What the Camera Sees in the Trees

Before-and-after photos show how Washington forests are reborn.

Dustin Solberg, Writer/Editor

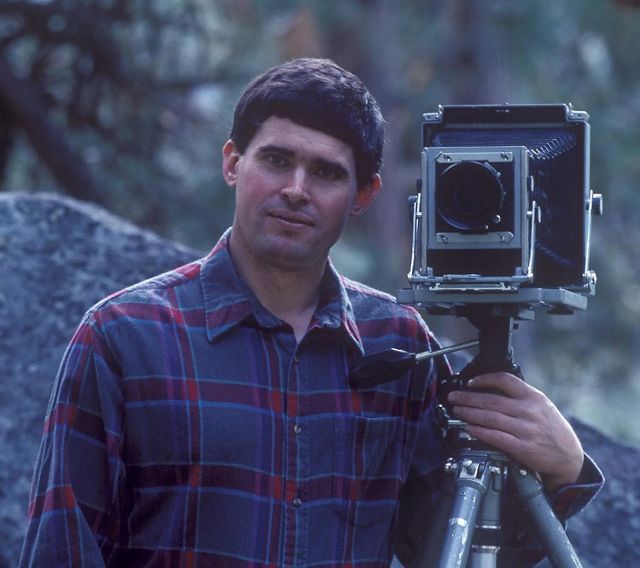

John Marshall knows how to take beautiful photographs. He’s built a career on it. His photos of pure natural splendor—old-growth forests and alpine lakes and volcanic peaks and more—dazzle anyone who’s ever flipped through his work in National Geographic magazine or one of his sensational coffee table books.

Then, some years into his professional life, Marshall, who trained as a biologist, began to wonder: Could his acclaimed photography do something more?

"I was taking pictures to have an emotional impact,” he says, and that’s what they did. “But I always felt like I had more to offer.”

That itch lingered, even as he kept on capturing scenic wonder wherever he went. When the kids were off at school, he went to work in beautiful locales. Yet looking around in the places where he set up his camera and tripod, he often could see something else was going on in the lands around him.

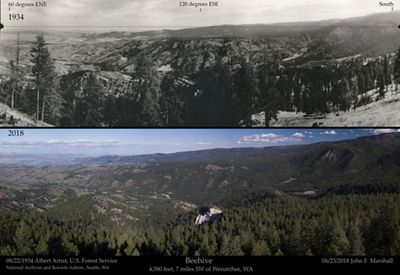

Forests were changing, and the cause was clear: Forest fires had been kept out, suppressed, extinguished at the first opportunity. It was happening all across the Western United States, and had been for up to a century or more. It meant that the relatively open and easily walkable forests of the past are, unlikely as it may seem, now crowded with too many trees. In some places, there were now too many trees to allow for an easy stroll through the forest. He wanted to show what was happening, yet a single image could only tell so much. He needed a way to tell the rest of the story.

Then he learned that, in a sense, the U.S. Forest Service already had the rest of the story. It was in the form of a carefully executed set of 1930s-era black-and-white photos from all across the Pacific Northwest and securely preserved in the National Archives at Seattle. It turned out that a forest scientist wanted Marshall’s help to show how today’s forests didn’t at all look like the forests captured in those black-and-white photos.

Before long, Marshall was hiking forest trails to capture current-day photographs of sites documented in the Forest Service Osborne series—so named for forester William B. Osborne, who designed the specialized and rather peculiar camera, called the Photo Recording Transit No. 6, designed for the original project.

For Marshall, it was the something more he’d been looking for.

Once his images were paired with those original photographs, he had a clear takeaway: Fire has always been part of a forest’s natural cycle. Take it away—by putting out naturally occurring, lightning-caused fires and unjustly snuffing out the tradition of cultural burning by Indigenous Peoples in North America—and forests are guaranteed to change.

But it’s not a change for the better. It comes with consequences: like the threat of increasingly catastrophic wildfires, vulnerable drinking water supplies and seasons when the air can be unsafe to breathe. A warming climate brought on by the burning of fossil fuels makes the risks that much worse.

“We caused the forest to morph into something it never was,” Marshall says.

The Future Forest at Cle Elum Ridge

Just as Marshall’s camera uncovered a damaging episode in the history of our forests, it’s also showing what the next chapter could be. Today, Marshall is helping The Nature Conservancy restore forests—on former industrial timberlands—by photographing before-and-after shots of what the forest was, and what it can become once again.

Restoration Transformation

Similar to the forests of Cle Elum Ridge, restoration in dry forests across the west is helping initiate a cycle that enables dry forest ecosystems to recover and become healthier and more resilient in just months. Check out our article.

“We like to say we have a tree problem,” says Kyle Smith, TNC Washington’s director of forest conservation and management. “For the last hundred-plus years, fire in these forests has been suppressed, and it’s caused these forests to become really dense. When a fire comes through, it’ll go up into small trees and climb up into the crowns of the larger trees, killing them.”

TNC began restoring areas of the 9,700-acre Cle Elum Ridge forest 10 years ago. Today, the forest is a working laboratory of forest restoration—a place of experimentation, demonstration and learning.

Again, Marshall’s camera is helping to tell a story—but this time, it’s a story about restoring the forest.

Over the years, his tools have changed. Today, instead of lugging around a tall 3-legged orchardist’s ladder to lift him high enough to get his camera lens up above the trees, he keeps his feet on the ground while he steers a remote-controlled drone camera in the sky above. His dog, Obie, will sit beside him as he works. They’ll often camp out in a tent when he’s on assignment.

His resulting before-and-after photos show what overgrown forests can become, and why restoring even more forests in many more places is worthwhile—even urgent. By taking steps like selectively cutting trees with chainsaws and grinding away smaller trees and shrubs with giant diesel-powered “masticators” (somewhat akin to a cross between a T rex and a super-sized grass trimmer), TNC forest managers are reducing the risk of dangerous catastrophic fire—by spacing trees—while at the same time ensuring light returns to the newly opened forest floor. This renews plant life, allowing huckleberries and big vibrant flowers to return, along with wildlife—even elk.

“It allowed plant life to flourish, plant life that had been suppressed by the deep shade. So it not only had a benefit of making the stand less vulnerable to fire—it made it much more hospitable to elk,” says Marshall.

In forests like these at Cle Elum Ridge, and across the dry forests of Western North America, the reason for restoring forests is there for all to see in the before-and-after. And that’s a good way to picture the future of these forests.

A series of three images from a location impacted by the Byrd Fire in 2012 in Washington state. This tree stand had forest restoration efforts before the fire, and the series of photos show the forest’s ability to withstand the 2012 fire and recover quickly.

"Here at The Nature Conservancy, we like to innovate and push the envelope, and we firmly believe that by trying new ideas, then assessing and adjusting our approach based on what we learn, we can improve forest health and help our communities become more resilient to wildfire impacts,” says Darcy Batura, TNC Washington’s director of forest partnerships. “The landscape is healthier, and our communities are safer as a result of this work, and I couldn't be prouder to be a part of that.”

Stay in the Loop

Get conservation stories, news and local opportunities from where you live.