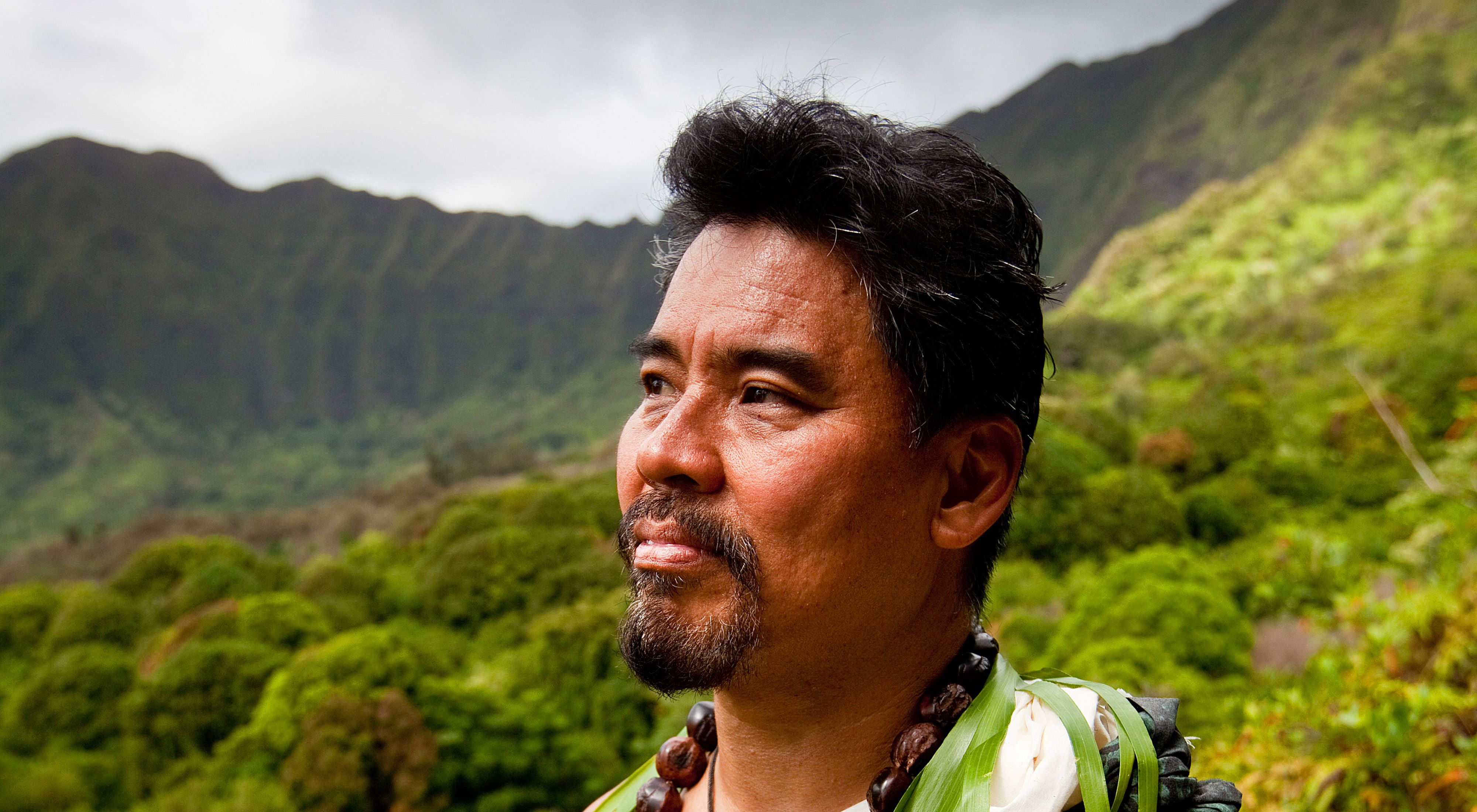

You’re a conservation biologist and an expert on Hawaii’s happy-faced spider. But much of your cultural cred comes from the fact that you speak Hawaiian fluently, teach Hawaiian chants and dance hula. That last bit surprised me—I didn’t know hula was a manly thing. Up until high school, I thought hula was just women dancing in dyed green skirts with coconut bras—the American idea of hula. But traditionally, hula was a largely male activity. Look at Captain Cook’s engravings of dancers. There aren’t any women. That was an eye-opener for me.

Your realization came when you were in high school in the ’70s during the “Hawaiian Renaissance”—a period when people were reviving ancient practices. Tell me more about what was happening then. There was this whole idea of rapprochement between Hawaiian culture and natural history. Our hiking-club advisers would take us up on trails and show us native plants and trees and birds. One mentor reveled in the Hawaiian aspects of the natural world. When you were hiking with him, you got the Hawaiian names of plants, learned the songs of the places.

Through those experiences you “fell under the spell” of the mountains. I hear you’re not nearly so enchanted by the sea. I am not at home in the ocean. I get seasick. I can’t snorkel for more than an hour. Whenever I kayak, I fully realize that there is a whole lifetime of enjoyment to be had in Hawaiian waters, but I’m not at all comfortable.

That’s unfortunate, given that you live on an island. How then can you say that when it comes to climate change, sea level rise is not your biggest worry? With sea-level rise, if you live on a low atoll you lose everything. If you live on a high island that goes up to nearly 14,000 feet, it is a relatively minor inconvenience—compared to other changes. Besides sea-level rise is happening, and people are going to adapt. At the highest high tide in Waikiki, lift up a manhole cover and the ocean is 4 inches below. The ocean slops out of the drains, which are crusted with salt. But humans are great at adapting. People talk about Waikiki being like Venice—abandon the lower floors and remain a tourist destination.

I find that kind of disturbing. So, if not sea-level rise, what disturbs you about climate change? Changes in weather patterns. There will be temperature and moisture combinations that don’t exist right now—mostly ones that are hotter and dryer. On Kauai, forest birds are relegated to the high plateau, free of mosquitoes. But mosquitoes move up with temperature changes. Or look at dry forests—they’re already tiny. If suddenly three-quarters of that forest becomes much too dry, it’s just gone.

You’re working with the Pacific Islands Climate Change Cooperative, a conservation alliance that funds projects to help land managers in the Pacific make informed decisions in the face of climate change. So what can you do for species that are in serious danger of losing habitat or dying out? We have embarked on a vulnerability assessment of every native plant in the Hawaiian Islands—about 1,000 species. We modeled their distribution and analyzed their moisture requirements. Then we looked at projections of where climate will change in 100 years. Now we can say: For this species, no habitat will exist; for this other species, the habitat will move up the mountain 300 feet, etc. Now we can say: If you are concerned about this plant, here’s what you can do.

What if you’re concerned about cultural changes? As a chant practitioner, you have said that historically, all natural processes were documented orally in Hawaii. And that chants survive because they are as evocative today as they were 500 years ago. Chants are the Hawaiian approach to conservation data. Like the book of Hawaiian proverbs. For example, one chant says that when the wiliwili tree is in bloom, the sharks are biting. Biologically, that means, in the season when the dry-forest tree blossoms profusely, the sharks are mating and extra-aggressive. That kind of information is all through Hawaiian chants. With global warming, you could conceivably have people creating new correlations, making new proverbs.