Five Ways Wildlife Keeps Conservation Moving

By protecting animal migrations and movement, we can build a healthier, more resilient plant.

From elephants to sardines, the movement of wildlife across Africa’s great landscapes is a spectacle of nature.

Africa hosts some of the most incredible wildlife movements in the world, from the thunderous migration of wildebeest across Tanzania and Kenya, to the convergence of massive sardine schools with lush plankton blooms off the coast of Angola.

If we listen to the messages that animals send us with their movements, we can better understand how to conserve and protect the lands and waters on which they depend.

Here are some of the ways wildlife moves across some of Africa’s most iconic and irreplaceable places.

The wildebeest migration between Tanzania’s Serengeti and Kenya’s Maasai Mara is an epic journey of thundering hooves, as millions of these majestic mammals follow a cycle of seasonal rains and the grasses that grow in their wake. But the search for food and water is not the only reason for these species’ movements. Breeding and the subsequent need to protect and feed calves are fundamental reasons for the Mara-Serengeti migration.

The nutrient-rich volcanic short-grass plains of the southern Serengeti and Ngorongoro plains nurture the more than 400,000 calves born each season. And the massive herds find safety in numbers, as their large numbers overwhelm predators and give the calves a higher chance of survival.

The wildebeest are not alone during this move—roughly 300,000 zebras lead the wildebeest along their journey. TNC and its partners in Kenya and Tanzania are working hand‑in‑hand with local communities to keep the vital wildlife corridors of this world‑renowned migration open and ensuring they are preserved for generations to come.

Spanning Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, KAZA is the world’s largest terrestrial transfrontier conservation area. It is defined by its vast open spaces, seasonal wetlands and ancient river systems, with 3 million people living alongside spectacular wildlife. One of Africa’s Big Five Irreplaceable Landscapes, the Greater KAZA landscape is home to half of Africa’s elephants, 15% of its lions and a quarter of its wild dogs—more than half a million square kilometers of connected lands where these species still roam freely. TNC is working across the KAZA landscape to ensure these migratory routes remain open and functional.

Across thousands of kilometres of KAZA landscapes, packs of wild African dogs follow their prey, oblivious to the invisible borders separating protected national parks from surrounding communal lands.

Wild dogs need significant amounts of lands to function healthily within their ecological cycle.

These packs move from the Kafue National Park to game management areas where communities are actively working to conserve spaces for wildlife and further to open areas, and back again—sometimes their journeys cover several thousand kilometres and take them across international borders into countries like Mozambique.

This movement was once risky for dogs. In the past, wandering outside of the National Park would have led many wild dogs to be snared or shot. But TNC and our partners in the areas around the park have helped make these spaces safer by providing funding for protection operations, including vehicles, fuel, community scouts’ salaries, equipment, rations, training and wildlife monitoring. With significantly increased resources for protection around that landscape, the wild dogs are now able to transition between those protected areas and are more secure in areas outside the National Park than they used to be.

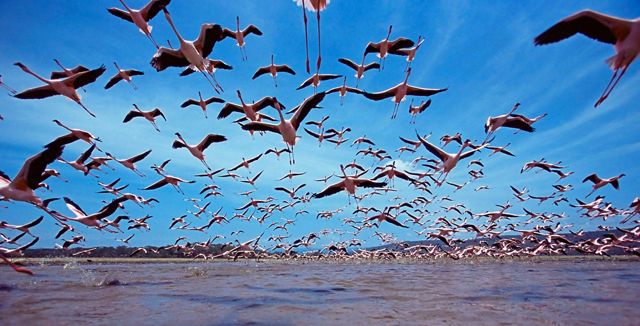

In Africa’s Great Rift Valley, there are seasons when ribbons of pink light up the horizon. Tens of thousands of flamingos rise from alkaline lakes forming one of Africa’s most striking migrations. Flamingos migrate between shallow soda lakes scattered across Eastern and Southern Africa in search of algae and cyanobacteria—their favorite food.

By moving between Lake Natron in Tanzania, Lake Bogoria and Lake Nakuru in Kenya, and Botswana’s Makgadikgadi Pans, flamingos find nourishment, avoid disease and predators and maintain genetic diversity. Their movement also benefits ecosystems: feeding activity redistributes nutrients, supports microorganisms and links distant lakes into a single ecological network.

But this migration is under threat. Water extraction, mining, infrastructure and climate change all disrupt the delicate balance of Africa’s soda lakes. Because flamingos rely on multiple sites, losing even one can destabilize the entire system.

