Baptism by Fire

A new generation is picking up the drip torch to give Iowa prairies the phoenix treatment.

Originally published in Little Village Magazine

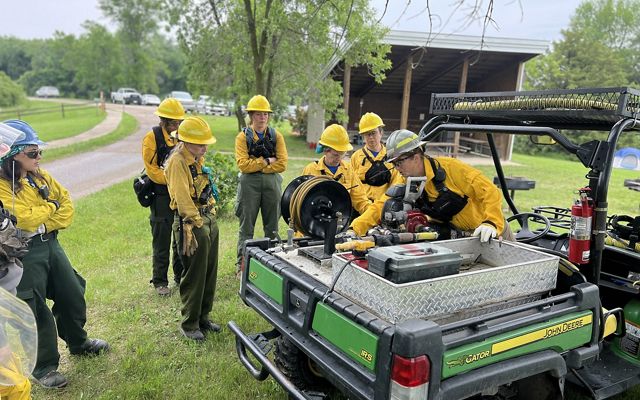

Just after 12:30 p.m. on June 2, a group of 13 women and nonbinary folks gathered in a loose circle at the base of a ridgeline at Stone State Park. They were dressed in the standard outfit for prescribed-fire practitioners: flame-resistant Nomex yellow work shirts and green pants, heavy leather boots, yellow helmets and shatter-resistant glasses. Drip torches, bladder bags and fire rakes were arranged in a line nearby, and a small utility vehicle held a water pump.

It was the second day of the Trailblazers Academy, a multiday prescribed-fire workshop facilitated by The Nature Conservancy and held in the rugged Loess Hills of western Iowa. The previous day, the 40 participants, each with varying levels of fire experience, rotated through a variety of training sessions, which included learning about basic medical aid, fire hand tools, ignition techniques, operating the radio, writing burn plans and the correct way to “sling weather” to track the relative humidity. Now, they were split into groups and deployed to units across Plymouth County, where they would put fire—good fire, intentional fire—on the ground.

Melanie Schmidt, the burn boss for this particular crew, passed out maps to each member. They were tackling a 13-acre unit that hadn't been burned in 10 years, she explained, and because there was barely any wind, topography would play an outsized role in the way the fire moved.

“The objective of the burn today is we want to set back some of that woody encroachment in the unit, specifically the sumac and other woody species like dogwood that are in here.” She gestured toward the hillside. “We also want to help invigorate the native prairie.”

Schmidt split the crew into two units, Alpha and Bravo, each led by a squad boss. Alpha would take the hillside along the road; Bravo would work above the prairie ridgeline. After explaining the escape routes, fuel breaks, safety hazards and water sources, Schmidt cleared her throat. “Would anyone like to decline the assignment?”

When no one declined, she clapped her hands and smiled. “Great!”

It was time to burn.

When people think of fire in a landscape, they often envision wildfire in the West, where tall flames engulf whole structures and burn through thousands of acres of forest, emitting thick blankets of smoke that last for days or weeks.

But most ecosystems in the United States have evolved to adapt with fire, and the prairie is no exception. Historically, grasslands burned through both lightning and human activity. Indigeneous peoples across the Great Plains used—and still use—prescribed fires to manage game populations, create travel routes, maintain healthy watersheds and enhance biodiverse habitats, as well as for cultural purposes.

With European settlement, though, came fire suppression. Without regular fire on the landscape, woodland areas and forests encroached on the grasslands, and today less than .01% of Iowa’s tallgrass prairie remains. Ironically, suppressing fire only increases the risk of wildfire, especially as years of drought and decades of climate change create more extreme and unpredictable behavior.

“Good” fire is intentional. It reinvigorates ecosystems, cuts back on encroaching woodies and invasives, reduces wildfire fuel and enhances pollinator and grazing habitat. Putting good fire back on the landscape is one of the cheapest and most effective tools in conservation and land management.

“Bad” fire, in comparison, destroys everything.

Up on the ridgeline, where the dry grasses were receptive to the fire, it was easy for the Bravo crew to “build black,” creating blackened soil that acted as a fire break. The flames were low and slow, making it possible to step through them. As the fire’s heat increased, the updraft wind funneled the smoke in an opaque vertical column, turning the air singed and sweet. To ensure that any flames lit from Alpha below wouldn't rip up the hillside and crash into them, the Bravo crew “fired ahead,” moving more quickly along their line.

