Canadian Leaders Back Nature as a Climate Solution—So Does Science

In Canada, a new study showing the potential of natural climate solutions will help bolster ambitious climate targets and drive bold action to reach global 2030 goals.

By Amanda Reed, Director of Strategic Partnerships, Canada Program

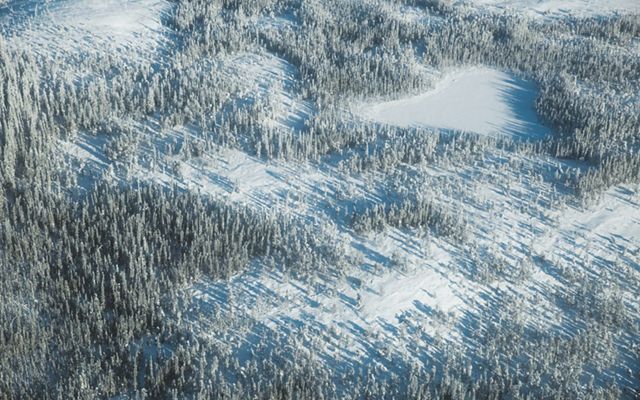

In Canada, nature is one of our most powerful allies in fighting the climate crisis. Nearly 40% of the country is covered by carbon-filtering trees. One-quarter of the world’s remaining wetlands are within our borders, sequestering greenhouse gas emissions in marshes, bogs, and swamps. Even our grasslands—a globally endangered ecosystem—stretch across three provinces, storing emissions beneath 26 million acres.

It seems logical that the country would embrace natural climate solutions (NCS)—actions to protect, manage and restore grasslands, wetlands, forests and agricultural lands to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and fight climate change.

Key Findings

Learn more about the groundbreaking results and what they mean for Canada.

See the ResultsAnd in fact, Canada has. Over the past two years, the federal government has announced a total of US$3.3 billion ($4 billion CAD) to implement NCS, including commitments to plant 2 billion trees and investments to help elevate the role of foresters, farmers, ranchers and Indigenous governments in these strategies. Just last month, following the Leaders Summit on Climate hosted by President Biden, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau updated Canada’s global climate target, making it one of the most ambitious in the world.

As more and more bold commitments are penned, Canadian decision-makers have begun asking more questions about how to move forward: Where should we prioritize natural climate solutions? How much should we invest? Will natural climate solutions hurt our forestry or agriculture sectors and the rural communities that depend on them for their livelihoods? We also lacked the answers to some thorny science questions that matter in Canada.

Now, thanks to research led by Nature United (the Canadian affiliate of The Nature Conservancy) along with 38 experts across Canada and the U.S., we have many of the answers. The study, “Natural Climate Solutions for Canada,” published this month in Science Advances, examines 24 pathways that, if implemented to their full potential in Canada, could prevent or sequester 78 Mt of CO2e annually in 2030—the equivalent of powering every home in Canada for about three years.

Quote

If implemented to their full potential in Canada, natural climate solutions could prevent or sequester 78 Mt of CO2e annually in 2030.

Surprisingly, it’s not forests that play a starring role in NCS in Canada. Improving agricultural practices—such as planting cover crops and more efficiently managing fertilizer use—make up nearly half of the total opportunity and many cost less than US$39 ($50 CAD) per metric tonne. The lower-than-expected opportunity in forests is due to several factors: the fact that Canada’s forestry sector is already using relatively sustainable practices; the economic safeguards we applied; the fact that trees take a long time to reach their maximum potential for sequestering and storing carbon, and the albedo deduction.

The latter is a unique aspect of this science: The “albedo effect” refers to the reflectivity of sunlight particularly in forests. Localized warming can be caused by increasing tree cover (such as through planting trees), which decreases the amount of sunlight reflected (even as trees take greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere). To account for this, the results include an “albedo deduction” to provide more accurate estimates of mitigation—something that’s missing from most global tree-planting studies.

Within the 2030 timeframe, actions to restore forests by planting trees can deliver 0.1 Mt CO2e per year. But if you forecast out to 2050—as the study does—these forests will store large amounts of carbon and planted trees will be growing fast enough to offer substantial mitigation potential of 24.9 Mt CO2e per year.

Another key takeaway is that the highest mitigation potential comes from protection and management of old-growth forests, grasslands and wetlands. Conserving lands and waters under threat of development provides immediate greenhouse gas reductions, protects irreplaceable carbons stores, and advances Canada’s biodiversity goal to protect 30% of its lands, waters and ocean by 2030. Protecting these lands before they emit greenhouse gases is imperative in Canada to reach our climate goals.

To protect the livelihoods of foresters, farmers, ranchers and others, the study applied social safeguards in estimating the mitigation potential for NCS. For example, when evaluating the forestry pathways, the study assumed logging would continue at 90% of historical levels. The study also didn’t take productive agricultural lands out of use. Nor is there any double-counting: If the study estimated the mitigation potential of, say, cover crops on particular agricultural land, it didn’t also tally up how much greenhouse gas emissions could be sequestered through grassland restoration on that same land.

These social, economic and environmental safeguards, plus the new analysis of albedo, mean that the key result of this study—78 Mt annually in 2030—is a conservative estimate of nature’s potential in Canada. With this study in hand, decisionmakers can be sure they are equipped with reliable data and realistic expectations as they advance policy and investments.

Exploring Pathways

The Carbon Mapper tool demonstrates the contributions that the country and provinces can make toward mitigating climate change through natural climate solution. In the national view, the tool ranks provinces based on their mitigation potential; adjust the carbon price for each pathway to see how it affects provincial rankings and overall potential across the country. Select the province view to see how the different pathways perform in individual states.

These results build on studies led by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) showing the potential of NCS in the U.S. and worldwide—where nature could mitigate more than a third of the emissions needed to hit global targets by 2030. And like the previous studies, the Canadian study reinforced an important message about NCS: While nature is only part of the solution, many of these nature-based solutions can implemented today and at a relatively low cost compared with other mitigation strategies.

And the benefits of NCS radiate far beyond reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Protecting wetlands not only keeps carbon locked in soils and plant matter, but it also provides clean water, reduces flooding and provides valuable habitat for wildlife, including many endangered species. Deploying agricultural solutions can save farmers operating costs and provide alternative revenue options. Setting aside old-growth forests in active timber management, supports biodiversity.

Quote

While nature is only part of the solution, many of these nature-based solutions can implemented today and at a relatively low cost compared with other mitigation strategies.

Communities benefit from NCS, too, and in Canada—where 90% of lands are public lands that overlap with Indigenous territories—Indigenous leadership is vital to accelerating NCS. In places such as the Great Bear Rainforest, where TNC started working almost two decades ago, First Nations have established protected areas, trained guardians who monitor their traditional lands and waters, and started carbon market projects to raise revenue from the greenhouse gasses they’re keeping locked in their forests. In our experience, science and Indigenous knowledge are mutually reinforcing, building a solid foundation for climate action.

Canada’s example is exceptional in some regards, given our large land area and relatively small population. And like other countries, Canada has a lot of work to do in transitioning to clean energy and rapidly cutting fossil fuel pollution. But even so, this study shows just what a powerful tool nature can be for accelerating climate action, especially when it’s embraced by political leadership. We’ve got the political will, and now we’ve got the science to propel us forward.

Our Goals for 2030

Our planet faces the interconnected crises of rapid climate change and biodiversity loss.

the time for action is nowGlobal Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.