Science of Salmon

Illustrations by Erica Simek Sloniker/TNC

Salmon are inseparable from the health of the waters they inhabit—cold tributaries, dynamic rivers and quiet eddies where their lives begin. Yet these habitats are changing. Altered flows, warming waters and increasing intensity of wildfire in surrounding forests create new challenges for salmon as they journey from mountain streams to the Pacific and back again.

Wherever there are salmon, people come together to celebrate what they symbolize and what they provide. We marvel at their might, and appreciate their ability to sustain cultural traditions and livelihoods. Wild salmon connect the land and water, showing us that caring for the land plays a key role in how we care for our waters.

Across the Pacific Northwest, scientists for Tribal Nations, agencies and conservation organizations are working together to remedy these challenges—restoring rivers, rethinking fire and honoring cultures to ensure salmon remain a living thread that connects people, land and water for generations to come.

Reconnecting Salmon Pathways

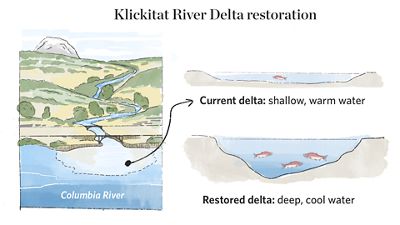

At the mouth of the Klickitat River, where it meets the Columbia, a quiet disruption unfolds for salmon and steelhead. A sandbar juts out, forming a visible line between the shallow sediment and the deep blue of the Columbia.

“Essentially, Bonneville Pool is a sandbox with some water on top,” says Bill Sharp, fisheries research scientist with the Yakama Nation.

This sandbar is more than a nuisance; it’s yet another barrier for salmon.

The Klickitat is one of many rivers along the Columbia’s mainstem where sediment buildup, caused by reservoirs and restricted water flow, has created warm, shallow deltas that fragment habitat and degrade the conditions salmon need to survive.

Sharp leads planning and restoration efforts for the Klickitat, working in partnership with the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, which manages salmon on behalf of the four lower-Columbia Tribes. Their goal is to remove the sediment and create deep cold-water pools for returning adult salmon. This would increase habitat connectivity for salmon, provide cooler plumes of waters to retreat to on hot days, and reduce incidences of predation.

Throughout his career, Yakama Nation elders and fishers have impressed upon Sharp the importance of returning the Klickitat and other rivers back to a productive place for salmon, and he sees it as a sign of progress for salmon recovery and a way to honor and protect the Yakama Nation’s resources and Treaty rights.

“I’ve been privileged to listen to the mission from Tribal Elders—to do what you can for aquatic habitats across the landscape we find ourselves in, to make it like it was,” says Sharp. “That also means producing hatchery fish that are fit to help contribute to natural production in a genetically, scientifically balanced way, and understanding how that ties directly back to the culture of producing fish to catch for ceremonial, subsistence and commercial harvest.”

The cold-water resources and the refuges of the Klickitat are vital for the region’s wild and hatchery fish, thanks to the diverse and unique rivers and wetlands of the Klickitat Basin, making restoration of the delta a top priority.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates.

Quote: Becky Flitcroft

“There is a perception that wildfire is a catastrophe for rivers, and for native fish, but it isn't always.”

Salmon Feel the Effects of Wildfire

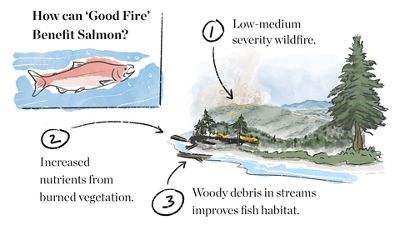

Wildfires shaped rivers and forests in the West for millennia. However, modern changes in fire size, frequency and severity can affect native species, like salmon. For example, severe wildfires in dry forest ecosystems reduce forest vegetation, making it difficult for water to absorb into the forest floor. This leads to runoff and erosion that alters water chemistry and buries salmon spawning gravels. But it turns out some other types of “good fire” also have benefits.

A group of scientists within the Science for Nature and People Partnership (SNAPP) are collaborating to understand the relationship between fire and salmon. Through multiple research projects, the team is synthesizing available research and data to quantify fish-fire relationships and identify factors that support fish resilience to fire. And the team is developing nifty tools for integrating wildfire management with salmon recovery.

Becky Flitcroft, research scientist and member of the SNAPP working group, spent years studying salmon. Her research on spring Chinook in Washington state’s Wenatchee River basin found that low- and medium-intensity fire improves habitat quality for adults and juveniles by adding wood to streams and increasing nutrients in the water.

“There is a perception that wildfire is a catastrophe for rivers, and for native fish, but it isn't always,” says Flitcroft, who is a research fish biologist with the USDA Forest Service.

In this way, forest restoration that emphasizes the use of beneficial fire, while reducing the risk of high-intensity wildfires, can support salmon across the Pacific Northwest. And salmon, in turn, help feed the communities and forests across the Pacific Northwest, filling our freezers and generously providing life-giving nutrients in riverbeds and on forest floors after they spawn, die and decay. These interdependent relationships between salmon, Pacific Northwest ecosystems and peoples are truly interwoven, creating a rich cultural tapestry for which this region is known the world over.

Made of Salmon

Learn more about the connections between people and salmon across the Pacific Northwest.

Make the Connection