On the hillside below, however, the Alpha crew struggled to build black. The shade and the rain from earlier in the week led to higher moisture levels, making it harder to light the ground with drip torches. Even when fire did catch, the orange flames crept feebly along the slope for only a few moments before disappearing.

The steep incline didn’t help. One member of the line crew fought her way through crooked thickets of sumac and wild raspberry, drip torch in hand, before breaking through vines and stumbling onto the road.

“I feel like I just experienced rebirth,” she said. The crew kept chugging along, doing the best they could. Prescribed fire doesn’t play by luck. It plays by wind, topography and humidity; sometimes the conditions aren’t favorable for a burn, especially in the growing season of summer.

The burn itself took only an hour. Afterwards, the entire crew walked through the unit for “mop up,” a process of extinguishing any remaining embers with water or hand tools. Atop the ridgeline, the soil was blackened, the small dogwood trees shriveled and scorched. To the untrained eye, the jet-black earth may have seemed foreboding, but the crew was satisfied. Within weeks, green shoots of native grasses and wildflowers would start sprouting up through the soil.

Stay in the Loop.

Get conservation stories, news and local opportunities from where you live.

The Trailblazers Academy takes place over three days at Camp Joy Hollow, a former Girl Scouts camp on Broken Kettle Grasslands, a preserve owned and managed by TNC. The first full day is filled with training sessions; the other two days are dedicated to live fire. This year, participants burned 335 acres in the Loess Hills across a mixture of tallgrass prairie, oak savanna and wetland habitats.

A program like Trailblazers Academy requires an equal amount of passion and planning to bring to life. Luckily, Amy Crouch is short on neither. Back in February 2023, Crouch, the Little Sioux project director for TNC and longtime prescribed fire practitioner, overheard a colleague discussing the Women’s Woodland Stewardship Network, a program run by Iowa State Extension that aims to empower women in forest and woodland stewardship.

“It got me kind of thinking, what about doing that for women in fire?” Crouch said.

She floated the idea to her boss, Scott Moats, the director of Land and Fire Management for TNC in Iowa. Moats was supportive of the idea, and Crouch immediately got to work. She connected with the outreach team at Iowa State Extension and attended the annual Iowa Women in Natural Resources Conference, where she workshopped the structure of the program with other fire practitioners and conservationists.

During the first year of Trailblazers Academy, there were 26 participants; this summer more than 100 people applied for 40 spots. The fire experience of the participants ranged from beginner to advanced, and they came from states as near as Nebraska and as far as California. The goal of the Trailblazers program was to provide each participant with the opportunity to grow, whether that’s through mentorship, leadership or achieving specific task-book objectives—such as operating a fire engine or implementing a fire plan—to obtain the next professional qualification.

Although the Trailblazers program is open to applicants of all gender identities, the focus of the program is to empower female fire practitioners by providing a safe and supportive environment. Such an environment is needed—a 2020 study from the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) shows that only 9% of combined volunteer and career firefighters are women.

Quote: Alex Garcia

I liked coming here because I can see other women leaders, how they lead, how they speak, how they brief other people, how they communicate.

Before attending Trailblazers, wildland firefighter Alex Garcia never had a non-male supervisor. “I liked coming here because I can see other women leaders, how they lead, how they speak, how they brief other people, how they communicate,” she said.

Other participants agreed.

“Being on a line with all women is a great opportunity to ask questions and learn new things,” said Destiny Magee, a land steward for the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation and one of the few returners from last year's program. “Fire is usually go go go, and there’s not much room to ask questions.”

Perhaps the greatest gift of a program like Trailblazers is the opportunity to see yourself in a new light, as Ruth Campos discovered. Through her six years of experience working in wildland and prescribed fire, Campos is familiar with being one of only a few women—particularly women of color—on a fire crew. Prior to Trailblazers, she found herself wondering whether a career in fire was worth all the sacrifice it required.

So when a leader of the Trailblazers asked her to be a burn boss for Thursday’s unit, Campos was taken aback. The role of a burn boss is to organize and manage all aspects of a controlled burn from start to finish, and getting to that level of qualification usually takes anywhere from 10 to 15 years. But she accepted the challenge, knowing that she would have on-the-ground support from a mentor.

On Thursday, she bossed her first burn on the Knapp Prairie Preserve with great success.

“It felt like being a director of a symphony,” she said afterwards. “I had a plan, I directed it and then I watched it all play out from a distance. It felt beautiful.”

The experience of burn bossing made Campos realize what was possible for her own career.

“I didn’t see myself in that role before,” she said, then paused for a moment. “And now I want it.”