Satellite trackers can reveal so much about the hidden lives of wildlife. A small, fist-sized tracker on a female sea turtle’s back can reveal how often she clambers ashore to lay eggs, or the thousand-mile journey she takes to get there.

But for conservationists, the key is using that data to better protect a species.

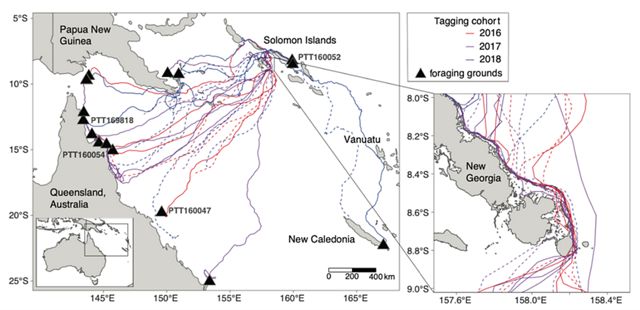

Nature Conservancy scientists spent three years tracking 30 hawksbill sea turtles from the Solomon Islands. The results of their study, published in the journal Biological Conservation, provided critical information to strengthen protection for turtles on their nesting grounds.

Three Decades of Turtle Conservation

The Arnavon Islands look just like any other Pacific atoll—palm-fringed and ringed by white sand and blue water. But these four small sand islands are also home to the largest hawksbill sea turtle rookery in the entire South Pacific. Turtles born here decades ago return to lay their own eggs, a journey so long that most turtles only return once every six or seven years. Females remain in the archipelago for several months, laying up to six clutches of eggs every two weeks before returning back to their foraging grounds.

In 1995, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) helped the communities of Kia, Katupika and Wagina establish the Arnavon Community Marine Conservation Area, creating both the largest and first community-managed marine protected area in the Solomon Islands.

Dr. Richard Hamilton, TNC Melanesia program Director, wanted to verify where the turtles returned to after nesting. “Protecting this species is a regional challenge,” he says, “and the tracking data could help identify potential migratory routes or foraging grounds which might be critical for their ongoing persistence.”

The tagging data helped answer those questions. Hamilton’s team used Fastloc® trackers, which record a GPS location every three hours, and then send the data back to Hamilton via satellite when the turtle surfaces for air. The tags work for an average of one year, long enough for scientists to follow them thousands of miles back to their foraging grounds.

From Tracking Data to Protection

Tracking data reveal that the Arnavons turtles return to foraging grounds across the South Pacific, including Australia, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. The average migration distance was 2,028 kilometers (1,260 miles), which is farther than any other known migration distance for hawksbill turtles.

“The real big surprise was just how many of them went back to Australia, to the Great Barrier Reef,” says Hamilton. “That’s really interesting and suggests that the population recovery we have seen to date is largely driven by the fact that these turtles are moving from protected area to protected area, albeit across 2,000 kilometers of open sea.”

The results also showed that the turtles spent 98.5 percent of their time within the protected area boundaries throughout their nesting period, indicating that the protected area is large enough.

Watching a turtle migrate in real time is interesting, but for conservationists, tracking a species is only useful when it can lead to better protection. In their study, Hamilton and his colleagues cite a review of more than 350 sea turtle tracking studies, which found that only 12 led to a change in conservation or policy.

Quote: Richard Hamilton

“By developing our research questions with the stakeholders in the Arnavons, we were able to use this information right away, we didn’t have to wait for the data to be published, we could just take action.”

That flexibility proved critical when two turtles from the first tagging cohort were poached in 2016. Sitting back in his office in Brisbane, Hamilton watched as one tracker—which should record a GPS location every three hours—went dark. A day later, a second tracker stopped working. Rangers later discovered that both turtles were killed as they came up on the beach to nest.

The Arnavon’s management board moved quickly to set up an additional ranger station on that island. And once the tracking data confirmed the protected area boundaries were sufficient, the government declared the Arnavons as the Solomon Islands’ first national park. That designation gave the rangers legally recognized enforcement powers and enables the government to issue fines of up to SBD $10,000 to individual poachers.

“For more than two decades I have seen poachers walk away free because of a lack of strong laws to punish them, so I have been swallowing my anger and frustrations for that long,” says John Pita, TNC’s environmental coordinator for Isabel province. “This is what we have been dreaming of for the last 20 years.”

Turtle Tales: A Conversation with TNC Scientists

Moderated by The Nature Conservancy Director of Gender & Equity in Asia Pacific, Robyn James, Melanesia Program Director Rick Hamilton and Conservation Officer Madlyn Ero share stories from the field on how we’re creating a brighter future for sea turtles in this webinar.