Deer Browsing Is Changing the Character of Minnesota’s Forests

Research shows that the eating habits of white-tailed deer are reducing diversity in our forests, with consequences for nature and people.

In the late 1980s, the Encampment Forest along Minnesota’s North Shore was rich with old-growth trees. A vast canopy of white pine and white cedar estimated to be hundreds of years old created an enchanting oasis for wildlife and woodland plants.

There was only one problem. There were no young trees.

Despite the mature old conifers regularly producing seed, no seedlings were establishing themselves in the forest to bring up the next generation of old-growth trees. It wasn’t hard for scientists to find a culprit after observing huge clumps of needles missing from the few young pines and cedars—white-tailed deer.

Centuries ago, deer were rare in Minnesota’s Northwoods. But the landscape became more favorable after European settlers cut down swaths of forest for logging and agriculture. Today, deer are incredibly common in the Northwoods.

During the growing season, deer feast—or browse—on a variety of species like red maple, mountain maple and ash. During the winter, they browse on mostly white pine and white cedar. The easiest trees to reach are the young seedlings, which have a difficult time recovering from such damage.

What Does Deer Browsing Do to a Forest?

A study published by Forest Ecology and Management shows the long-term effects of deer browsing on Minnesota’s Northwoods based on decades of research in the Encampment Forest. In 1991, scientists constructed 10-foot-tall fences around three half-acre plots to keep deer out. They also identified three plots that were not fenced as control areas.

In 2008, researchers sampled every tree bigger than an inch in diameter to understand the long-term impacts of white-tailed deer.

Within fenced areas, there were abundant young seedlings and older saplings, particularly of white pine. All kinds of different sizes and species of trees were growing. The growth was so abundant, it was difficult for researchers to walk through the fenced areas.

Meanwhile, there was no regeneration of white pine or white cedar outside the fences. White spruce, a species with little nutritional value and rarely eaten by deer, had become the dominant tree. Balsam fir, which deer only eat under starvation conditions, was also abundant. Trees were sparse, brush was heavily browsed and the forest floor was nearly bare except for some sprigs of grass and a few spruce seedlings.

What Does This Mean for Minnesota’s Forests?

Deer browsing is causing our forests to become less complex. Forests are gradually losing diversity of tree species and shifting toward species like white spruce and balsam fir.

This will have consequences for people and nature. High deer populations could limit the amount of wood fiber produced by species that are preferred by deer, leading to decreased supply for the forest products industry and less carbon stored in our forests.

Forest songbirds and woodland species like pine martens, fishers and other small mammals will lose habitat because they depend on conifer forests that have a lot of dead wood on the forest floor.

Forests will also become less resilient to pests, diseases and climate change. For example, white spruce and balsam fir are projected to be highly vulnerable to a warming climate. Our forests will change over time to be more open areas with a few spruce trees and a lot more grasses. Once those grasses become well-established, it will be much harder to get trees growing again. It’s a shift in ecosystem structure that will change the character of our forests.

What’s the Solution?

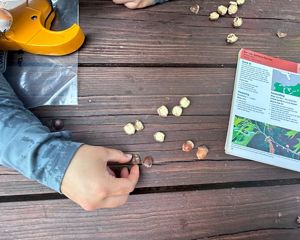

One of the main answers is forest restoration. We must plant more white pine and white cedar and other native trees. The Nature Conservancy is helping to accomplish this by planting climate-smart tree seedlings like white pine. Since 2005, we’ve planted more than 8 million seedlings in Minnesota!

Not only that, but we must protect seedlings from deer browsing. The study conducted in the Encampment Forest found that the fenced areas accumulated twice as much biomass as the unfenced plots. Deer browsing can be minimized with fencing around young trees and potentially by reducing the deer population so there’s less browsing pressure. The key is to manage our forests in a more balanced way so we can maintain their beauty, diversity and productivity.

Sign up for Nature News

Get monthly conservation news and updates from Minnesota right to your inbox.