,” Ward says. “And then over time, you’re going to see this reduced diversity and reduced use by wildlife.”

After one week, the forest has bare soil, burnt bark, and healthy inner cambium. After about six months, the forest is flush with new forbs and flowers vibrant and big. After about five years, conifer seedlings grow into saplings and shrubs are big. After about 15 years, the forest is denser with more debris, and fire has low temperatures with short flames.

Experts are finding that forests need to be burned about every 15 years to restart this cycle and remain healthy.

On some sites, fire may occur on its own even earlier. And when that happens, in areas that have been thinned and burned, the fire will drop out of the canopy, down to the ground, where it will likely burn low, without inflicting significant damage on the large, older trees.

And the cycle continues. The understory plants and wildlife return, the site matures and low-intensity fire returns in some shape or form. Over and over again.

“I always look at restoration as a process or a journey, not an event,” Addington says. “You’re continually improving and continually increasing the health and the resilience of the system.”

Humans have always been critical to maintaining that cycle, which in turn reduces severe fire risk and protects important ecological, social and economic resources.

“Everything gets disturbed,” Ward says. “And that's how the system evolved. Humans are now a disturbance, and we are part of the restoration effort.”

TNC’s Western Dry Forests Program leads and convenes efforts to restore forest resilience and reduce the severity of wildfires across the West. Learn more about how we’re partnering with state programs and other partners to restore dry forest ecosystems.

The forests we depend on, depend on us

Continue learning about The Nature Conservancy’s Western Dry Forests Program.