Protecting flamingos means protecting the interconnected water systems that allow these pink rivers to flow across Africa’s skies. The Nature Conservancy is working upstream of these African lakes, restoring and maintaining forested water towers to protect water supplies, water quality and shelter at the source.

All year long, elephants are on the move across Tanzania, following food and water between the country’s protected lands and its villages. In the dry season, an impressive 10,000 wander into Tarangire National Park in search of the food offered by its permanent water supplies, accompanied by a dizzying diversity of mammals seeking the same sustenance: wildebeest, zebra, giraffe, buffalo, oryx, ostrich and lions.

As the rains bring more plentiful food to the surrounding areas, the animals leave the park and disperse farther afield. Along the way, the elephants loosen up the ground with their heavy hooves—which lets in grass seeds that then germinate when the rain arrives.

Elsewhere during the dry season, elephants move across areas of high and low population density within the Greater KAZA, which is home to more than 200,000 individuals in need of safe corridors. In Zambia’s far northern corner of the Greater KAZA landscape between Kafue National Park and the West Lunga ecosystem, elephants are on the rebound. West Lunga was once renowned as a breeding refuge for elephants, with estimates of up to 10,000 before the poaching epidemic of the late 20th century, which significantly threatened their safety. In 2022, only roughly 25 elephants remained in West Lunga.

Now, thanks in large part to local efforts to restore and reconnect landscapes across connected conservation corridors, roughly 120 elephants have made the journey from the Kafue National Park to what is now a safe haven in West Lunga. Along these crucial migration routes, TNC is involved in several community conservation initiatives that secure wildlife connectivity while supporting community livelihoods.

During the great zebra migration of southern Africa, one of the continent’s last remaining large-scale wildlife movements, the horizon comes alive with thousands of black-and-white striped bodies guided by water and grass.

As the dry season tightens its grip on the Makgadikgadi and Nxai Pans National Parks, the herds begin their northward journey toward the Okavango Delta and Chobe National Park, where permanent water and grazing sustain them through the harshest months. When the rains return, transforming the pans into vast grasslands, the zebras turn south once more.

Covering hundreds of kilometers across open rangelands and wildlife corridors, this round-trip journey is one of Africa’s longest remaining zebra migrations. The journey also keeps the ecosystem in balance: constant movement prevents any one area from overgrazing, and healthy populations of predators like lions and hyenas follow in their wake. And balanced ecosystems support tourism, livelihoods and local economies.

For generations, zebra migrations have shaped grassland and woodland ecosystems across Africa—not to mention the animals, cultures and communities depending on them. But many migrations have vanished, cut off by fences, roads, farms and settlements. Once a corridor is blocked, migration can collapse, often silently, and often permanently.

Along Africa’s southern and western coastline sweeps the Blue Benguela Current, enriching the continent’s most productive ocean area. The Blue Benguela flows north from South Africa to Angola, intersecting with productive estuaries and rich fisheries and sustaining 40 million people along the way.

Here, movement is constant. Cold, nutrient-rich waters flow from the ocean’s depths to its surface. This phenomenon, called upwelling, drives wildlife movement at a massive scale: sardines, anchovies and other small fish follow plankton-rich blooms, which, in turn, attracts predators such as Cape fur seals, dolphins and seabirds.

The Blue Benguela current is an important cool-water migration pathway for humpback whales, who seasonally swim up and down Africa’s Atlantic coast to reach their feeding grounds in the Southern Ocean and their breeding areas off Angola, Gabon and the Gulf of Guinea.

These migrations—and the currents that move them—are essential for many species’ breeding and feeding cycles. However, overfishing, pollution and climate change are throwing off these carefully calibrated cycles and disrupting traditional movement corridors. Abnormally warm surface temperatures and reduced oxygen are breaking the food chain that sustains migratory pelagic fish. This, in turn, hurts the region’s coastal communities who rely on fish near the shore for healthy protein.

The Nature Conservancy and our partners in the Blue Benguela Partnership aim to ensure that the rich ocean diversity, productivity and coastal catchments are effectively managed to sustain and enhance human and ecosystem well-being for present and future generations.

Africa’s wildlife migrations and movements are more than natural wonders—they are indicators of ecosystem health and early warnings of environmental change. When we safeguard migration routes and restore connectivity, we help ensure that wildlife, people and landscapes thrive together, which is what TNC is prioritizing as it focuses its work on some of Africa’s irreplaceable landscapes.