Healing the West’s Waterways

Crews Are Showing How Simple Fixes Can Heal More Than Land

by Leah Palmer, Writing Manager

Stay in the loop!

Sign up to receive monthly conservation updates and opportunities to get involved.

Reviving Our Human Relationship with Water

By most standards, willow branches, juniper boughs, alder logs and rocks aren’t all that remarkable. But, to a guy like Gus Wathen, they are the keys to solving severe drought and limited water supply in the West. So, what do sticks and stones have to do with community resilience in a challenging climate? A lot, actually.

Wathen is a fish biologist at Anabranch Solutions, who works with The Nature Conservancy (TNC) to solve the impacts of drought in the West. He says he understood the sacred connection between humans and water since he was a boy.

“I’ve always loved the water. It’s this other world, and we as humans are not allowed there—except as visitors—as long as we can hold our breath,” reflects Wathen, who’s spent his career bridging the worlds above and below the surface.

For more than two decades, communities along the tributaries of the Colorado River Basin and throughout the West have held their breath as chronic drought became a reality. While drought is linked to a changing climate, it also goes hand in hand with a growing disconnection between humans and nature. We’ve lost our sacred reverence for water.

Communities in the West are keenly aware of their dependence on creeks and groundwater to fuel agriculture and other resources, like growing grasses for grazing cattle or providing healthy habitat for hunting and fishing. But not everyone acknowledges their responsibility to stewarding the land that provides so many resources, like drinking water for more than 40 million people.

A large portion of the Colorado River Basin is nestled within a mosaic of grasslands and shrublands called the Sagebrush Sea. This area provides habitat for hundreds of animals and fuels rural economies, but it is vanishing by 1.3 million acres every year due to drought conditions and invasive grasses.

The dual crisis of a vanishing habitat and limited water poses a weighty social and moral question: How do we protect water supply for future generations of people and nature? The answer requires the will for communities to revive their relationship with the land by rolling up their sleeves.

Restoring Connections through Hard Work

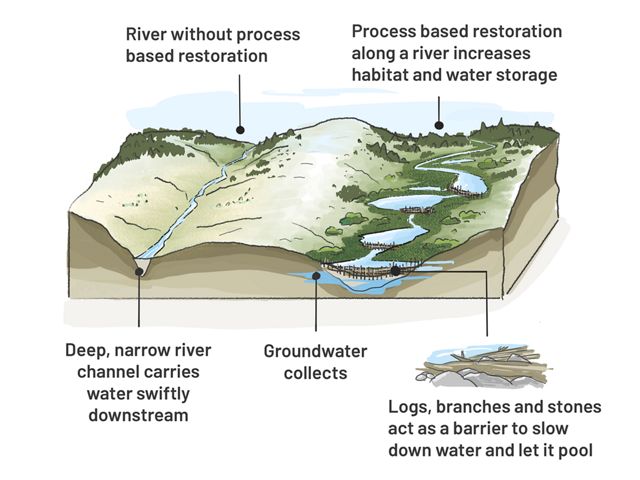

TNC has embraced a simple yet elegant solution for building resilience to drought in the intermountain West, called Low Tech Process-Based Restoration (LTPBR), a stewardship approach that brings curves and complexity back to streams, allowing them to store more groundwater for longer. “We’re not stopping the water—we’re just slowing and spreading it, turning a floodplain from a drainage straw into a sponge,” Wathen illustrates.

This graphic is an illustration of one river that is deep and narrow and carries water downstream quickly, alongside another with logs, branches and stones that act as barriers to slow down water and let it pool and collect as groundwater. The former scenario represents a river without process-based restoration, whereas the latter represents process-based restoration that increases habitat and water storage along the river.

Wathen and his field crews pack in post drivers, sledgehammers, hand saws, shovels, gloves, buckets and boots to a restoration site. They spend long days building impermanent structures that mimic the work beavers do along riverscapes, creating dams that capture water and provide habitat for a variety of creatures. Some of these human-made beaver dam analogues (BDA) are anchored to posts and others are attached only to the root structures the floodplain provides.

How do you feel about beavers?

Regardless of your answer, one must acknowledge two facts: beavers are incredibly industrious, and they’ve never had good PR.

Rustling in wetlands stumbles an architect. He strategically positions messy piles of brush in wetlands and riverbeds. With time, his work can restore balance and improve conditions for grazing animals, fish, amphibians and nesting birds.

In the wrong place, beavers are seen as ruinous, disrupting farms and interfering with urban drainage systems. To others, the beaver was a valuable commodity. Early 1900s fur trappers and traders pushed beavers to near extinction in North America, as consumers clamored to own fashion made of beaver pelts. After nearly going extinct, the beaver’s benefits to the land were all but forgotten.

For this interview, Wathen wears a vintage Portland Minor League ball cap. Stitched on the front is a mascot, the beaver. He’s clearly a fan.

