Chasing the Shade: Expanding Philadelphia’s Tree Cover

The Inflation Reduction Act is helping implement the city’s plan to equitably plant trees.

Growing up in South Philadelphia’s Grays Ferry neighborhood, Meeka Outlaw remembers her grandmother, Willie Frank Outlaw, chasing the shade on the days when summer’s heat and humidity would combine to make her neighborhood nearly unbearable.

“She lived on the sunny side of the street, but the sun was lower in the morning, and she was able to sit in the shade, visiting with anyone who passed by,” Meeka remembers. There were no trees nearby, so as the sun rose, “she’d go across the street and sit with my aunt, her daughter, because there was shade. And when the sun went down, she’d go back to her own porch, unless it was so hot that the steps were too hot to sit on.”

Another memory: childhood trips to Sesame Place, a theme park based on the popular children’s television show Sesame Street. The family could take the bus to the park, located in suburban Langhorne, Pennsylvania, and back again to Grays Ferry. Like many American metropolitan areas, historically underserved neighborhoods and communities of color have significantly less tree cover than wealthier, whiter communities. The difference between Outlaw’s South Philadelphia neighborhood and tree-lined Langhorne was easy to both see and feel, she recalls.

Quote: Meeka Outlaw

“Coming back into the city, you really felt the heat,” she remembers. “It was like an imaginary border that showed where Langhorne ended and Philly began. The air was thick and hard to breathe, like walking into a kitchen that has the oven on.”

Outlaw, now a school teacher, returned to Grays Ferry after college. Her home has air conditioning now, but Philadelphia summers are even hotter thanks to climate change, and South Philly is one of the hottest parts of the city. So in 2023, she was happy to hear that the Forest Service gave $12 million from the Inflation Reduction Act to a public-private coalition to help implement Philadelphia’s new, comprehensive plan to equitably expand Philadelphia’s urban tree canopy.

“You shouldn’t know that you’re in the suburbs because the temperature has drastically changed,” she says. “And you should be able to walk down the street and see a place where you can sit underneath a nice, shady tree.”

The grant will provide funds to support implementation of the Philly Tree Plan, a 10-year strategy which identifies priority areas for expanding the city’s tree canopy. The Nature Conservancy served on the Philly Tree Plan Steering Committee and is one of the partners assisting with the joint implementation of the city’s first-ever urban forest strategic plan.

How the IIJA is Helping Build Urban Tree Canopies

-

$12M

The Forest Service awarded millions from the Inflation Reduction Act to expand Philadelphia's tree cover.

-

385

Philadelphia's grant is one of hundreds awarded by the Forest Service to boost tree cover in communities across the country.

-

10.5

Neighborhoods in Philadelphia that didn't have many trees or green spaces were over 10 degrees warmer than other parts of the city.

Explore the StoryMap

This user-friendly resource highlights the study’s findings and Philadelphia’s tree plan.

Learn more about the need for treesStudies show that communities with access to trees and green spaces experience improved health outcomes and economic opportunities, reduced crime and lower average temperatures, according to the Forest Service. The grant to Philadelphia is one of 385 awards funded by the Forest Service to boost the nation’s tree cover in communities across the country.

Outlaw and her 14-year-old son, Rashid, helped inform the plan by participating in a heat mapping project funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and led by Richard Johnson at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. On a hot July day in 2022, they were among dozens of Philadelphia residents who took to the streets to gather data as part of the Philadelphia Urban Heat Mapping Campaign. Driving their own cars, which were outfitted with heat sensors— affectionately referred to as “snorkels”—participants drove slowly through the city, while the sensors measured the heat and humidity once every second in the morning, afternoon and evening.

“Starting at 6 a.m., we drove around the city,” she says. “The route ended at this park surrounded by trees, and you could tell how much cooler it was near those trees.”

