Restoring Alabama Rivers

Jason Throneberry, a TNC director for freshwater, talks endangered Alabama sturgeon, fish cannons and trying to save fish species he's never seen.

Interview by Matt Jenkins | Photographs by Cary Norton | Issue 1, 2024

Alabama has some of the most diverse fresh water in the United States. But dams have blocked the migrations of some fish on the state’s iconic Alabama River for decades. Jason Throneberry, the director of freshwater programs for The Nature Conservancy in Alabama, tells how a major partnership is trying to change that by building bypass channels for endangered Alabama sturgeon and other fish. “Bypass channels are, at the very least, a lifeline to those species,” says Throneberry. “This is a long game, and keeping that forward momentum is good.”

Matt Jenkins: How did you get into fisheries work?

Jason Throneberry: I grew up in south central Arkansas, and there are some pretty iconic rivers there: The White River, the Mississippi and the Arkansas all come together in the Gulf Coastal Plain. I spent a lot of time hunting and fishing and running around the rivers, and my wife and I were whitewater raft guides for 10 years. We’re river people.

MJ: You had a pretty significant shift in your own thinking about species protection and restoration that ultimately led you to TNC. Tell us about that.

JT: I worked for the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission for nine years and went all over the state looking at imperiled aquatic organisms, from cave snails to cave fish, to darters in big rivers, to alligator gar, whatever. I gradually realized that we can manage these species individually, but we really have to work at watershed scale. If we’re going to help these species persist, then we really have to look at the whole picture.

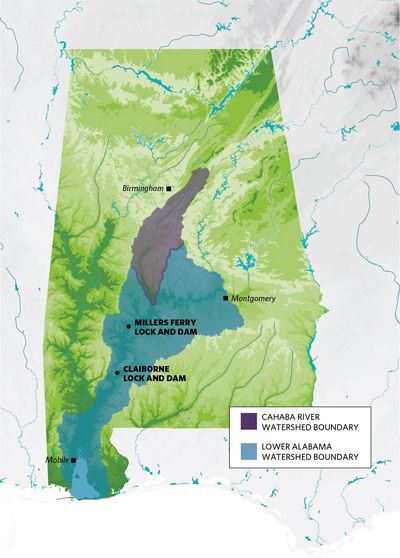

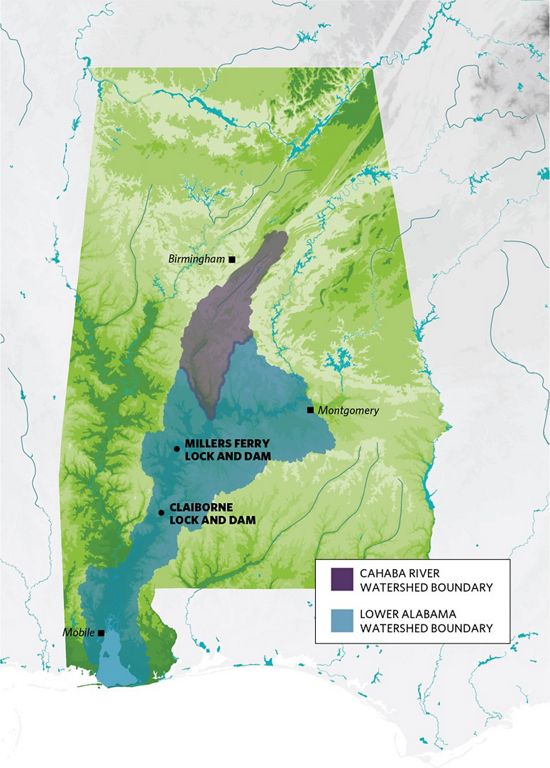

MJ: Now a major focus for you is a $160-million program with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to build bypass channels around two dams on the Alabama River. A lot of animals depend on a free-flowing Alabama River: sturgeon, paddlefish, mussels, mullet, skipjack herring and striped bass. What were fish migrations like historically, and how has that changed since the dams were constructed?

JT: We know that pre-dams, the migratory fish runs were just amazing. You had [endangered] Alabama sturgeon and [threatened] gulf sturgeon bumping all the way up against the Appalachian Mountains, trying to get up into the Appalachian portion of these rivers.

