By Fred Kihara, TNC Africa Water Funds Director

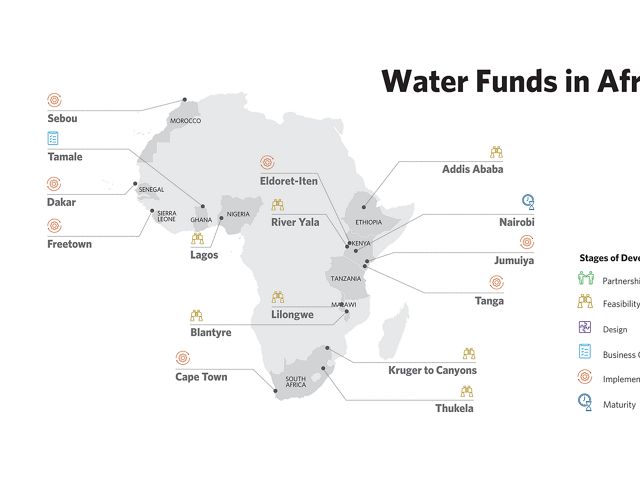

Just three years ago, we had two water funds in Africa: The Upper Tana-Nairobi Water Fund and the Greater Cape Town Water Fund. Today, our map includes 16. This tremendous growth is thanks in great part to our strategy of equipping and inspiring partners in new cities to learn fast and adopt the model.

Many times people seek out TNC because there’s something going wrong with their watershed. Some have tried a few things and they’ve not gotten the success they would desire. The water funds model, which we’ve adapted to African conditions, can give them the results they’re looking for.

It’s been tested elsewhere in the world for 22 years. It works. It engages public and private stakeholders; it engages communities; it brings everyone together to implement nature-based solutions for water benefits, community benefits, biodiversity benefits, and climate benefits.

There are lots of places on this continent that can really benefit from implementing the water fund approach. The 16 places on our current map could double or triple.

Each water fund is the result of a long and complex journey, together with many stakeholders. The icons on our Africa water funds map signal which milestones have been completed on that journey.

Partnership in Place

If our scientists determine that the biodiversity value of a watershed is such that conservation there would contribute substantially toward our 2030 Global Goals, TNC may take the lead.

If a watershed doesn’t meet our criteria for taking the lead but there’s strong local interest in utilizing the model for stakeholder engagement, broader conservation goals, and awesome benefits for people, we may instead encourage peers working in that landscape to take it on. We provide the resources they need, including coaching, materials, and fundraising capacity, and they can be the boots on the ground.

We’ve developed a standardized methodology, which we share through the Water Funds Network and the Water Funds Toolbox, a comprehensive online training program. Seventy percent of the continent's water funds are being led by partners with TNC only providing mentorship, which means we can scale faster.

Sign up for Nature News

Get monthly conservation news and updates from Africa.

Feasibility

It’s a rigorous process, several months long, to determine together with all stakeholders, including communities, is it a go, or is it a no-go?

We conduct an extensive analysis—on ecological, institutional, and other factors—to identify the problem and potential solutions, and to get stakeholders aligned. TNC brings the best scientific knowledge to the process so that people can make the best decisions. We look at the extent of the work that needs to be done and we have to satisfy ourselves that that goal is achievable, and that the stakeholders are willing to collectively take action, contribute, and succeed.

Business Case

Science tells us which actions to take to get the desired results; a thorough economic analysis tells us the potential return on investment of those actions. For example, we found that that watershed restoration can reclaim two months’ worth of water supply for Cape Town each year at half the cost of other approaches, such as desalination of sea water.

If you put the potential benefits in economic terms, people buy in.

The government of Cape Town has already contributed $3 million USD to the Greater Cape Town Water Fund, and this year, they renewed that commitment for another $3 million. The government of Sierra Leone pledged $2 million to the Freetown Water Fund. And the Kenyan government is investing $3 million into the Eldoret Water Fund. These are huge steps toward sustainability, and votes of confidence in the model, which will inevitably help inspire other national and municipal governments to do the same.

Design

This stage includes the difficult work of establishing a strong platform to convene and coordinate stakeholders in order to collaborate effectively. To succeed and to last, a Water Fund must be a legal entity with a steering committee that includes government, the private sector, and communities. Collectively, we determine how we are going to work together to get the job done.

Implementation

Now we put the science to work. We start with pilot projects and monitor the impacts. We listen to communities. Once we know which actions work best in real world conditions, we scale those up.

(In some instances, such as with the Tanga Water Fund, there may be elements of conservation action that are so readily apparent and urgent that partial implementation may begin even before the prior steps of water fund development are fully complete.)

I’ve seen proof that you don’t just succeed in the primary goal of conservation and the secondary goal of improving water security for millions of people in an urban center, but you’re also supporting communities to come out of poverty.

For example, I’ve met farmers who, through interventions brought to them by the Upper Tana-Nairobi Water Fund, have doubled or tripled their income. Farmers have planted a million new fruit trees, raising local income by $50 million annually across the watershed, while also keeping sediment out of the river. Today, more than 50,000 farmers are using more sustainable practices and their lives are better for it.

Maturity

This is the ultimate wish for every parent. The endowment is capitalized so there’s a reliable source of funding for conservation. There’s strong, inclusive governance in place. An independent entity has been established to continue the work for the long-term.

The first Water Fund to achieve maturity was in Quito, Ecuador, TNC’s first Water Fund, which was launched two decades ago.

Now, a second has reached maturity: the Upper Tana-Nairobi Water Fund, now called the Upper Tana-Nairobi Water Fund Trust.

The question I ask myself is: “How can it become one day a movement where Africa water funds have gotten three or four or five million people out of poverty, and supported 10 million acres of degraded land to become sustainably managed?”

This is why I always want to keep on expanding the bounds and saying we can go further. This is the true spirit of Ubuntu: We can go much further together as a continent.

As the legendary Kenyan marathon runner Eliud Kipchoge famously said: “No human is limited on our continent.”