Wathen shares that historically healthy riverscapes were made up of multiple, interconnected channels where water moved relatively slowly across entire valley bottoms. Today, many streams in the arid west are flowing too fast and cut too deep into incised channels. These disconnected, fast-moving channels let water rush through a floodplain before it can get a good drink. In contrast, a healthy stream moves slowly through curved and complex systems, allowing water to soak the surrounding ground.

Beavers are capable of “turning a floodplain from a straw into a wet sponge that turns vegetation green everywhere. The result can be a fire break,” Wathen explains.

At TNC, this work truly honors the get-it-done spirit of the beaver. Austin Rempel, riparian restoration program manager at TNC, is enthusiastic about beaver dam analogues as simple solutions to big problems. He explains TNC has entered a cooperative agreement with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to implement LTPBR projects across several Western U.S. landscapes. BLM provides access to public lands and regulatory oversight, while TNC connects with local landowners and manages the work on the ground.

“This is the kind of restoration that is perfect for BLM lands, and is super cost effective,” Rempel says. At low cost, and with minor technical training or advanced education necessary, LTPBR boasts a low barrier of entry for crew members to break into the conservation field. This builds a sense of belonging to both the land and the community.

Quote: Austin Rempel

LTPBR creates more jobs per million dollars invested than almost any other restoration method.

Rempel explains how river restoration benefits all parties’ bottom lines. “That’s because it relies on people using physical power to put wood back in streams. Simply put, they’re harvesting willows and doing what a beaver would do—building structures by hand. It takes crews of five to 10 people spending long hours in the river to make it happen, providing jobs that deliver results.”

Any materials that can’t be harvested directly from the land can be purchased from nearby industries, like quarries and sawmills. Rempel says, “it doesn’t make sense to ship materials from another country or another state.”

Rempel admits he has questioned if it would be “more cost-effective to bring back the beaver and let them do their thing? And quite often, yes, that’s the answer.” But he says the current social and ecological environment has left “quite a few streams in need of a nudge to make it safe for beavers to come back. Beavers will do the rest if we give them even a slight chance.”

Quote: Austin Rempel

Within a couple hours, you can go from someplace that feels like a desert to a place that feels like an oasis. I kid you not—by the end of the day, you can have dragonflies suddenly coming back.

Creating Jobs and Community

When TNC contracts Anabranch Solutions for work, Wathen takes great care to gather a field crew that functions more like a sports team than traditional coworkers. This summer, Wathen has assembled a mostly female crew.

“You don’t have to be best friends, but you have to trust each other and value each other’s strengths,” he says, drawing from his experience coaching his daughter’s Little League soccer team.

Between May and October, Wathen’s crews spend up to eight days working in wilderness conditions. They get six days off, and the cycle repeats throughout the summer. Regulations limit motorized equipment due to increased wildfire risk, so crew members hike from their cars to project sites, carrying food, water, camping gear and tools.

Crew members familiarize themselves with Anabranch's ten Riverscape Principles, one of which states, “It’s okay to be messy.” Others offer wisdom like, “There’s strength in numbers,” and “Let the system do the work.”

The work starts before sunup, to avoid oppressive midday heat. To avoid potential wildfire threat, any power equipment, like chainsaws, must be shut off by early afternoon. That’s when crews switch to working by hand.

It’s backbreaking. By the time daily goals are met, the crew is worn out. They end their days at camp, stretching and cooking for one another. “Our crews do a bunch of yoga afterwards. They stretch because they see taking care of their bodies is super important,” Wathen notes.

Quote: Gus Wathen

We’re not just restoring streams—we’re restoring processes.

While crew members could earn higher hourly wages elsewhere, the deep connection to land and community makes this work fulfilling—and worth staying for. As Rempel puts it, “This is a career where, after people complete their first project, they think, ‘I could do this every single day for the rest of my life.’”

Bringing Many Streams Together

Just as a beaver’s dam gains strength from its network of branches, TNC is building a resilient network of LTPBR practitioners to restore river systems across the Sagebrush Sea and Colorado River Basin. The urgency to act at scale is growing as quickly as the wildfires consuming the range.

TNC’s team now includes seven states, each with a staff member working full time to restore ever more miles of stream each year. These team members work together to share knowledge and expertise to increase the effectiveness of this vital restoration across the West.

“While we are by no means acting alone,” says Austin Rempel, referencing the incredible projects and partnerships headed by groups like Anabranch, Trout Unlimited, BLM and others, “our team is creating a West-wide network that brings the best ideas together no matter where they spring up, from Oregon to Colorado, Montana to Utah.”

Across borders and teams, our common focus is on the people who live and work in these landscapes and riverscapes. Communities must buy in to the benefits of restored riverscapes, as it falls to them to tend the land into greener summers, healthier rangelands and a better future for their families. We hope that by restoring fractured connections to place, communities and our public lands, together we find a way to keep streams flowing long into the future.