That doesn’t happen anymore, because these fish can’t do their thing. Not only because there’s a dam there, but you have changed a flowing, riverine ecosystem into a series of reservoirs. There’s no flow variation; there aren’t the big flood pulses anymore. You’ve lost all that.

MJ: How urgent is this effort? You mentioned that the elephant ear mussel is being kept alive only through artificial propagation, and there are big questions about how many Alabama sturgeon are left.

JT: Our research partners have been telling us, “Hey, we don’t know how many more years this population can hang on—or if it’s still there.” If we’re going to do something, the time is now.

So you’re two years into a joint feasibility study with the Corps of Engineers—walk us through the process. We started out the feasibility study with around 26 alternatives—everything from full dam removal to bypass channels to fish cannons to doing nothing.

MJ: Wait—“fish cannons”?

JT: Yeah, so they shoot salmon out of these big, huge water cannons to get them over the dam. It’s crazy, dude.

Anyway, most of the fish passage [work] that’s been done in the U.S. has been done out West. So it’s very specific to salmon, trout—really strong swimmers. You’ve seen trout runs—they’re just flying through the air. We don’t have those fish. So most of the alternatives were scratched from the get-go.

At the end of all that, the Corps of Engineers and TNC agreed that natural bypass channels were the best alternative, because they offer us way more opportunity to mimic what’s natural.

MJ: How does this all play into your own shift toward taking more of a whole-system perspective?

JT: The whole purpose of this project is to get fish around those dams. But in an even bigger sense, it is to ecologically reconnect the Gulf of Mexico to the Appalachian Mountains.

We’re not only working to reconnect the Alabama River up through the Cahaba River [farther upstream], but we’re working to make sure all that historic habitat that these fish need is still there. So we’re working from top to bottom, from bottom to top.

We are currently acquiring land in the upper Mobile-Tensaw Delta, right below these two dams. It’s the second-most-intact delta ecosystem in North America. You’re talking thousands and thousands of acres of delta that’s still functioning. And [the land acquisition] is not only about making sure that the fish can get up and about, but we also want all those ecosystems to interact again and make sure that they can function the same or better than they have. We really want to make them resilient.

MJ: The federal government, through the Corps of Engineers, will implement the fish bypass project and contribute $105 million. But that leaves $56.4 million that still needs to be contributed to the project. How is TNC helping this effort?

JT: TNC has a proven track record of bringing multiple parties to the table for huge projects like this. If you just show a little initiative and kick-start things, people will get behind it—they know what’s right to do. There just has to be someone willing to carry the banner and lead the charge to find the needed funds for this project.

Quote: Jason Throneberry

I’m working for species I’ve never seen, I’ve never touched—but I have hope that they’re still there. You’re doing this on faith that we haven’t messed stuff up to the point that nothing is there.

MJ: Let’s talk about Alabama sturgeon—nobody’s actually caught or seen one in quite a while, right?

JT: Correct.

MJ: That has to be kind of wild: One of the species you’re working to save may or may not actually be out there.

JT: There have been [randomly sampled] DNA hits for both species of sturgeon within the river. But yeah: I’ve never seen a gulf sturgeon or an Alabama sturgeon.

I mean, never.

I’m working for species that I’ve never seen, I’ve never touched—but I have hope that they’re still there. You’re doing this on faith that we haven’t messed stuff up to the point that nothing is there. And yeah, the first time I get to see a sturgeon swim up the bypass channel is going to be a happy day.

MJ: Taking this all on has been a long-term effort. Have there been any moments on the river that keep you going?

JT: Last summer we were doing our habitat assessments, and we took my work boat from Selma all the way down to the mouth, where the Tombigbee and Alabama River meet.

One day we were out there, and I wasn’t really paying attention, just kind of cruising along, and fish started jumping. I shut the engine down, got the binoculars out, and they were all paddlefish. Not just one or two—like 300-plus fish, from 6-foot long all the way down to the little babies. It was one of the coolest experiences of my life.

About the Creators

Matt Jenkins is a writer and former Nature Conservancy magazine editor who has written for The New York Times, Smithsonian and other publications.

Cary Norton is a photographer based in Birmingham, Alabama. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Garden & Gun and other outlets.