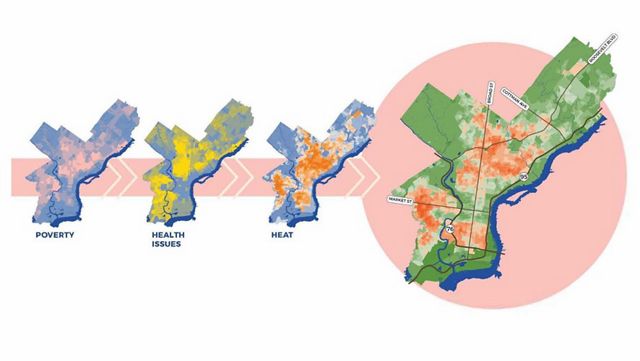

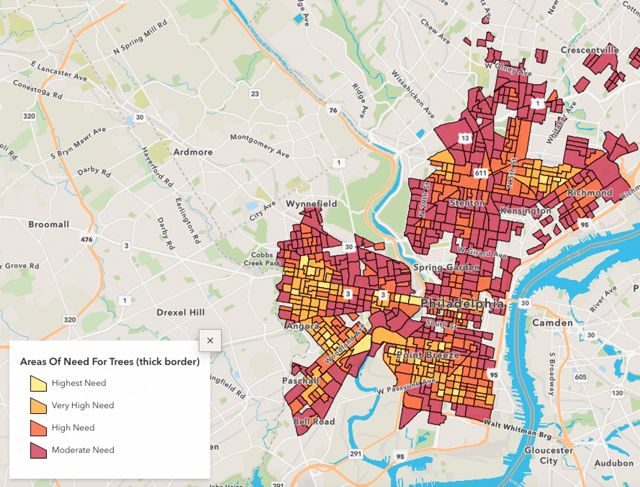

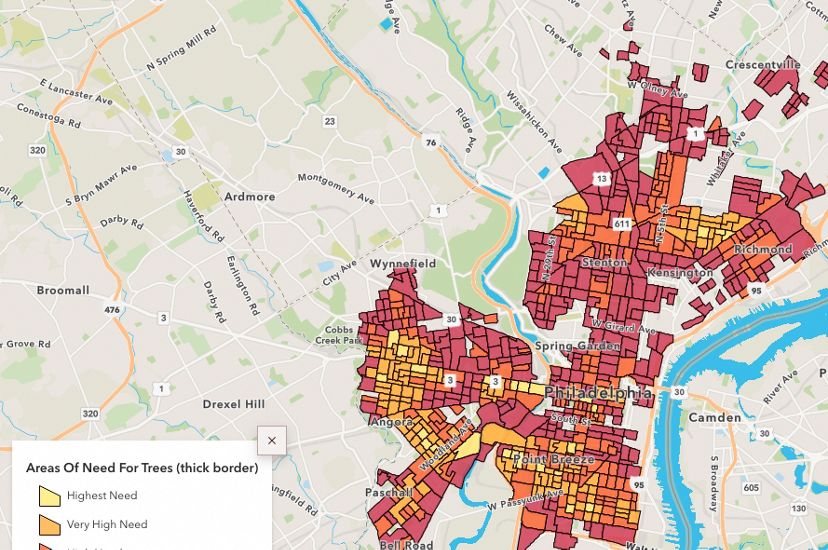

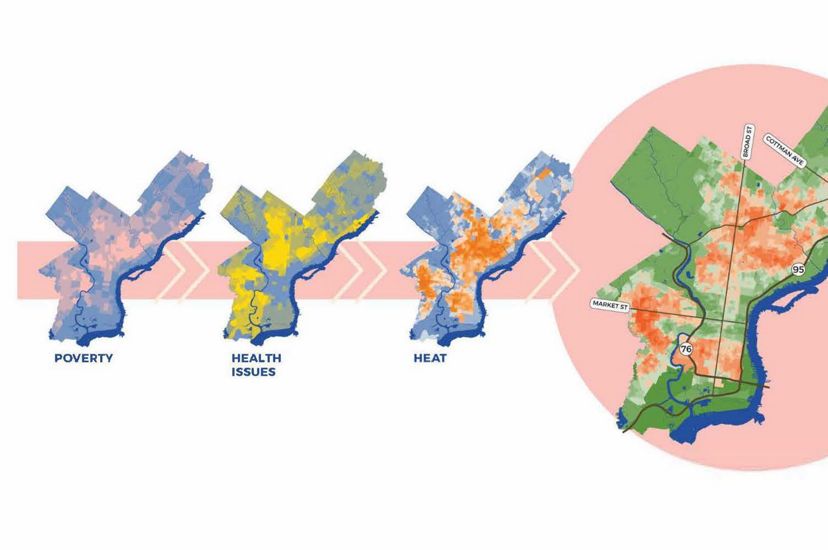

The measurements from the volunteers, who covered 105 square miles of the metropolitan area in a single day, were combined with information about existing tree canopy and social factors, like income and health, and used to identify the greatest areas of need for increased tree cover, says Richard Johnson, now the urban climate resilience manager for TNC’s Pennsylvania and Delaware chapter.

“The map shows the hottest, most heat-vulnerable areas of the city that have the least amount of tree canopy,” says Johnson. For example, “Grays Ferry is an area of critical need for trees. The neighborhood has just 6% tree canopy, one of the lowest in the city.”

Quote: Richard Johnson

Grays Ferry is an area of critical need for trees. The neighborhood has just 6% tree canopy, one of the lowest in the city.

Satellite imagery, currently the most common method for measuring urban heat, “doesn’t really show what the heat is like on the ground,” he says. The heat mapping campaign measured air temperature and humidity to “get the real feel of what people are experiencing.”

The high temperature for the day was 95 degrees, but temperatures soared as much as 10.5 degrees higher in some areas than others on the survey day. The study revealed that areas with more concrete, roads, parking lots and fewer trees trap heat, making them hotter on average. Tree-dense areas, on the other hand, stayed cooler throughout the day.

The analysis confirmed that the Philly Tree Plan could be transformational in equitably addressing extreme heat, public health and quality of life for Philadelphia neighborhoods. An interactive ArcGIS StoryMap that TNC developed in collaboration with city partners, not only shows the results of the study but also the benefits of trees and how to get involved in tree planting and care activities around Philly.

Outlaw has more than trees on her mind. Her beloved neighborhood is gentrifying. Housing prices and rents are skyrocketing, and her Black neighbors in Grays Ferry are being displaced by an influx of whiter and wealthier residents. She hopes that she can afford to stay in her home and her children can stay in Grays Ferry for years to come. And as trees begin to grow and the shade spreads to both sides of the street, “My hope is that when and if these changes do happen that I’m living in the neighborhood to see it.”

Outlaw’s comments reflect the concerns of many long-time residents who fear greening may exacerbate gentrification by increasing property values. The Philly Tree Plan represents an opportunity to ensure that existing community members benefit from the plan’s historic investments.